Editor's Note

This is the first in a series of guest posts by Andrew Klumpp, a PhD candidate in American religious history at Southern Methodist University. His research investigates rising rural-urban tensions in the nineteenth-century Midwest, focusing on rural understandings of religious liberty, racial strife, and reform movements. His work has been supported by grants from the State Historical Society of Iowa, the Van Raalte Institute, and the Joint Archives of Holland and has appeared in Methodist History and the 2016 volume The Bible in Political Debate. He also currently serves as the associate general editor of the Historical Series of the Reformed Church in America.

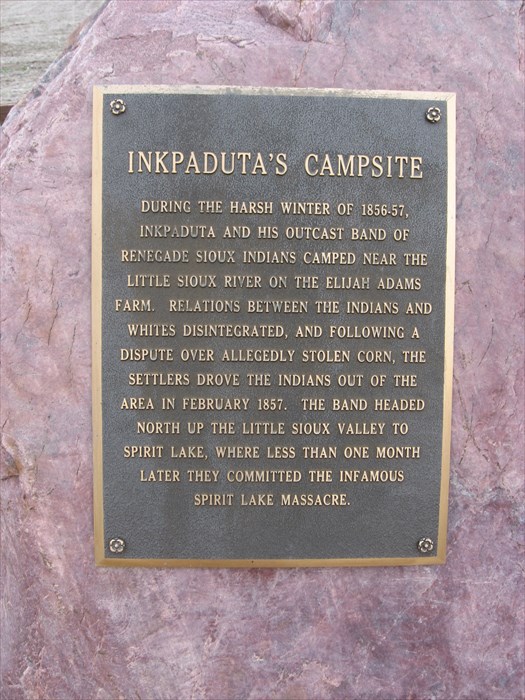

As a child growing up in rural Iowa, I occasionally heard frightening tales about a man named Inkpaduta, normally dramatically told around a campfire by one of my uncles. Hovering around a fire in the woods along the Little Sioux River in Northwest Iowa in the early 1990s, my uncle told a child-friendly, but still terrifying, story about a Sioux warrior and chief named Inkpaduta, who, once upon a time, had traveled the river looking for children to attack. He had refused to leave his tribal lands and consistently evaded capture by the government. In my uncle’s telling, nearly 150 years after the last Sioux left the area, he continued travel along the Little Sioux River.

Only portions of my uncle’s story were true and, in actuality, the story was far more complicated. Inkpaduta really led a small band of Sioux who lived in the Sioux River Valley in the early and mid-1800s. He did carry out a brutal attack on white settlers during the bitter winter of 1857. It became known as the Spirit Lake Massacre and left 32 people dead, including many children and at least one newborn. Over the next two decades, he never repented and effectively avoided being capture by the U.S. government. He fought alongside famous Sioux leaders like Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull in the wars that took place in the West during the 1860s but, unlike most of his compatriots, he survived every battle and never surrendered, choosing instead to move permanently to Canada, dying of pneumonia in the late 1870s rather than at the hand of a white aggressor.[1]

After the Spirit Lake Massacre, Inkpaduta gained a reputation as a bogeyman, lurking behind every clash between white settlers and the Sioux. Rumors that he had returned to Iowa or Minnesota from the Dakota Territory or Canada could throw the small white communities into a panic, causing some settlers to make a beeline to the nearest fort and others to hole up for days to protect against an impending assault.[2]

The idea of Inkpaduta took on a life of its own. His reputation cast him as an unredeemable figure. The brutality of the Spirit Lake Massacre—the details of which were prudently left out of the children’s campfire version—defined him in the minds of white settlers on plains. Other Sioux leaders carried out larger massacres and fought just as fiercely against the incursions of the U.S. government. Many are now memorialized on stamps, in history books or, in Crazy Horse’s case, in a monument carved into a mountain.

The idea of Inkpaduta took on a life of its own. His reputation cast him as an unredeemable figure. The brutality of the Spirit Lake Massacre—the details of which were prudently left out of the children’s campfire version—defined him in the minds of white settlers on plains. Other Sioux leaders carried out larger massacres and fought just as fiercely against the incursions of the U.S. government. Many are now memorialized on stamps, in history books or, in Crazy Horse’s case, in a monument carved into a mountain.

Not Inkpaduta. He fought relentlessly against the U.S. government, participated in the major battles of the Sioux’s wars with the U.S. government and, according to some accounts, his son even slayed George Custer in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.[3] Inkpaduta never surrendered. His ability to survive and unrepentant resilience made him different from his compatriots and, ultimately, proved to be the most frightening element of his story, shaping both his reputation at the time and, ultimately, his legacy.

The history of Inkpaduta’s reputation as a skulking, evasive and violent Sioux chief reveals that his legend consistently struck fear into the hearts of whites. White settlers both in the past and in the present never presented Inkapuduta as “the noble savage.” In their estimation, he was wild and evil, undeserving of the respect of his white contemporaries. Later generations rarely feel even a tinge of guilt for having forced Inkpaduta off of the lands that his people had roamed for centuries. In the mid-1800s, the specter of his return could justify acts of distrust and violence against all Native Americans, not just the Sioux. The legend of his brutality came to demonstrate the unfitness of the Sioux to occupy the land—never mind that white settlers had perpetuated far more extensive massacres themselves as they progressed across the continent.

Inkpaduta is a complicated figure. I found myself disgusted reading accounts of the events of the Spirit Lake Massacre, particularly the methods used to murder the young children and infants. At the same time, I felt great empathy for him. The Sioux and, specifically, Inkpaduta had been frequently double crossed by whites who were forcing themselves onto Sioux lands. The Sioux had watched tribal leaders be betrayed and often murdered by whites and witnessed their own children starve to death due to overhunting by new settlers. Behind the legend, I found Inkpaduta to be a complicated and often sympathetic figure.

Several years after hearing my uncle’s campfire tales, my middle school class went on a field trip to a town with a population of approximately 300 people to learn about the early settlement of Northwest Iowa. While there we heard the story of Inkpaduta again, this time surrounded by the artifacts in a local museum. To be honest, it was really just a barn with an extensive collection of local history memorabilia—in rural Iowa though, that’s a museum. The story of Inkpaduta focused, predictably, on the Spirit Lake Massacre. The small community that we were visiting had been Inkpaduta’s first stop on his violent tour of the area. Though our guide didn’t try to frighten us by the prospect that the chief still roamed the Little Sioux River as my uncle had done, in his re-telling, like nearly all others, the Sioux warrior was an unqualified villain.

It leads me to wonder what something like the legend of Inkpaduta, especially when contrasted to his complicated life, means for the history of ideas and reputations, particularly in rural areas and in the history of the West. It’s hard to trace directly the history of an idea passed by word of mouth around campfires or in barns overflowing with local history ephemera. Yet, the simplistic and problematic idea of an undeserving, violent, and evil Sioux chief lingers over 160 years after the notorious massacre he led, striking fear into the hearts of children and undergirding mythologies of western settlement in much the same way it did in the wake of the actual attack.

__________

[1]Paul N. Beck. Inkpaduta: Dakota Leader (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008).

[2]Beck, 113-14, 117, 122.

[3]Beck, 138-39.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I was just at Spirit Lake last summer—for a family vacation and gathering. Now I’m wondering where on the lake the massacre occurred? We stayed in a rental property on the southern edge of East Lake Okoboji. But we rented a boat and traveled on both the East and West Lakes. Apparently boats are not allowed on Spirit Lake. I don’t recall reading or hearing about Inkpaduta while there, but family vacations are often a blur. My retention of things read in exhibits or in regional tour guides is, sadly, minimal. – TL

Hi Tim:

The massacre actually occurred in various places around Spirit Lake and both East and West Lake Okoboji. In concluded on Spirit Lake, thus the name. Inkpaduta’s band would approach a settler’s home requesting supplies and then kill the inhabitants before moving on to the next home. Since the snow was so deep and the weather so frigid, travel was limited and the massacre actually took place over a series of days. The first attack took place on the southern shores of East Lake Okoboji (likely near present-day Milford) and the final attack took place at a homestead on the southern shores of Spirit Lake several days later. We only know many of these details because one of the three women that the band took captive survived for several months before the U.S. provided supplies for the Sioux in exchange for her release. There are a few small memorials to the event in the city parks, but they are not particularly prominent.

Regarding boating on Spirit Lake, from what my family tells me, they had strict limits on boating last summer because of high water levels after an abundance of rain. If you return in the future when water levels are lower, hopefully you’d be able to boat on Spirit.

Thanks so much for the question!

AK