Editor's Note

This is the first of a two-part essay written by Adolph Reed, Jr. The essay, based on a paper he gave at the University of New Mexico for their annual African American History Month celebration, explores recent debates about the uses–and utility–of Black history in both the academic and public spheres. Part two will run next week.

I’m very happy and honored to be the Keynote Speaker to the 38th Annual Kickoff Brunch for the University of New Mexico’s celebration of African American History Month. I want to thank the Department of Africana Studies and the University’s African American Student Services for inviting me. I also want to congratulate members of UE Local 1466 – United Graduate Workers at UNM, who along with UE Local 1498- Graduate Workers United at New Mexico State University signed contracts last month with significant improvements in pay and working conditions. Both contracts were won following months of escalating pressure and are proof that there’s nothing like solidarity. And some of my talk today is going to be about some perspectives that are indeed nothing like solidarity, nothing at all. I want as well to express my special gratitude to Prof. Kirsten Pai Buick, who made it happen. Prof. Buick and I have been an intellectual mutual admiral society for so long that I didn’t recall when or how it began. She remembers and reminded me yesterday.

The topic of memory is actually a good place to start my remarks today. Those who’ve read or listened to interviews about The South know that it began out of an ongoing conversation around the turn of this century with some longtime friends and collaborators who also have personal links to the region in the Jim Crow era. The upshot of those conversations was recognition that our general age cohort were the youngest and soon would be the only people with living recollections of the Jim Crow order as everyday life and that, when our cohort passes from the stage of history, all such connection will be gone. That’s what prompted me to begin writing with no clear end in mind other than to leave a record. Some may also know that I’ve resisted, fiercely and perhaps obsessively, describing the book as a “memoir.”

Marchers in street during Scottsboro protest parade in Harlem, New York, 1931

What I’m sure is less clear is why: why my friends – also professors and scholars who work at least partly on that period – and I were so moved that direct knowledge of the segregation era would die with us, which is after all the experience of everyone who lives long enough to confront that moment? why my immediate impulse was to write something, to leave a record, as though there weren’t already many studies and personal reflections on the period already in existence? and why I’ve so militantly resisted calling the book a memoir? Some answers to those three questions are generic. For example, when it’s one’s own cohort facing the inevitable, the shock of recognition makes it stand out that the cohort (and oneself) before long will persist only ephemerally, in the increasingly remote recollections of others; if you largely contribute to a written scholarly record for a living, then the impulse to capture a sensibility and commit it to text is natural, and, if one’s inclination is to recoil from being center of attention and to abhor whatever could feel like preening self-display, then memoir is anathema as a genre. But there was more. We all fretted, based on trends then current in African Americanist historiography and both academic and popular interpretations of the past, that prevailing ways of thinking about the Jim Crow era, and by extension black American history and American history, were inadequate, in important ways simply wrong, and counterproductive. In the two decades or so since those conversations and since I began to write, the interpretive tendencies we found troubling have become only more dominant as common sense.

What we were reacting to was, on one level, a tension between two fundamentally different approaches to conceptualizing the past and its relation to the present. One sees the link between past and present as generative; from that perspective, the present is connected to the past organically, through a process not unlike evolution. Issues, struggles and the questions or problems that animate them, and other developments that define earlier periods contribute to producing the baseline social and political relations and sensibilities, norms, and frames of reference shaping subsequent ones and so on. So, for example, making sense of contemporary black political and intellectual life is enhanced by situating it in relation to a trajectory that runs from defeat of Reconstruction and Populism, emergence of a new stratum of professional men and women and their discourse and programs of racial uplift at the end of the nineteenth century, the Great Migration from South to North and to cities within the South, which also enabled a mass politics in the 1930s and 1940s and an attendant tension between racial-democratic and social-democratic political norms and aspirations within that politics, eruption of the postwar civil rights movement and the distinct but overlapping articulation of what would be understood as “black interests” in struggles for incorporation in governing coalitions in city politics south and north, and the terms on which the victories of the civil rights movement in the 1960s would be consolidated institutionally.

Examples of literature grounded in this perspective are Preston H. Smith II’s fine study Racial Democracy and the Black Metropolis: Housing Policy in Postwar Chicago and his very recent examination of the dynamics of black political incorporation in cities in the postwar period, focusing particularly on the years prior to Black Power and the Voting Rights Act, “Black Political Incorporation under Neoliberalism: The Routinization of Interracial Urban Regimes,” ; Touré F. Reed, Not Alms but Opportunity: The Urban League & the Politics of Racial Uplift, 1910-1950 and Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism; Kenneth W. Warren, What Was African American Literature?; Michele Mitchell (who, incidentally is from Albuquerque), Righteous Propagation: African Americans and the Politics of Racial Destiny after Reconstruction; Cedric Johnson, Revolutionaries to Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics; Dean E. Robinson, Black Nationalism in American Politics and Thought; Kevin K. Gaines, Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics and Culture in the Twentieth Century; Michael Rudolph West, The Education of Booker T. Washington: American Democracy and the Idea of Race Relations, and Judith Stein, The World of Marcus Garvey: Race and Class in Modern Society and her field-shaping article “’Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others’: The Political Economy of Racism in the United States,” which originally appeared in the journal Science & Society in the winter of 1974/75. (Stein’s work was pivotal in laying out this approach to black political history, including with her “Defining the Race, 1900-1930,” which originally appeared in Werner Sollors’s 1989 collection, The Invention of Ethnicity and was republished in 2019 as part of a three-issue nonsite commemoration of her work and its impact.)

Because it understands the relation between past and present as generative, this approach is also historicist, in that it assumes that the past should be interpreted as much as possible on its own terms, that is, in relation to the specific problems, perspectives, discourses, alliances, cleavages, structures of meaning and feeling that defined the center of gravity of the age and the tensions and contradictions that drove its development. Every historical moment is complex as its own present, and words and ideas can signify quite different, even opposite, meanings in different settings, and the connections between one moment and another are seldom linear or direct. Nor can they be predicted other than after the fact, by means of a kind of rationalist hubris.

E.g., I had fun communicating this point in my teaching by noting that antebellum Democrats’ great victory in prosecuting and winning the Mexican War eventuated in the abolition of slavery. Here’s how it went: the antebellum Democratic coalition was anchored by middling level prosperous southern planters and northern white workers who were joined partly by commitment to Westward Expansion, at one point pumped up as Manifest Destiny, which I’m sure is all-too-familiar to New Mexicans. Tellingly, slippage between pro-slavery and anti-black racist commitments usefully obscured the contradiction at the core of that alliance, i.e., that southern planters favored expansion in order to extend slavery, and white workers wanted it to become yeoman freeholders. (And it’s worth considering that many northern white workers may have been racists because they were Democrats as well as the other way around. Benjamin F. Butler is one illustration of that possibility.) Debates over disposition of the territories acquired via the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and a bit of the Gadsden Purchase, forced confrontation of the fundamentally antagonistic reasons that planters and northern workers wanted territorial expansion. That realization fueled growth of anti-slavery sentiment, encouraged the first two new antislavery political parties – Free Soil and Liberty – led to the meltdown of the Whigs and then emergence of a single, national antislavery Republican party that elected Lincoln president in 1860 on an explicitly antislavery platform, which in turn forced attempted secession of the slave states, and thus created the context for Emancipation.

Recognition of the complexities and unpredictable dynamism of history means that this approach is also contextualist in that it presumes that events, tendencies, and actors in the past are most usefully or faithfully understood first synchronically, in relation to contemporaneous issues, debates, sensibilities, and pragmatic relationships and tensions. How they may be argued to relate to subsequent or present-day phenomena is most credibly grounded on such contextualist interpretation. If you can pardon the plug, the contributions in our collection, Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought, exemplify this approach in relation to the study of black American intellectual and cultural history as does my study W. E. B. Du Bois and American Political Thought: Fabianism and the Color Line. Of course, the generative understanding of the relation of past and present also anchors The South. Perhaps we can discuss whether and how that perspective shows through in the text.

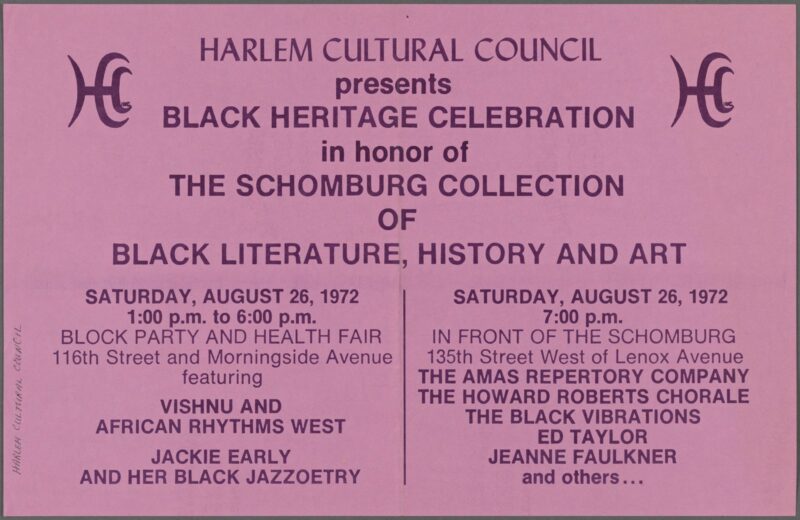

Harlem Cultural Council Presents Black Heritage Celebration in Honor of the Schomburg Collection of Black Literature, History and Art, 1972.

The other approach to examining the past and its relation to the present is allegorical. This approach was prominent when we began our reflections on the Jim Crow world, and it’s almost all there is now. It goes to the past as a source of often cherry-picked “lessons” for the present, a trove of inspiring and uplifting stories, or “anticipations” and cautionary tales. The allegorical approach commonly is driven by identifying and celebrating African Americans’ “contributions” – a notion that also begs interrogation — to America or the world. This reference likely won’t be meaningful to many people younger than 50, but I’ve referred to that variant of the inclination to view history as allegory as the Budweiser Black History Month Calendar approach to black American history – a focus on marking black accomplishments and “firsts.” (Through the ‘70s and well into the ‘80s those calendars, some with themes like black inventors and inventions or Great Kings and Queens of Africa, adorned liquor stores, barber shops and beauty parlors, restaurants, insurance offices, gas stations, convenience and mom and pop stores.) This focus is a vestige of an earlier, and tragic, era when vindication of black people’s capacities was widely seen as an important element of black Americans’ struggle for justice and equality. It also dovetails with and underwrites a sensibility that emerged out of debates over shaping the War on Poverty and the notion that, rather than resulting simply from low wages and unemployment, poverty and economic inequality among black people stem consequentially from demoralization, low self-esteem, and cultural pathologies, as a special sort of “black poverty.” Liberals typically understood the black pathologies as psychically debilitating effects of racism; conservatives were more inclined to see them as reflecting intrinsic black racial/cultural deficiencies, but both views, instructively, wind up at the same place. (As one illustration of the interpretive mischief history as allegory enables, this is something essayist Ta-Nehisi Coates gets exactly backward, as he has claimed that the War on Poverty failed black Americans because it did not take into account the “special” nature of black poverty; that’s precisely what the War on Poverty did, partly in service to justifying partial, segmented anti-poverty policies, and is arguably a reason it was inadequate for blacks and everyone else.) That moment roughly coincided with emergence of a largely psychologistic Black Power discourse, which appropriated what historian Daryl Michael Scott describes as the “damage thesis” about black Americans for radical-seeming ends. It also coincided with the birth of black studies as an academic field, significantly in this context, one that sought its institutional legitimations largely on the basis of what literature scholar Kenneth W. Warren (who is one of the two main communicants who were direct inspirations for what became The South, and is also, for the record, a Burqueño and a former Highland High School Hornet) characterizes as “service to the community,” which he argues in part meant an extramural project of serving black people by “reconnecting them to the vital traditions and habits presumably being drained from everyday life.” Confluence of these tendencies overdetermined appeal of an allegorical approach to history as a foundation for African Americanist scholarship and public commentary.

Although history as allegory is rooted in the desire to enhance black Americans’ place in the historical record and the broader society, it comes at an often-self-defeating price. In abstracting away from historical specificity in service to potted narratives that may seem to satisfy present-centered concerns, it can impede understanding the complex forces that have shaped black American life. Those narratives can also misconstrue and misrepresent realities of the past and its relation to the present in ways that can be counterproductive for pursuit of the laudable overall sociopolitical objectives that motivate that approach. Familiar constructions – e.g., the Negro’s quest for equality or self-determination, black freedom struggle or liberation movement – that stress continuity of black experience across time and context out of concern to emphasize black Americans’ persistence in the face of racial obstacles homogenize black American history in ways that erase historically specific nuances and dynamic tensions that would be important for making sense of the complexities of contemporary black life. [This is a stark contrast to the work of those historicist scholars I cite above.] Some counterproductive consequences of history as allegory do an intellectual disservice mainly to their subject matter, including by not sufficiently insulating interpretive conventions from vulnerability to passing fads.

The curious career of Du Bois’s “double consciousness” formulation in his famous book The Souls of Black Folk is a case in point. For most of the twentieth century the notion was invoked mainly by social scientists, journalists, and civic actors in lieu of evidence to support a claim, which I characterized in my study of Du Bois’s thought as “preposterous,” and will do so again today, that it identified a psychological condition of “two-ness” shared broadly, if not universally, among millions of black Americans. At the same time, the formulation was virtually ignored by literary and intellectual historians, who nearly all considered Du Bois’s challenge to Booker T. Washington to be Souls’s centerpiece. It was not until the late ‘80s and ‘90s that the double consciousness construct suddenly appeared everywhere. Scholars and belletrists, some of whom alleged high-theoretical influences of William James or Ralph Waldo Emerson behind Du Bois’s construct, were quickly joined by journalists and others in finding black double consciousness everywhere. Newsweek even diagnosed O. J. Simpson with the condition in discussing his murder case. I argued that a contextualist examination of Du Bois’s formulation showed that it resonated with a sensibility widely expressed among his cohort of largely northeastern fin-de-siècle elite intellectuals. I argued further that a common root for them all was embrace of the premises of a particular form of the nature/culture dichotomy that was also linked to late Victorian, neo-Lamarckian race theory, which Du Bois accepted in 1897, when he initially published the essay “Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” in which the formulation appears, and presumably in 1903, when Souls was published, but explicitly abandoned not long thereafter.

The point here is not that my interpretation is better, although I do believe it is because it’s richer and most plausible on textualist – i.e., that it fits best with a close reading of Du Bois’s arguments across the trajectory of his career – as well as contextualist grounds. However, that’s a beef between me and other historians of political thought or ideologies. (To be clear, however, I think my interpretation is preferable to the extent that the objective is to produce accounts that strive for historicist credibility but not so much if the objective is to construct a usable past for presentist purposes. However, as I also argue in the Du Bois book, appropriation of the past ahistorically to support presentist claims is not as innocent of historicism as the practice’s adherents contend. When one appropriates a facet of the past to buttress a proposition about the present, one is in fact making at least a tacit claim regarding the historical significance of whatever one is appropriating. In principle, therefore, such claims, even if made for entirely strategic, extramural purposes – e.g., “if Marcus Garvey were alive today, he’d be a Communist” — should be subject to the same standards of evaluation for historical accuracy or plausibility as those advanced on explicitly historicist, scholarly grounds.)

What’s important about this case with regard to my talk today is that by the end of the 1980s the community service orientation in black studies, as embodied, for example, in the emergent category of the “black public intellectual,” had become so prominent that it severed its moorings to critical debates among scholarly specialists about the quality of competing interpretations and became articulated more and more toward public relations and pursuit of career strategies that leverage fame and visibility in the world of public chatter outside the scholarly community for advancement within the academy. As those moorings are severed, restraints on claims one can plausibly make recede in relation to the benefits that visibility in the broad public realm can bestow. This dynamic encourages projection of large, simplistic assertions renderable as easily digestible soundbites often asserting exposé of deeper truths that supposedly theretofore have been ignored, denied, or suppressed by scholars — e.g., claims that the point of the American Revolution and even the Thirteenth Amendment, expressly crafted to abolish slavery, was in fact to preserve the institution. Severing the moorings of scholarly restraint also, in blurring distinctions between scholarship and autodidacticism, diminishes the importance of scholarly expertise as a basis for credibility in advancing such claims. In fact, lack of formal expertise can be its own basis for authority, not unlike the clickbait ads with headlines like “What Doctors Don’t Want You to Know About How to Cure Diabetes.” A parallel move propelling bombastic, dubious assertions concerning black American history is the proclamation of “Things We Weren’t Taught about Slavery’s Role in American History” or the more accusatory question “Why Wasn’t I Taught about Slavery?” (As historian James Oakes points out in “What the 1619 Project Got Wrong,” a powerful recent critique of the 1619 Project in the journal Catalyst, if you didn’t learn about slavery’s central role in American history in college in the last half century, it’s most likely because you didn’t take a U.S. history course or didn’t do the reading or go to class. I would add, unless you went Bob Jones or Liberty university, Hillsdale or another right-wing college.)

In this environment questionable, or flatly erroneous and ahistorical interpretations have had much broader impact. I’ve already mentioned Coates’s exactly wrong characterization of the War on Poverty’s premises regarding black poverty, which led him to misdiagnose sources of, and therefore propose inadequate remedies for, black economic inequality in the present. Thirteentherism, or the argument that the Thirteenth Amendment did not abolish slavery but included a poison pill in its exception for “punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” that enabled the institution’s rebirth as mass incarceration, illustrates the mischief that what Daryl Michael Scott in a 2022 article, “The Scandal of Thirteentherism,” in Liberties magazine calls “bad history” can encourage. This claim, which rose to widely held common sense in the wake of Ava DuVernay’s 2016 documentary, 13th, is based entirely on a tendentious and historically uninformed, naively textualist reading of the Amendment, combined with just-so stories and at least — but not always only — implicit conspiracy theory that, as Scott notes, brings to mind the devil theories of the Nation of Islam. Scott and historian Sean Wilentz in a December, 2022 New York Review of Books article, “The Emancipators’ Vision,” have catalogued the many inadequacies and historical misreadings on which this claim depends. One failing that Wilentz indicates, to which autodidacts may be particularly vulnerable, is “imputing causes from results,” though in fairness to autodidacts the culprit to whom Wilentz refers is a triply Harvard-degreed full professor at Tufts. The Thirteentherist case, in line with interpretive tendencies like Afrofuturism and Afropessimism that willfully break with strictures of temporality and chronology to facilitate telling a desirable story, often seems to have later events causing earlier ones and persistently presses historically erroneous claims on the ground of exposing a truthier truth. (As Scott argues, this rejection of the integrity of historical truth is at odds with more than a century of black American intellectual life, which hinged on conviction that historical accuracy was a handmaiden of the struggle for racial justice and equality.)

0