Editor's Note

This is the second part of a two-part essay written by Adolph Reed, Jr. The essay, based on a paper he gave at the University of New Mexico for their annual African American History Month celebration, explores recent debates about the uses–and utility–of Black history in both the academic and public spheres. Part one ran last week.

Interventions like the 1619 Project and Thirteentherism are darker expressions of the practice of attending to the past for allegorical purposes. They are extreme extensions of a disposition to abjure historical complexity out of commitment to producing accounts of unremitting brutalization and oppression of black people at the hands of “whites” or an abstract White Supremacy, which sometimes seem like oppression porn. This tendency militates against nuanced historical understanding, as in a moralizing inclination to reduce slavery and Jim Crow to what my historian son exasperatedly describes as “white people’s permanent sadistic camp” for blacks. He has noted also that in recent years undergraduates, both black and otherwise, take issue with description of slavery as a labor system, as though thus describing it makes light of slaves’ suffering and the moral opprobrium the institution merits, and resist considering whether it’s accurate as a historical characterization. Prof. Barbara Jeanne Fields has remarked similarly that much current discussion of slavery presumes that its point was to produce white supremacy, not cotton, cane, rice or indigo. She has also observed that, if racism were the cause and purpose of black slavery, a much simpler solution to racial aversion would have been simply to leave blacks an ocean away in Africa.

The punch line of these darker allegorical accounts is that nothing has ever improved black Americans’ circumstances meaningfully and that, moreover, efforts to make things better have only made blacks worse off. A bracing early encounter I had with this interpretive inclination came in the 1990s, when I was teaching a fairly large enrollment (I remember that because it was one of those courses in which I had to lecture from a stage) black politics course. My lecture was on the thirty years of contestation between Emancipation and the descent of the Jim Crow order, and I noted that the sharecrop system took shape as a compromise, albeit one that reflected the asymmetrical power of planters and tenant farmers, between the freedpeople’s desires to work on their own without immediate planter supervision and the landowners’ preference for instituting a labor system as close as they could get to slavery. My point was that to that extent, the sharecrop system, though hardly ideal, was something of an improvement for black southerners. An earnestly perplexed student raised her hand and noted that her professor, whom she named, in an African American Studies course had insisted that sharecropping, and the Jim Crow regime, were indeed worse than slavery for freedpeople. I was flummoxed, partly because of the constraining guild imperative to avoid criticizing or disparaging a colleague in front of students, but also because I couldn’t for the life of me understand what objective would justify imposing such a defeatist – and inaccurate – argument onto students. And it was one that hardly qualifies as inspirational or shows any regard for actual black people’s “agency,” which is another shibboleth of the history as allegory tendency.

Fast forward roughly two decades, and I had a similar encounter, but with an adult, presumably a credentialed historian, who unlike the undergrad, was fully committed to a version of that “nothing ever gets better for black people” narrative. On a 2015 panel at the Southern Historical Association convention, I gave a presentation on the bi-racial/interracial character (the distinction didn’t matter much before Plessy made racial segregation a central political flashpoint) of the late-nineteenth century Populist insurgency and discussed its violent suppression, including the vicious 1898 Democratic putsch against the twice-elected Populist-Republican-Fusion government in North Carolina. After the panel, which was organized in honor of SHA president Barbara Fields (by the way, it was after this panel when Prof. Fields and I had the discussion that led to her asking, with some enthusiasm, to see the too long for an article, too short for a book draft that eventually, in no small measure because of her support, became The South), a panel attendee approached to catechize me, with no trace of hostility, on the point that the real story of the defeat of Populism was the fact that white farmers and workers forsook alliance with blacks for the appeal of white supremacy. I allowed that that no doubt was part of the story but reminded her of the centrality of the campaign of rampant violence, fraud, outright theft, murder, and intimidation waged against insurgents, white and black, throughout the region, before and after 1892. Her response, cavalierly sloughing off my qualification, was, “Yes, there was that too, but the real explanation for the defeat was whites’ commitment to racism.”

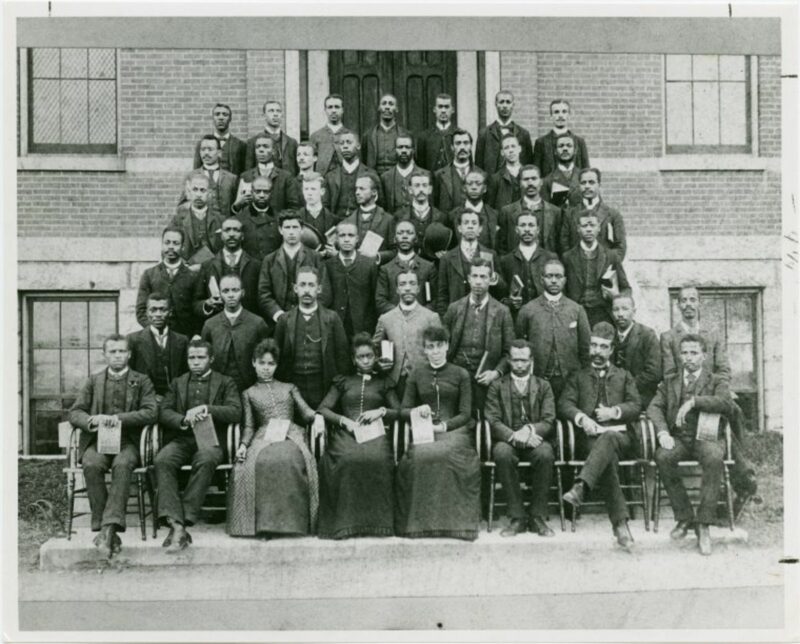

Fisk University Class of 1888

It would be interesting to reconstruct precisely how the history as allegory approach came to be dominated by the profoundly defeatist and race-reductionist “nothing has changed” narrative. For now, I want to underscore that the dark expression of the approach has become hegemonic; by the end of the 20-teens, as the broad popularity of 1619-ism and Thirteentherism, among other interpretive pathologies, indicates, it was the standard template even for the celebratory, inspirational/uplifting tale type: extraordinary black figures are now even more extraordinary because they rise from and at least momentarily overcome unrelenting suppression from all quarters, all the time by whites who seemingly exist to embody a sadistic White Supremacy, with the occasional “white ally” who seemingly exists to embody plausible deniability against the charge that this story racially demonizes whites.

Considering the shifting ideological environment within which the premises of African American history as allegory have evolved may offer clues to the rise of the “nothing has changed” perspective. Already in the 1980s black opinion-shaping strata in general emphasized projecting positive images about and for black Americans –presumably to counter their damage by racism and cultural pathology — as an important element of strategy for blacks’ advancement. Although few acknowledged it, this turn was an accommodation to the bipartisan national and local policy regime of retrenchment and austerity that took shape during the Carter presidency and intensified through the Reagan/Bush/Clinton/Bush/Obama years. Positive racial image ideology was the “black” alternative to redistributive and social wage policies. It also amounted to positing individualist solutions to quintessentially collective problems. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, e.g., in a 2018 Baffler essay, “The Trouble with Uplift,” this positive image discourse metastasized over the 1990s and into the current century to a point at which projection of black “heroes” overwhelmed concern with historical accuracy. As boundaries between academic and popular spheres blurred, the logic of the latter increasingly set the agenda for the former.

For instance, scholars closed ranks around Ava DuVernay’s defense of her “Selma” film’s consequential falsification of the history of the Selma campaign in service to the higher purpose of not risking depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as a “white savior.” Similarly, scholars lauded “Django Unchained,” Quentin Tarantino’s cartoonish homage to the spaghetti western, as a more desirable depiction of Emancipation than Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” which attempted – how successfully is another issue, that requires, among other things, taking into account the limits of acceptable artistic license — a faithful portrayal of the machinations attending Congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Others have endorsed the fantasy world created in Ryan Coogler’s superhero film, “Black Panther,” which Coogler called a fable of black empowerment, as an aspirational truth that is thereby truthier than black Americans’ existing realities. This willingness, if not demand, to subordinate the factual world to ostensibly self-satisfying fantasy helps make clear how people who should know better, including scholars, succumb to absurdities like Thirteentherism or Afropessimism that are manifestly false on most cursory inspection.

There’s an element of something like class-skewed moral panic driving this bizarre turn as well. After forty years, the record is indisputable: positive images ideology has failed — abysmally and inevitably — as a special racial antidote to steadily intensifying inequality and material insecurity across the society, among black Americans and others. For the ideology’s purveyors, whose sole critique of the regime of relentless upward redistribution we call neoliberalism is that blacks are overrepresented unfairly among the worst off, and the reciprocal, underrepresented unfairly among the best off, calls forth simultaneously a doubling-down on asserting the ideology’s realer reality and a necessary, though once again unacknowledged, admission of the failure. As the bromides of the positive images Horatio Alger stories become less and less tenable as guides for individual success, sustaining the fantasy as an ideology for popular consumption requires ever greater dependence on magical thinking. From this perspective absurdities like Thirteentherism, 1619-ism, and Afropessimism are attempts, ever more desperate intellectually, notwithstanding the social power supporting them, to preserve a race-reductionist politics by imposing convenient and instrumentally useful fictions onto how we construe actual black Americans’ lives. The ideological arsenal includes also the proliferation of supportive popular mystifications, e.g., prosperity gospel or sacralizing contingent, precarious employment as “entrepreneurialism,” and the sleight-of-hand that there is a “collective black wealth,” which, despite being held by individuals, somehow redounds to the benefit of all black people.

The fetish of entrepreneurialism, in fact, could not be more clearly an update of Booker Washington’s injunction to be the best bootblack one can be, though this time with an additional magical promise that adopting the entrepreneurial self-image might eventually transform itself into prosperity. At the same time, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, several, distinct but related developments in American politics after 2015, not the least of which was the challenge that the forces put in play by Sen. Bernie Sanders’s two campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination sharpened the contradictions at the foundation of the black race-reductionist politics that underlies the predominant strains of allegorical black history, as a result intensifying the aspect of moral panic among its adherents.

To return to The South and its genesis, one of the frustrations that undergirded our conversations was knowledge that for most Americans, probably the vast majority, common sense perception of black American history was a blur in which everything before the victories of the Civil Rights movement between the 1954 Brown decision and the March on Washington or passage of the landmark civil rights laws of the mid-1960s was an undifferentiable, bad old-timey times in which an abstract racism, driven by benighted prejudice, prevailed. This perception was typified in popular references linking “slavery and Jim Crow” as a singular moment. Our lament wasn’t that our stories would be lost, but that, given the dominance of a thin, moralistic ideology of racial liberalism in the academy as well as the general public, when the last living links to the Jim Crow era disappear, the likelihood would be severely lessened that people would be around to play a role like that of Ellison’s “Little Man at the Cheehaw Station,” i.e., to check pathologically inaccurate interpretations from the standpoint of faithfulness to a sense of the range of claims that reasonably might be made about the past and how it can inform understanding of the present. I don’t believe we’d have characterized our concerns in 2000 as a need to counter a consolidating neoliberal antiracism. However, in keeping with my earlier observation noting severed moorings to the strictures imposed by communities of specialized scholarship, this was the period in which Ken Warren and I noticed that applicants to our respective doctoral programs had begun indicating a desire to pursue the Ph. D. as a credential that would facilitate establishing careers in the world of “public intellectuals.”

This reflection may help as well to clarify why, beyond personal idiosyncrasy, I’ve so doggedly resisting defining the book as a “memoir.” Several perceptive reviewers have observed that The South is the opposite or inverse of a memoir.[1] Rather than taking the historical setting of the Jim Crow era as a backdrop for a reflection on my own life or a coming-of-age tale, it proceeds from recollections of personal experience to ground examination of the regime’s features as a coherent social order. Put another way, the book is not an account of how the Jim Crow era produced me, which in any event should be a topic of interest only to my friends and family; it is an attempt to use incidents and features drawn from my life to excavate what the Jim Crow regime was as a social order, where it came from, how it was enforced on, limited by, and reproduced through everyday life, and shaped social relations, expectations and aspirations. The book’s most immediate objective, of course, is to cultivate thinking about the Jim Crow world as a historically specific social formation that was imposed and improvised in response to concrete, immediate imperatives and then fractured, collapsed and was defeated in the face of other imperatives, partly those directly or indirectly generated by the Jim Crow world itself. To that extent, the book is also a brief for the power of historicist approaches to imagining the past. At a higher level of generality, it is as well an assertion of the ultimate truth of Marx’s world-changing but often tendentiously banalized dictum that “It is not the consciousness of men [and women] that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.”

Finally, it’s worthy of note as to how hegemonic the history as allegory approach has become that, when Faith Childs as a favor shopped The South to several trade presses, she not only got no bites; editors, led by the one at Bold Type Books, legatee of Nation Books, who was familiar with my work, reported that they couldn’t make heads or tails of what kind of project it was. It didn’t fit the molds of Up From Slavery narrative or other inspirational autobiography, litany of endless instances of racial oppression and brutality, or the former encased within the latter. Fortunately, the project got to Verso and the deft hands of Asher Dupuy-Spencer, who, in addition to his many virtues and talents as an editor and person, also has immediate family connections to New Orleans (the “Dupuy” led me to suspect as much) and even has intimate knowledge of the Algiers Ferry.

So the chain of fortuitous developments that brought The South into existence, beginning with the early conversations that prompted me to write, through the crucial interventions by Barbara Fields and Faith Childs, to working with Asher at Verso leads me to conclude with rehearsing the two closest things I have as mottos for life – both of which honor the contingency of history: it can be better to be lucky than good, and it’s often more important to be in the right place at the right time and to pay attention, with a bit of sociological imagination of course, than it is to be smart.

[1] On the topic of reviews, I want to acknowledge publicly John-Baptiste Oduor’s immensely generous review essay, “Segregation’s Sequiturs,” in New Left Review. It is meticulously executed with an uncommonly careful, empathetic intelligence. The thoroughness and seriousness of his effort are genuinely humbling; it’s the sort of deeply engaged treatment of which any scholar would dream, a testament to appreciation and respect. It is one the greatest compliments of my career.

0