Editor's Note

*For previous entries in this series on cosmopolitan Christianity, see here and here.*

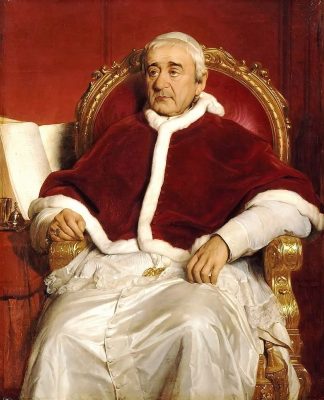

“Portrait du pape Grégoire XVI,” Paul Delaroche, 1844

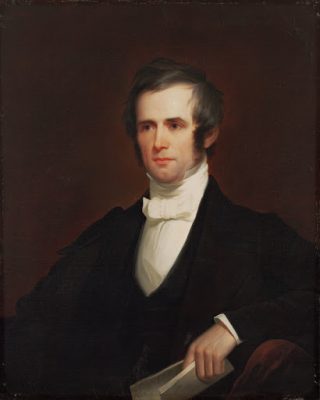

Bartolomeo Cappellari of Friulia ruled Rome as the Age of Revolutions drew to eclipse. His prodigious rise from country monk to head of the Holy See ran in tandem with the political upheaval of the Papal Sates. By the time 1845 dawned on the Eternal City, Pope Gregory XVI’s home was overrun with tourists and sin. Through the gritty streets strode new arrival Horace Bushnell. The Congregationalist minister, who had conquered his homesickness and embraced international travel, was eager for fresh religious experience. Giddy over the artistic glories of Milan and Florence, Bushnell turned to Rome with glee. “I seem to have breathed a finer atmosphere; and all my good feelings, if I have any, are invigorated,” he wrote after touring the Palazzo Pitti. “I feel conscious that my eye is forming or perfecting, and I know that it must be a benefit to me.”

The Connecticut clergyman, who reached Rome in early December 1845, timed his visit shrewdly. He chose to sample Catholicism as the season arced from Advent to Easter. Entering near the Basilica di San Giovanni a Porta Latina, Bushnell felt history whir by. Chariots and prayers, warmakers and peacemongers, had flown through where he stood. Traveling in the apostle Paul’s footsteps, Horace Bushnell found Rome to be a revelation. He was still weak from malarial fever, and at first the city proved to be a balm. He struggled to line up what he had read of ancient church history with what he now lived. He looked for ways into understanding the interior life of Catholicism, seeking out ideas and artifacts that rose above the “religious superstition” that he so often saw on display.

“The Transfiguration,” Raphael, 1516-1520, Vatican Museums

Like many visitors, Bushnell magnetized to the great artworks and worship aesthetics. Two paintings in particular appealed to him: Raphael’s Transfiguration (1516-1520) and Domenichino’s Communion of St. Jerome (1614). They hung, facing, in the Vatican. Raphael’s depiction was masterful but it lacked a godly unity, he thought. Domenichino, meanwhile, had perfected a theme that Bushnell planned to investigate further: “The supernatural is here clothed in the natural, the spiritual in terms of physics.” He left Rome with “a new sense of the possible grandeur of human power, and, at the same time, of its certain vanity.” Worship aesthetics and art history triggered his next inner journey.

Bushnell’s intellectual timidity eroded with travel. Strikingly, his American perspective on matters of church and state in Europe anticipated the revolutions of 1848, revealing his own muted stirrings of political reform. Bushnell’s critique of religious life in the “patchwork” of Catholic and Protestant cantons bisecting Switzerland was especially harsh. He deplored the impoverished existence of Calvin’s descendants as one where most people lived “not under the law but below it.” Once back in London, Bushnell made good use of his fleeting time abroad. He spent the spring of 1846 connecting with prominent Protestants and preaching to curious crowds. He printed a series of articles on the Oregon boundary dispute then inflaming American and British citizens alike. His many meetings with Christian Alliance members ultimately convinced him that Christian union was “visionary and unpractical,” a scheme far “too high for the whit of man” and far too weighty in erasing denominational markers of religious identity. The Alliance’s efforts, he concluded, would “make such a sea of good feeling that all sects will cast overboard their peculiarities, and run themselves into the same mould.”

By far, the most tangible legacy of Bushnell’s trip was his Letter to His Holiness, Pope Gregory XVI, a lengthy critique of the Roman Catholic Church and corruption. Bushnell labored over the piece throughout March, refining his arguments on papal oppression. The mini-manifesto saw publication in London on 2 April 1846. “It is a little too long, and perhaps a little too hard on the old gentleman,” Horace Bushnell reflected of his “remonstrance.” Rome agreed. Gregory XVI swiftly banned the American’s Letter. But readers continued to flock to Bushnell’s cosmopolitan critique, curious about his views.

Horace Bushnell (1802-1876)

In his Letter, Bushnell excoriated the suppression of Protestant practice in Italy and condemned Pope Gregory’s luxurious lifestyle in contrast to his people’s relative poverty. By subverting the duties of Christian character, Bushnell alleged, the elderly pope had enshrouded society and commerce in a nexus of secret partnerships that rotted the people’s spiritual health. Since his ascension in 1831, Gregory’s strict oversight of press, education, and industry made him into a petty king whose actions shamed the Christianity that he purported to represent—or so the Connecticut clergyman alleged. Even for Bushnell, the Letter was a surprisingly hard-edged rant. He charged Gregory with practicing a virulently anti-intellectual form of Catholicism, a tyrannical mixture of pageantry, superstition, and sacred relics that spurred fear rather than honest devotion.

Finally, the American pastor expanded on the danger of anti-intellectualism spreading among the world’s clergy. What, Bushnell prodded Gregory, would St. Peter make of such a successor? “Well was it for the occasion that he was not really there; else possibly, we might have had some demonstrations of the human Peter as well as of the saint,” he wrote. For, “when [Peter] saw the multitude wearing out the toe of his image by their idolatrous salutations, the old sword that cut off the ear…would…have been heard clashing thick upon the demolished head of his representative.” Widely circulated in Europe and at home, Bushnell’s Letter articulated what became a familiar set of American Protestant arguments against “Romish” oversight and Catholic worship habits. Horace Bushnell had begun to experiment with a powerful new voice for American Protestants, and drawn Catholics into the conversation through his bruising critique. With all of this whirling through his mind, Bushnell booked his return trip to Hartford. He had a new project at hand, one where he would emphasize the need to discover the “seeds of holy principle” hidden within. In the Vatican’s shadow, Horace Bushnell began his course of Christian Nurture.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Excellent, Sara! Thanks for this. I’m looking forward to your next post on Bushnell. – TL