Editor's Note

For nearly two decades, I’ve taught an undergraduate Honors Course at the University of Oklahoma built around the readings in Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition. As part of LD Burnett’s series of posts rereading Hollinger & Capper, I’m doing a series of posts exploring what it’s like to teach the volumes in an undergraduate, honors setting. In my first post, I said a few general things about Perspectives on the American Experience: American Social Thought, the course (or actually courses) in which I use The American Intellectual Tradition. When I began this course, The American Intellectual Tradition was in its 3rd edition. Unless otherwise noted, I’ll be blogging about the most recent edition of the books, the 7th. In this ninth post in my series, I discuss teaching Volume II, Part Three, entitled “To Extend Democracy and to Formulate the Modern.” For more on Volume II, Part Three, see LD’s post on it. I’ll be blogging about a new section every two weeks as LD works her way through the book, though this particular post arrives a week late. In these posts, I am generally am not attempting to provide a comprehensive description of what I do with Hollinger & Capper in the classroom. Instead, I will usually be highlighting an aspect or two of my approach to each section. Please feel free to use the discussion thread for more general comments or questions about teaching this particular part of The American Intellectual Tradition.

Who knew that the American intellectual tradition could be so thrilling?

As LD Burnett notes in her post on this section, Henry Luce’s “The American Century” would fit well in Part Three of Volume II of The American Intellectual Experience. Luce’s essay was in earlier editions of AIT, most recently the 5th (2006), along with Henry Wallace’s “Century of the Common Man.” This traditional pairing of Luce and Wallace taught wonderfully.

Their absence from this volume, since 2011’s 6th edition, reflects a larger aspect of Part Three in its current version. Although the readings in it run from 1939 through 1963, Part Three is very much organized around the Cold War. Although there are certainly other contexts in which to read it, Clement Greenberg’s “Avant Garde and Kitsch” (1939), the earliest reading in Part Three, appears here as a kind of anticipation of Cold War liberalism from the pages of the still distinctly radical, but already strongly anti-Stalinist, Partisan Review. Two other readings in Part Three were published in 1944, but became much more salient in American thought after the War: Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma and Reinhold Niebuhr’s The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness. The only other text from before 1945 is the selection from David Lilienthal’s TVA: Democracy on the March. Though written in 1944, as its author and title suggest, it’s very much an expression of New Deal liberalism and feels a little out of place in Part III.

The Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II are a kind of watershed period for many of the issues that show up in Cold War garb in Part Three. But with the Great Depression and the New Deal oddly split between Parts Two and Three (as I discussed in my last post on Hollinger & Capper) and World War II and the wartime experience largely absent from Part III, they feel oddly underplayed in the 7th Edition.

None of which is to suggest that there’s much that I’d want to see cut from Part Three. So let’s move from noting what is not in this section of the volume and focus, instead, on what is in it.

Like Parts One and Two of Volume II, I spend three weeks on Part Three when I teach this material in my American Social Thought class. And, as with Parts One and Two, I divide the material across those three weeks thematically.

We start Part Three during the ninth week of class, immediately after Spring Break. That week we read:

Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939)

Erik H. Erikson, Selection from Childhood and Society (1950)

Robert Oppenheimer, “The Sciences and Man’s Community” (1954)

Norbert Wiener, “Men, Machines, and the World About” (1954)

W.W. Rostow, Selection from The Stages of Economic Growth (1960)

Lionel Trilling, “On the Teaching of Modern Literature” (1961)

In a sense, this week of material continues conversations that were important in Part Two. I think of it as, broadly speaking, built around the theme of modernity, which was the focus of the last week of material from Part Two. But this material from Part Three is additionally very much concerned with the relationship between science and society, which is also an important issue in Part Two. The Norbert Wiener essay, which is new to the 7th edition, is a particularly good addition in this regard.

My second week of material from Part Three raises some more novel issues:

David E. Lilienthal, Selection from TVA: Democracy on the March (1944)

Reinhold Niebuhr, Selection from The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (1944)

George F. Kennan, Selection from American Diplomacy, 1900-1950 (1951)

Whittaker Chambers, Selection from Witness (1952)

Hannah Arendt, “Ideology and Terror” (1953)

Milton Friedman, Selection from Capitalism and Freedom (1962)

Ayn Rand, “Man’s Rights” (1963)

These readings revolve around questions of democracy, totalitarianism, and America in the world. Niebuhr, Chambers, and Arendt, in very different ways, grapple with the challenge of totalitarianism and its relationship to democracy. Kennan suggests that this is the wrong frame within which to pursue American foreign policy. And Friedman and Rand offer two different versions of free market ideology that are opposed not only to Communism but also to the kind of liberalism endorsed by New Dealers like Lilienthal.

Between the 6th and 7th editions of The American Intellectual Tradition, Hollinger & Capper dropped Daniel Bell’s “The End of Ideology in the West” (1960). From a pedagogical perspective, I miss Bell’s essay much more than I miss Luce and Wallace, because “The End of Ideology” lends itself so nicely to being put in conversation with other readings in this volume. Bell and Arendt provided a fascinating contrast on the issue of ideology and its relationship to democracy. Chambers and Niebuhr could also be brought into this conversation. And, crucially, C. Wright Mills’s “Letter to the New Left,” which, as we will see, is still in Part Four, is very directly a response to Bell’s essay. (Oh well, so much for confining myself to what is in the 7th edition!)

My third and final week of material from Part Three includes the following readings:

Gunnar Myrdal, Selection from An American Dilemma (1944)

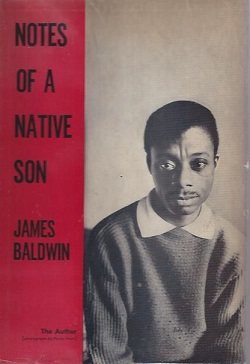

James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel” (1949)

Perry Miller, “Errand into the Wilderness” (1952)

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Loving Your Enemies” (1957)

John Rawls, “Justice as Fairness” (1958)

Peter F. Drucker, “Innovation – The New Conservatism?” (1959)

John Courtney Murray, Selection from We Hold These Truths (1960)

I emphasize two, interrelated issues when I teach this material. On the first day of the week, I focus on Myrdal, Baldwin, Miller, and Murray and their understandings of the place of race and religion in the American experience. On the second day of the week, I focus on King and Rawls as representatives of new forms of liberalism and Drucker as an attempt to formulate a new kind of conservatism, one which happens to contrast nicely with the Rand and Friedman readings from the previous week.

The Baldwin and King readings in this last week are new to the 7th edition. Through the 6th edition, Volume II included Baldwin’s “Many Thousands Gone” instead of “Everybody’s Protest Novel” and King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (in Part Four) rather than “Loving Your Enemies” (in Part Three).

Both of the two Baldwin essays present some pedagogical challenges, as each assumes a certain familiarity with a novel most of the students have not read – Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the case of “Everybody’s Protest Novel” and Native Son in the case of “Many Thousands Gone.” Both Baldwin essays were published in Notes of a Native Son (1955). Each is an extraordinary piece of writing. Both present key aspects of Baldwin’s early thought, including both his understanding of the place of the African American experience in the larger American experience and his critique of dominant modes of representing the African American experience. But if I had to choose between the two pieces, I’d go with “Many Thousands Gone” over “Everybody’s Protest Novel.”

Both of the two Baldwin essays present some pedagogical challenges, as each assumes a certain familiarity with a novel most of the students have not read – Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the case of “Everybody’s Protest Novel” and Native Son in the case of “Many Thousands Gone.” Both Baldwin essays were published in Notes of a Native Son (1955). Each is an extraordinary piece of writing. Both present key aspects of Baldwin’s early thought, including both his understanding of the place of the African American experience in the larger American experience and his critique of dominant modes of representing the African American experience. But if I had to choose between the two pieces, I’d go with “Many Thousands Gone” over “Everybody’s Protest Novel.”

The change in King essays is more complicated. “Loving Your Enemies” concerns very different things from “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” While “Letter” focuses on the issue civil disobedience and offers a profound, practical critique of self-described racial moderates, “Loving,” which began life as a sermon, shows King working at the intersection of theology and political theory. Race is much less an issue here than nonviolence and how one should think about one’s opponents in a revolutionary struggle. “Loving” is also a lot less familiar to my students. “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” is probably King’s second most read work today (though it is a rather distant second to the “I Have a Dream” speech). Unlike “Loving,” some of my students will inevitably have encountered it before. Overall, I very much like the addition of “Loving,” which enriches our conversations about liberalism and radicalism in mid-20th-century America. But I miss “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Perhaps King, like William James and Randolph Bourne, deserves two readings in this volume.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this reflection, Ben. I love hearing about your experiences with the different AIT editions. – TL