Last week, we held our annual intellectual history workshop where I teach. The event goes on for two days. For the past five years, a group of us have gathered to read together. We usually start with a “primary source” on day one followed by a guest author’s work in progress on day two. The idea is to combine a primary source with a work on its way to completion or just starting out. (Last year, for example, the special guest was our own Andrew Hartman. We read parts of Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station on day one, and then read some early writing from Andrew’s book-in-progress on Marx in America.)

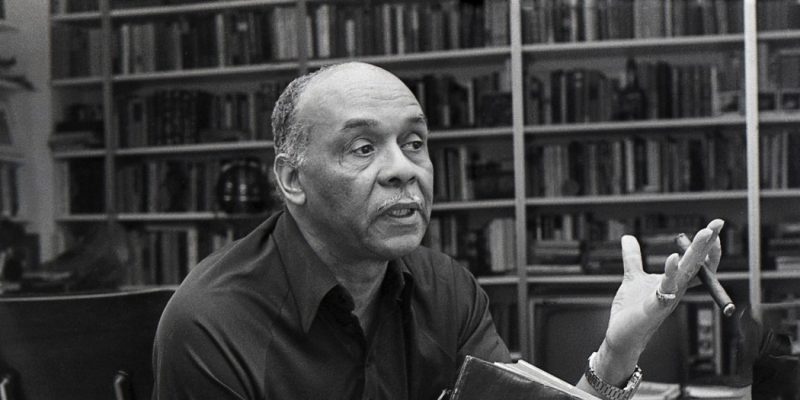

We call it an intellectual history workshop (or at least I do), but the group is made up of people from across different disciplines with heavy representation from the humanities, usually literature people and philosophers. This year we had a couple of social scientists join us (a sociologist and a political scientist). Different from other years, we spent both days on a single primary text. Our special guest this time out was an eminent philosopher from down the road at Vanderbilt University, and one of my mentors in grad school, Lucius T. Outlaw, Jr. We read one of his favorites, Ralph Ellison’s “The Little Man at Chehaw Station.”[1]

Lou led us in a remarkably close reading of that text. The days conjured up the mood in the philosophy courses I took with him while trying to learn how to do intellectual history some years ago. We spent each day reading paragraphs aloud from Ellison’s essay. We went around the room clockwise, and each person read a couple of paragraphs, at which point we’d pause and discuss, jump-started by Professor Outlaw’s Socratic questioning. This generous pedagogy opened up the text beautifully. We listened to each other’s voices, the inflection, the points of emphasis. I’ve read this essay many times now, so hearing others read it aloud was often very different from how I’d come to imagine its sound and rhythm in my head.

Seeing how we spent two days on it, I know for certain there’s no good way to summarize Ellison’s thoughts in the essay in the space of a blog post. I’ll offer a note or two on it taken from our discussions anyway. So what follows begins with our discussions over those two days—but veers off course into my own additions, shapings, and peculiarities.

I think Ellison meant to answer a very old question, one that’s bedeviled political thinkers for a long time, at least since Plato and Aristotle. Can democracies produce truly great art, and can democracies cultivate good taste? There are countless problems of definition here. One could easily give up the ghost before even starting out. What is “truly great art?” and what in the world is “good taste?” The old way of thinking about it, passed down from the ancients and picked up again by Tocqueville for the American case, is that equality can’t recognize the great. In a democratic society, a sentiment of equality reigns. There is no prescribed standard by which one can judge the good and beautiful. Everything arranges around a broad middle or the lowest common denominator. In aristocracies, on the other hand, a select group carries the good and beautiful with it across generations, in its blood and its monuments. This group cultivates taste over time, whether patrons of the arts or producers, in their manners and affect, in the intricacies of social etiquette from forms of address to the arts of the table, and so on.

Ellison unpacked a “riddle” from one of his mentors at Tuskegee, an enormously accomplished, classically-trained pianist named Hazel Harrison (he refers to her as “Miss Harrison” in keeping with a certain polite and now outmoded Southern form of address). After a performance where Ellison “had outraged the faculty members who judged my monthly student’s recital by substituting a certain skill of lips and fingers for the intelligent and artistic structuring of emotion that was demanded in the music assigned to me,” Miss Harrison tells him, “you must always play your best, even if it’s only in the waiting room at Chehaw Station, because in this country there’ll always be a little man hidden behind the stove” (494).

So the riddle, and Ellison’s attempt to answer the very old question, stemmed from how culture moved in a democracy, by whom and for whom, “nothing less than the enigma of aesthetic communication in American democracy” (496). Seemingly at random, mass culture made its way far and wide into unlikely places where unlikely people learned, absorbed, and adapted cultural forms, as presumably “high” art became transformed by the vernacular, and the vernacular was raised to the level of “high” art. It’s uncertain when and where Ellison’s little man might appear, but he showed up, and the artist had to account for him, creating art with the understanding that the man behind the stove could be somewhere in the crowd. Technical skill wasn’t enough. The American audience demanded more. It was central to artistic creation in the United States. American audiences had a special mystery for this reason:

I say “mystery” put perhaps the phenomenon is simply a product of our neglect of serious cultural introspection, our failure to conceive of our fractured, vernacular-weighted culture as an intricate whole. And since there is no reliable sociology of the dispersal of ideas, styles, or tastes in this turbulent American society, it is possible that, personal origins aside, the cultural circumstances here described offer the intellectually adventurous individual what might be termed a broad “social mobility of intellect and taste”—plus an incalculable scale of possibilities for self-creation. While the force that seems to have sensitized those who share the little man of Chehaw Station’s unaccountable knowingness—call it a climate of free-floating sensibility—appears to be a random effect generated by a society in which certain assertions of personality, formerly the prerogative of high social rank, have become the privilege of the anonymous and lowly” (498).

We talked a good deal about Chehaw Station itself, how it was on a switch track into Tuskegee and so would have hosted any number of different people from different backgrounds headed there, mixing in unlikely ways (503, 504). Ellison also mentioned how “many of us, by the way, read our first Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Mann in barbershops, and heard our first opera on phonographs” (499). An intellectual history of spaces and places bubbled up in Ellison’s essay. The beginning of the piece suggested Ellison’s teacher Hazel Harrison, a “prize pupil” of Ferruccio Busoni and “a friend to such masters as Egon Petri, Percy Grainger, and Sergei Prokofiev” (493) was a “little man” of sorts, She cut an unlikely figure her “basement studio” at Tuskegee, if we indulge the old stereotype of that place being dedicated in principle to vocational study alone. Remarkably accomplished people like Hazel Harrison could be found with some frequency in historically black colleges and universities, one of the effects of Jim Crow about which most white folks, it’s safe to conclude, understood very little when Ellison was her student in the 1930s.

Were he alive today, I think Ellison might be pleasantly surprised at the efforts of intellectual historians these days to account for cultural transmission, that phenomenon for which he figured “no reliable sociology” existed. Lots of work in our field concerns just how, where, and with whom ideas have traveled in the United States. We think carefully about institutional sites, the workings of media, books and publishing, image and sound, and so on. Many of our number have been through the paces when it comes to “highbrow,” “lowbrow,” and “middlebrow” and the like. He might be dismayed too, insofar as technical accounts of cultural transmission disenchant the dynamic relationship between artist and audience if explained primarily in terms of mechanisms. I like to think intellectual historians are sensitive to these problems on the whole.

Ellison would have had little patience for formulations like “the culture industry.” He was unperturbed by the “work of art in the age of its mechanical reproduction.” He let pass without much comment the work of art as an object. That many heard their “first operas on phonographs” hardly counted as a problem so much as it posed an opportunity. As we talked about the essay, I thought about Theodor Adorno’s merciless take-down of jazz record collectors, where obsessiveness among those warped personalities stacked up to the worst sort of commodity fetishism. What Adorno saw as symptomatic of the culture industry, Ellison saw as a potential virtue of democracy. Adorno’s pitiful record collector might have shown up somewhere, sometime as Ellison’s sparkling little man behind the stove.

Ellison didn’t say much about the means of production, the mechanisms of it. Rather, his artist produced with an unpredictable but always vigilant audience in mind. He wasn’t all that concerned by the workings of power in this way, about what a capitalist mode of production did to the consumer so much as he tried to account for the diverse constitution of the audience in its dialectical or antiphonal relation with the artist’s constituting of an audience: “By playing artfully upon the audience’s sense of experience and form, the artist seeks to shape its emotions and perceptions to his vision, while it, in turn, simultaneously cooperates and resists, says yes and says no in an it-takes-two-to-tango binary response to his effort” (496). Ellison avoided thinking about “the mass” in the way some critical theorists did. He also understood cultural appropriation as part of the democratic game, whatever the circumstances between borrower and borrowed. Love and theft were inevitable in the workings of a complex democratic culture, as it constantly changed and adapted, pushing ever further into a chaotic, unpredictable future. As we read to one another, I wondered about whether Ellison’s essay offered a theory of democracy while leaving the capitalism part stubbornly unremarked.

It came down to how Ellison poetically described and re-described the “intricate whole.” Diversity answered the age-old question, “complex and pluralistic wholeness” (504) as he put it, punctuated by chance, the unlikely or the unexpected, a natural outcome of the many mixtures and collisions. Ellison was too shrewd to be overly celebratory, so in “Little Man” he acknowledged Americans’ failure to deal with diversity, recognizing how people retreated to the comforts of their own racial and ethnic groups rather than deal seriously with complexity. About Ellison’s version of cultural pluralism much has been said already, and better than I can account for it here.

I was also struck by how, in 1977/78, when the essay appeared, an “age of fracture” was taking shape. It wouldn’t take long before it became outmoded to talk about the whole in the exceptionalist way Ellison did, but the idea does have a stubborn persistence, if not in the fluid, ever-changing “futuristic” way he understood it. Ellison meant to account for the aesthetic problem posed by a democratic polity, but in a decisively black-inflected “American” sense of democracy. To borrow from Booker T. Washington (moving back to Tuskegee in my imaginings), Ellison had us “cast down our buckets” where we were to get an answer to that age old question.

But if the source of the “little man” riddle, Hazel Harrison, is any indication, a transatlantic world or a “Black Atlantic” lay just under the surface. Ellison told us she had lived for a time in Berlin “until the rise of Hitler had driven her back to a U.S.A. that was not yet ready to recognize her talents” (493). One wonders whether Hazel Harrison was ever really at home in the Jim Crow U.S.A., and just what such a declaration of artistic prerogatives and responsibilities meant to her. We talked about something like this problem, about how “Little Man” was less a description of reality than a statement of the possible, or, to use a phrase we puzzled over for a while, “an act of democratic faith” (498).

One of my literature friends mentioned how it might be a good idea to read “The Little Man” alongside Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “American Scholar,” seeing how Ralph Waldo Ellison’s essay appeared in the magazine of the Phi Beta Kappa Society, which bears the name of Emerson’s famous address. It sounded like a good idea. There is a whole lot there to think about some more. Professor Outlaw reminded us that we should pay careful attention to where and how Ellison used the word “America” and where and how he used the term “U.S.A.” That was typically sage advice.

[1] Ralph Ellison, “The Little Man at Chehaw Station, [1977]” in The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison, John F. Callahan, ed. (Modern Library Classics, 2003), 493-523.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Wish I could have been there for this one. Sounded like a great time!