Editor's Note

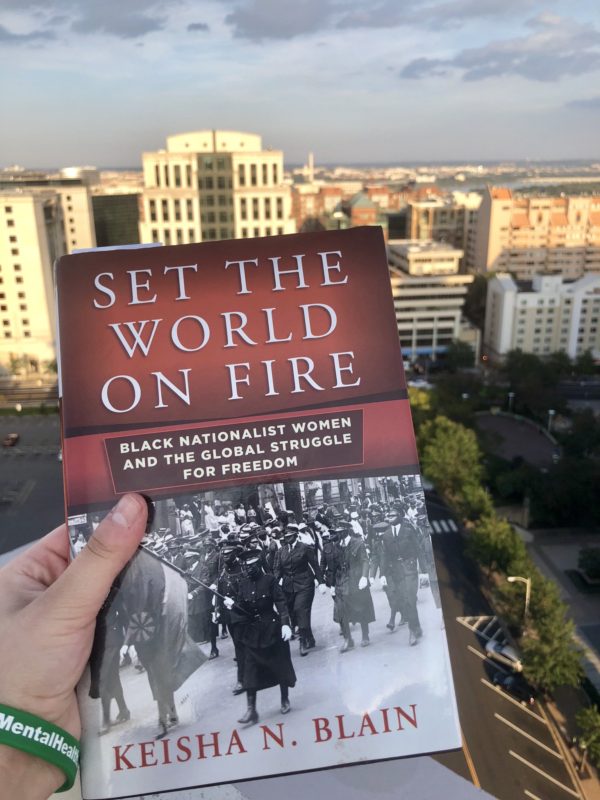

This post is part of a two week Salon on Dr. Blain’s book Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle For Freedom.

Historians conduct primary research to illuminate narratives that inform collective understanding of the past, as well as how that past informs the present. To accomplish this, historians must consider a diverse, wide range of perspectives. Most scholars likely think it difficult to consider minority, international, and even illiterate persons simultaneously. However, a recent firebrand has accomplished just that: Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom by Keisha N. Blain examines black nationalist women’s national and global politics from the 1920s through the 1960s.

Black perspectives matter, especially in writing history. Blain defines black nationalism as the “political view that people of African descent constitute a separate group or nationality on the basis of their distinct culture, shared history, and experiences [and therefore] advocated pan-African unity, African redemption from European colonization, racial separatism, black pride, political self-determination, and economic self-sufficiency” (3). While British colonialism continued in Africa, the United States exercised “territorial, economic, and political control over people of color” (5). White colonialism inflicted this situation on the historical figures in Blain’s book, and they became activists and intellectuals in the process of addressing their realities. Central to Blain’s narrative are the perspectives of women: Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, Ethel Waddell, Celia Jane Allen, Ethel Collins, Amy Jacques Garvey, Amy Ashwood Garvey, Maymie Leona and Turpeau De Mena. These women revised what Blain calls the “masculinist vision of black liberation” to add women.

Writing working-class histories and incorporating international perspectives can each be challenging due to source work. Women in poverty leave sources that are challenging to uncover, if at all. Global perspectives likewise might seem out of reach due to language barriers. However, Set the World on Fire accomplishes both. The book “highlights black nationalist women’s political organizing in the U.S. North, Midwest, and Jim Crow South,” as well as “their transnational work and collaborations with activists in North America, Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean” (3). As for source work beyond paper trails, Blain draws on historical newspapers to uncover the activities of impoverished, working-class, and at times illiterate black women (78-81). She takes these women seriously as intellectuals in their own right. Set the World on Fire epitomizes where American intellectual history should go. Transnational histories, the ideas of people who could not leave paper trails, adding people of color, women, and especially women of color represent the makings of a more sophisticated scholarship of ideas in action.

0