The Book

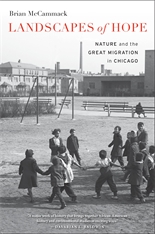

Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago

The Author(s)

Brian McCammack

Brian McCammack’s Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago brings together two fields of study critical to twentieth century American intellectual history: environmental history and the history of the Black Great Migration from the South to the American North and West. McCammack wisely sets his book in Chicago, the heart of the Great Migration and a city that, like many other urban centers in America during industrialization, wrestled with how to provide its residents with fresh air, walkable land, and a sense that nature was never far away. While many Americans did seek respite from the grime and hardship of urban living, Black Americans had to deal with the structural racism that made the pursuit of leisure in the outdoors so difficult. This all combines in McCammack’s narrative to form a fascinating narrative of Black life in Chicago.

McCammack, an Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at Lake Forest College, makes clear in his book that Black Americans living in Chicago always sought ways to hold on to the outdoors as a way not only to enhance their quality of life in the city, but to stay connected with their earlier living environment in the mostly rural South. “But although nature no longer factored into most migrants’ working lives as directly as it once did,” writes McCammack, “it remained integral to their culture, both recalling a way of life left behind and offering a complement to modern urban conditions” (5). In this way, Black Americans attempting to connect with nature while living in Chicago were also trying to connect with earlier ways of living—whether those they experienced or those experienced by parents who moved to Chicago—striving to hold on to what was important to them in the face of a fast-paced, “modern” life in Chicago.

This experience of Black urban life in Chicago was not without class difference, however. This is a critical part of McCammack’s narrative: the need for well-to-do Black Americans to show how well off they were by seeking outdoor spaces not easily accessible for the Black working class. As McCammack points out, “nature often meant something different for a working-class domestic worker or stockyards laborer than it did for a member of the black cultural elite like Jesse Binga” (8). The intra-class conflict over use of the outdoors is as fascinating, and important, as the interracial clashes over access to many of the same spaces.

When one considers how Chicago has become an integral part of Black American history in the twentieth century, Landscapes of Hope takes on even greater meaning for scholars and non-academics alike. Recent works such as Richard Courage and Christopher Robert Reed’s Roots of the Black Chicago Renaissance, or E. James West’s Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr., among other works, make a case for the Second City to have its own place in the sun within Black American intellectual history. What makes McCammack’s work integral within this subfield is how he ties in the history of Chicago’s environment to these broad questions of race, class, and identity in Chicago. When McCammack argues that Black Americans in Chicago “grafted not only race but also a cultural geography of North and South onto spatial and ideological boundaries” within Chicago’s various parks, it makes the case for how expansive intellectual history can and should be—and how that offers opportunities to think about how those outside the traditional centers of intellectual thought help to give shape to the ideas of any era (21).

The book is divided into two sections for a combined five chapters. Part I, “The Migration Years, 1915-1929,” covers how early Black migrants to Chicago rapidly changed the expectations of who enjoyed the outdoors in and around Chicago. At the same time, events such as the 1919 Red Summer Riot, attacks on Black Americans moving into previously all-white areas of the city, and the growing power of the Black-run newspaper Chicago Defender all help to shape how Black Americans interacted with the park and outdoor networks of Chicago.

Part II, “The Depression Years, 1930-1940,” showcases how Black Chicago came into its own when creating its own outdoor spaces, while having to confront the ravages of the Great Depression era. At the same time, the New Deal’s programs—most notably the Civilian Conversation Corps—provided younger Black Americans, many of whom knew only life in Chicago, new opportunities to experience nature and the Great Outdoors. As an example of this, Chapter 3, “Playgrounds and Protest Grounds,” adroitly combines the middle-class concerns about racial uplift with the use of green spaces by Chicago’s Communists to protest against the harsh conditions of Depression-era Chicago, and attempts to forge a multiracial coalition. As noted in Landscapes of Hope, “one activist recalled that Washington Park was ‘the center of protest by Blacks against all forms of oppression’ during the Great Depression” (110).

Outdoor spaces may appear to be politically and racially neutral. Yet, as McCammack argues in Landscapes of Hope, American environmental and intellectual history are best served when they work together to create a nuanced, critical interpretation of the past and how different groups of Americans utilized and viewed the outdoors. Such is the case here with Black Americans in Chicago.

About the Reviewer

Robert Greene II is Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University, an historically Black university in South Carolina, and Senior Editor for Black Perspectives, the blog of the African American Intellectual History Society. He is currently Chair of Publications for S-USIH. He previously served as Book Reviews Editor for S-USIH and has blogged for the site since 2013. Greene’s research interests include African American history, American intellectual history since 1945, and Southern history since 1945. He is the co-editor, with Tyler D. Parry, of Invisible No More: The African American Experience at the University of South Carolina (University of South Carolina Press, 2021). In addition to his scholarly publications, Greene’s public history commentaries and reviews have appeared in The Nation, Jacobin, Dissent, Scalawag, and Current Affairs.

0