Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

This post examines some of the texts included in Volume II, Part Three: To Extend Democracy and to Formulate the Modern. Here are all the texts included in this section:

Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939)

David E. Lilienthal, selection from TVA: Democracy on the March (1944)

Gunnar Myrdal, selection from An American Dilemma (1944)

Renhold Niebuhr, selection from The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (1944)

James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel” (1949)

Erik H. Erikson, selection from Childhood and Society (1950)

George F. Kennan, selection from American Diplomacy, 1900-1950 (1951)

Whittaker Chambers, selection from Witness (1952)

Perry Miller, “Errand into the Wilderness” (1952)

Hannah Arendt, “Ideology and Terror” (1953)

J. Robert Oppenheimer, “The Sciences and Man’s Community” (1954)

Norbert Wiener, “Men, Machines, and the World About” (1954)

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Loving Your Enemies” (1957)

John Rawls, “Justice as Fairness” (1958)

Peter F. Drucker, “Innovation–The New Conservatism?” (1959)

John Courtney Murray, selection from We Hold These Truths (1960)

W.W. Rostow, selection from The Stages of Economic Growth (1960)

Lionel Trilling, “On the Teaching of Modern Literature” (1961)

Milton Friedman, selection from Capitalism and Freedom (1962)

Ayn Rand, “Man’s Rights” (1963)

The American Century is over, in case you hadn’t noticed. The historical problem at this point is simply one of periodization – and I would date the end of the long American Century to November 2016. (Not sure where I’d date the start – maybe the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act). What will replace the WWII-Cold War-Globalization world order is still up for grabs, though my surmise (not a prediction – historians don’t make predictions) is that we’re now living in the Chinese Century. But history – history being the choices that people have made within the limiting conditions they inherit – is full of surprises.

Earth science as a field of inquiry offers a more reliably nomothetic measure of what awaits the world: global warming, rising sea levels, widespread famine. Of course, one massive volcanic eruption – say, the Yellowstone caldera – or one bullseye meteor strike could change the calculus there. Still, if things go the way they are going, we can put a closing bracket around America’s recognized leadership in international affairs.

Some people think that’s just fine; I do not. But it is ironic, and I prefer my history in the ironic mode. Well, not my history. These things are only supposed happen to other people’s countries, you know, not one’s own. That’s the (usually) unspoken expectation of Americans; that’s how we knew it was our century

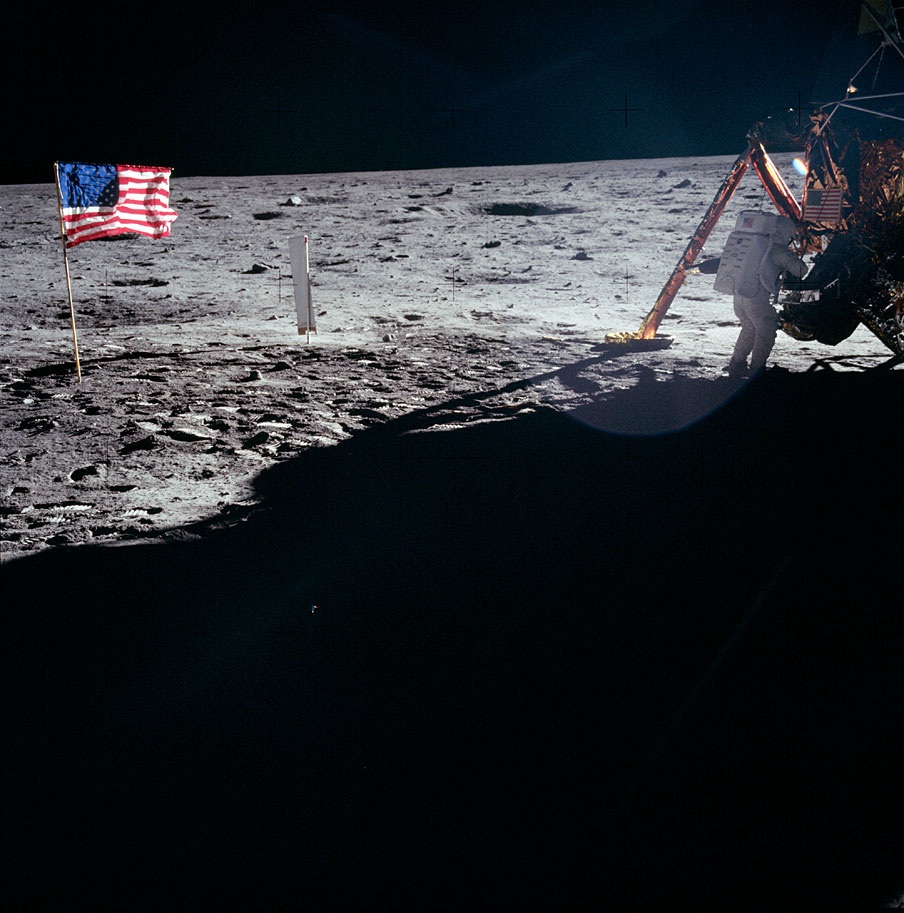

Armstrong on the Moon (courtesy of nasa.gov)

Interestingly, Henry Luce’s 1941 editorial essay, “The American Century,” is not one of the selections in this section of Hollinger and Capper. I hope they will include it in future editions, because its hope and its hubris about America’s place on the world stage will, I suspect, seem increasingly strange to students’ ears.

To witness the close of an era is strange – to be of the generation that grew up in the world as it was before and to realize that one will perhaps live (one hopes, or fears) to see the basic shape of the world yet to come. I was born just a few months before man set foot on the moon – arguably the zenith of the American Century (the moon landing, I mean). The lunar landing happened 49 years ago this week. That’s one small step for a man, and one giant leap for mankind…

The whole world was watching. The whole world was watching.

There are no excerpts from the Port Huron statement in this section either. So pardon me while I say what before I would have found unthinkable: Clement Greenberg (or Lionel Trilling) can go, to make room for Henry Luce – an instantiation of kitsch replacing avant-garde. And the John Rawls selection from this section can go as well, for we come across later Rawls in the next section. Let the idealists of Port Huron speak in this section, so that students hear what students thought was possible in the world they had inherited, in that American Century.

Here’s who can’t go, who mustn’t go: Reinhold Niebuhr and George Kennan.

I am too tired to make the case for Niebuhr here, beyond pointing out that the millennia-long contest between Pelagianism and Augustinianism has had its clear expressions in American thought of every era. Thus, for this era, Niebuhr the Augustinian should be read alongside the Port Huron Statement, as Pelagian as the day is long.

And I will let George Kennan make the case for himself:

…the American concept of world law ignores those means of international offense—those means of the projection of power and coercion over other peoples—which by-pass institutional forms entirely or even exploit them against themselves: such things as ideological attack, intimidation, penetration, and disguised seizure of the institutional paraphernalia of national sovereignty. It ignores, in other words, the device of the puppet state and the set of techniques by which states can be converted into puppets with no formal violation of, or challenge to, the outward attributes of their sovereignty and their independence.

Kennan was talking here about Other Peoples’ Problems, trying to explain to Americans why “the satellite countries of eastern Europe” were disenchanted with the United Nations. But it can’t happen here, right?

George Kennan thought it could:

In any case, I am frank to say that I think there is no more dangerous delusion, none that has done us a greater disservice in the past or that threatens to do us a greater disservice in the future, than the concept of total victory.

Imagine having the hubris to declare the end of history, and ourselves the victors.

Those were the days, and they are no more, and perhaps that’s for the best in the end. But the end is a ways off yet, hidden behind the bend of time before us.

As my grandmother used to say, It’s a long road that has no turning.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I’m currently finishing up a book on Luce’s editorial, and I agree it needs to be in any intellectual history volume. Although there’s a good argument to be made that the American Century, as Luce envisioned it, never really had a chance. Andrew Preston recently pointed me to this book on the early exit of the AC: https://www.amazon.com/Violent-American-Century-Terror-Dispatch/dp/1608467236

Professor Burnett,

Wow! Really? November 2016? I am curious why, you, of all people would chose that date for the end of the American Century.

The contest was two years ago. Your side lost. It’s time to let it go and move on. It’s not healthy.

Like many long suffering people in the upper Midwest, I must confess that as I watched the television I felt a certain amount of glee when I saw the horror on the faces of smug San Franciscans who believen they were entitled to victory saw a sudden incomprehensible defeat. I enjoyed watching the crestfallen visages of the Hollywood elites. How could a promising lead disappear. But I especially found the images of women crying inconsolably in Cleveland, to be sublime. I only wish that my feminist Grandmother could have been alive to see it. Grandma would have loved to see the 2016 Cubs win the World Series.

I’m not sure what you mean by my “side,” and I’m not sure whose side you think I’m on. I am a liberal, and I am a Republican — have been all my life. Now, I recently learned that, because I voted in the Democratic primary in Texas in 2016 (TX is an open-primary state), my party affiliation is now technically Democratic. You are affiliated with whatever party’s primary you vote in here. In 2016, I voted in the Democratic primary for the first time in my life. I had voted D in the general in 2008 and 2012, and in Nov. 2016, I voted for the Democratic candidate for the third time in a row.

Frankly, it would not have mattered to me who the Democratic candidate was — it was plainly visible to me then, as it is now, that Donald Trump was a white supremacist, a white nationalist, a violent misogynist, a shady businessman with financial dealings he insisted on hiding, a retrograde racist, a complete ignoramus, a demagogue, and an aspiring authoritarian who was quite obviously under the sway of a foreign dictator. So yes — if by my “side” you mean the voters of this country who oppose all those things, we certainly did lose. How sad that you would find this satisfying.

As to periodization, I date 2016 as the end of the American Century because in terms of foreign policy and practice this presidency has been characterized by isolationism, appeasement to a hostile foreign power, the deliberate kneecapping or destruction of various military and trade alliances which America once led / supported as a matter of policy. Meanwhile, the majority party in Congress, an equal branch of government, is so compromised by its own kleptomania, or so terrified of kompromat, that they are sitting on their hands while the kleptokakistocracy in power plunders the public good with a shamelessness that would make U.S. Grant’s cabinet members or the Harding administration blush in horror.

Now, I can’t speak for “smug San Franciscans,” since I grew up in the San Joaquin Valley, the poorest, most under-resourced, under-educated, under-served region of California. One of the reasons my parents moved to TX to live near me in their old age is that the nearest medical specialists who could address their needs were at Stanford, a two hour drive from their home. They voted for Trump, “for economic reasons,” my mom says. But so far they haven’t expressed any regret for their vote, a fact which I find utterly incomprehensible. Every day this puppet of a foreign power sits in the White House is a walking nightmare for me.

Your last remark, about taking special pleasure in “the women crying inconsolably in Cleveland,” is bizarre. I don’t quite know what to make of it, to be honest, beyond the obvious observation that it’s sexist and also probably ageist. If you meant your comments as parodic, sarcastic, or satiric, you missed the mark…badly.

I really don’t have much more to say to you, ever.

L.D.,

Interesting post. Apologies for the length of this comment, but having written it I’m too lazy to shorten it. I’m not sure the periodization of when the American Century began or ended is resolvable (or, perhaps, that pressing). The Bacevich-edited volume The Short American Century: A Postmortem, which I referenced in my guest post here last February (Feb. 9, to be exact) is one relevant work, but I’m not sure any particular end-date for the American Century, “long” or “short,” will command wide agreement.

One can detect, however, trends or waves in how U.S. or U.S.-based writers (mainly academics, in the nature of these things) and others have thought about the position of the U.S. in the world in recent decades (and of course going all the way back to the early republic). After the end of the Vietnam War, there was a feeling that U.S. exceptionalism had run its course and that the country should embrace or at least reconcile itself to the status of “an ordinary country” (see R. Rosecrance, ed., America as an Ordinary Country: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Future, 1976). But this discussion remained largely confined to the academy, probably; few or no politicians felt they could use the phrase “ordinary country” and make it sound like something positive.

Paul Kennedy’s 1987 bestseller The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, with its not-so-implicit message that the U.S.’s “imperial overstretch” threatened to hasten its relative decline vis-a-vis rising powers, esp. China, struck a nerve, eliciting rejoinders. But the combination of Reagan’s rhetoric, the dissolution of the USSR and end of the Cold War, and the First Gulf War produced a period of triumphalism. Symbolically at least, 9/11 probably marked the end of that. And the unsatisfactory (to put it mildly) course of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, plus other aspects of the “war on terror,” coupled with shifts in the global balance of power that would have occurred anyway because they were being driven largely by demographic and economic trends, should have led some people to blow the dust off Kennedy’s book and re-examine his argument.

From this slightly longer perspective, the more contentious questions raised by Trump’s election have to do not with “the end of the American Century,” which I think happened a while ago, but with the (alleged) end or weakening of the U.S.-led “liberal international order.” Here there is disagreement (even within the spectrum of so-called mainstream views). There are those who think that the withdrawals from the Trans-Pacific trade agreement, the Paris Climate Accord, and the Iran nuclear deal, plus the cozying up to Putin (on the level of rhetoric and perception, at least) threaten to undermine the “liberal order,” whereas others think that order’s achievements have been exaggerated and that the U.S. “should limit its efforts to ensuring sufficient order abroad to allow it to concentrate on reconstructing a viable liberal democracy at home” (G. Allison writing in Foreign Affairs, July/Aug 2018).

Put in this general way, the argument is not really new, but Trump’s election has sharpened it. George W. Bush, it may be worth recalling, scuttled the ABM agreement with Russia, dissed the Tokyo protocol on climate change, and refused to let the U.S. participate in the then-new Int’l Criminal Court. These and other moves (followed by the invasion of Iraq and the split it led to with major European allies) provoked a lot of criticism about the G.W. Bush admin’s retreat from and devaluing of multilateralism, but I don’t recall it provoking the kind of handwringing over the end of the liberal int’l order that Trump has provoked. This suggests that, even more than his substantive actions, it is Trump’s erratic verbal behavior and general lack of coherence in policy, coupled with a soft spot for Putin (whether because Putin has compromising info on him or for other reasons), that are driving much of the concern.

Beneath the rhetoric and the public dissing of allies, however, the deployment of U.S. military forces in the world has not changed much. Indeed, Trump, compared to the previous administration, has engaged in more drone strikes and counter-terror operations in places like Somalia, he has loosened restrictions on the U.S. anti-ISIS bombing campaigns in Iraq and Syria, resulting in more killing of civilians, and he has let Saudi Arabia use U.S.-made bombs in Yemen, not only leading to a lot of civilian deaths but helping cause a humanitarian catastrophe, with a cholera epidemic and the country on the brink of a mass famine.

“… but having written it I’m too lazy to shorten it.”

Now you know the process behind every single one of my blog posts!

More seriously…

When teaching the survey, I generally periodize the late 20th century as follows:

end of the Cold War – ’91

America and the age of globalization – ’91-2000 [or, “from the world wide web to the War on Terror”]

the War on Terror” – 2001-present

For Americanists, I would periodize “the long 20th century” as follows: 1877 – 2001 if looking primarily at domestic US history, 1898 – 2001 if looking primarily at “US and the world”

However, I would periodize “the American century” — the age of American emergence and then dominance as the leading liberal democracy — from 1917 – 2016.

I had not seen Susan Glasser’s New Yorker piece on the post-Helsinki fallout for U.S. foreign relations before I wrote this post, but I think it’s really outstanding, and sums up why I think 2016 marks the end of a longer era. You can read it here: “No Way to Run a Superpower”: The Trump-Putin Summit and the Death of American Foreign Policy

As someone noted on Twitter following the Helsinki press conference, “I’m looking forward to changing my course title from ‘Introduction to American Foreign Relations’ to ‘Conclusion to American Foreign Relations.'”

Obviously, the arc of history is long, and the longer view one takes, the more these seeming turning points smooth out into minor divots and bumps. However, the acquiescence of the Republican leadership in Congress to a string of foreign policy acts / decisions which are quite obviously not in the interest of the U.S.’s traditional allies / NATO (never mind the U.S!) but clearly in the interest of Russia is absolutely astonishing. This is a liquidation sale — every principle and commitment must go!

It’s truly disheartening.

Thanks for the link to Susan Glasser. (And on the periodizations: fair enough.)

This piece from about a week ago by J. Stacey, who is not at all a fan of Trump, argues among other things that “European allies [of the U.S.] are in fact partly to blame [via their defense-spending and trade policies] for the rise of nationalist politics in the U.S. and the arrival of Donald Trump.” Which doesn’t excuse Trump, of course, but is an interesting point.