The Book

Battle Green Vietnam: The 1971 March on Concord, Lexington, and Boston

The Author(s)

Elise Lemire

It was none other than Ho Chi Minh who first compared Vietnam to America during our country’s War of Independence. In his own declaration of independence made on September 2, 1945, Ho famously paraphrased the opening of the American declaration document and parsed its sentiments to the Vietnamese crowds gathered to hear the anti-French colonial revolutionary in Hanoi’s Ba Dinh Square. In invoking the political rhetoric of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Ben Franklin, and Roger Sherman, Ho sought to establish historical parallels between his efforts at escaping colonial subjugation and those of the world-famous revolutionaries who wrested their independence from the British empire and launched an innovative political system that stressed peoples’ rights over the powers of monarchs and aristocrats. A quarter-century later, some American war veterans who had recently returned from fighting in South Vietnam similarly invoked the actions and ideals of the American Revolution as part of a desperate cause. And like Ho, they sought radical political change by imitating historical examples drawn from America’s War of Independence.

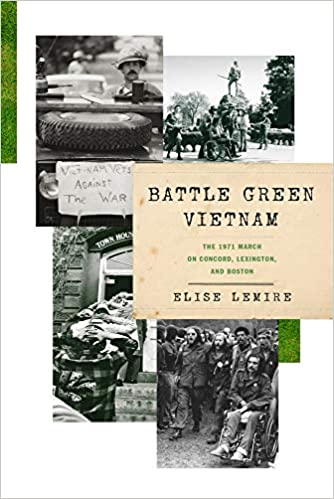

In Battle Green Vietnam: The 1971 March on Concord, Lexington, and Boston, Elise Lemire examines how a small group of disillusioned veterans exploited the sacred aura of America’s birthplace to press their government for disengagement from Vietnam. Lemire traces their geographical and rhetorical progress as they traversed the battle road from Concord to Lexington before reaching the Boston Common on Memorial Day Weekend in 1971. Lemire, a literary scholar who has published other books and articles on this area and era, argues that a nucleus of historically minded veterans, many of whom had grown up in the history-heavy towns around Boston, utilized Americans’ reverence for Paul Revere, the colonial minutemen, and other figures of the American revolution to draw attention to, and to frame, their anti-war cause. Having grown up amid the historical markers of the American Revolution – the many plaques, statues, battlefield markers, and cemeteries of eastern Massachusetts – these veterans were keenly aware of the almost religious significance that these places held in the nation’s collective imagination. Their intimacy with the area allowed these soldiers-turned-activists to achieve maximum effect for their political theater. They displayed 20th-century U.S. military tactics in the now-quaint town centers and well-manicured village greens of what had once been colonial New England. Along the way, they garnered more attention and sympathy than earlier university-based anti-war protests had achieved.

By early 1971, after several years of campaigning for withdrawal, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) activists had grown frustrated with the meager results of their political agitation. Earlier marches on Washington, DC – a site of myriad political messages – had failed to spark the popular support they deemed necessary to end the war. With their focus on the national capital largely fruitless, they turned their attention to the cradle of American independence as a potentially more affecting arena for their political performance. The American veterans opposed the war for several reasons. They believed that the U.S. military was acting immorally. Our forces’ indiscriminate killings of Vietnamese people, including many non-combatants, had left many veterans disgusted and traumatized. These veterans had seen how even an ethical and well-trained soldier could commit atrocities when combatants and innocents looked alike. Modern America, they argued, has ceased to be the beacon of democratic ideals fostered by the founding fathers. Instead, it had become a violent imperial power with little desire to reflect on the righteousness of its foreign wars. But they acted mainly out of concern for their fellow soldiers still fighting in Vietnam. With President Richard M. Nixon’s plan for withdrawal underway – a process of turning the ground fighting over to South Vietnam’s military – the remaining American troops felt unsupported, vulnerable, or even abandoned.

In examining the many photographs that enliven Battle Green Vietnam, I was struck by how familiar the faces of the VVAW’s leadership were to me. Images of the shaggy young men in motley military uniforms carrying anti-war placards have illustrated countless textbooks and general histories of the war. But except for former U.S. Senator and Secretary of State John Kerry, I knew almost none of the other veterans’ names or personal histories. Lemire remedies these lacunae by exploring the biographical details of several of these VVAW leaders to convey her scholarly arguments. Lemire uses one veteran’s story to anchor each of her six chapters while weaving in the stories of others who joined or supported their movement. Her use of the veterans’ first names emphasizes the intimacy she brings to each figure and their motivations for joining the movement. Lemire presents her human subjects in all their complexities by considering their childhoods, evolving world views, service in Vietnam, and the emotional and psychological trials they endured as returned soldiers. She shows them as Americans from across the political and socio-economic spectrum who found common cause in a desperate attempt to rescue America from the deadly trap it had engineered for itself in Southeast Asia.

Among the strengths of this study is Lemire’s deftness at conveying the sometimes-raw feelings generated by the VVAW’s harsh-but-efficacious guerrilla theater methods. Adorned with toy M-16 rifles and real combat helmet liners, the veterans staged mock “search and destroy” missions in these most picturesque of New England suburban towns. They tried to recreate for the American public (and press) the sometimes-brutal interrogation methods used by U.S. troops in Southeast Asia. Their goal was to expose violence inflicted on Vietnamese civilians and its psychological cost on the U.S. troops perpetrating it. The VVAW leadership believed that if Americas experienced or observed these encounters in towns like their own, the war would become less remote and abstract, and the “silent majority” would be less likely to support their government’s intervention. Lemire’s descriptions of these tactics are arresting. Her excellent research turns up recollections of several women who agreed to aid the veterans as they demonstrated their hardhanded methods before crowds of unsuspecting onlookers. The fear and near-panic these collaborators felt while being subjected to the harsh tactics offer an unsettling insight into the genuine terror experienced by the Vietnamese villagers who endured the actual treatment.

While tracing political and personal developments over this long weekend, Lemire highlights collective cultural truths about American society. War-as-play has long been an acceptable – and even encouraged – pastime for American boys. Lemire shows how the mock assaults and plastic guns sparked discomforting revelations about the violent-themed games central to the American boyhoods of nearly all the veterans in her study.

Further bolstering her sharp analysis is Lemire’s description of the “shape-shifting” process that the anti-war veterans underwent along the way. They go from imitating Paul Revere – patriotic clarions warning the American people of the tragedy unfolding in South Vietnam – to mimicking the British redcoats by demonstrating how they harassed and abused farming folk and town officials in Southeast Asia. This transformative process seems as psychologically grueling as any military engagement.

Lemire’s Battle Green Vietnam comes at a good time. While the public image of the Vietnam War veteran has improved considerably since the 1970s, the anti-war veterans in Lemire’s study have not always been remembered well. The “swiftboating” of Kerry during his presidential run in 2004 – an effort at disputing his military record while questioning his national loyalty – exposed the lingering strains of hostility that some still harbor for veterans who pursued patriotic dissent, even when they directed it at protecting the lives of American soldiers. More recent political fights over the history of our colonial past, notably the vehemence leveled at the contributions in Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, are further reminders of the sacred place that our creation story holds in the national imagination and the righteous anger aimed at those seen to be tampering with it. Battle Green Vietnam is a lucid and well-researched study that should be read by scholars of the Vietnam War and America’s history in the post-WWII era.

About the Reviewer

Richard A. Ruth is a professor Southeast Asian history at the U.S. Naval Academy. He specializes in Southeast Asia’s cultural history during the 1960s and ‘70s. He is the author of In Buddha’s Company: Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War (2010), A Brief History of Thailand (Tuttle 2021), and numerous articles and chapters on the Second Indochina War and Thailand’s history.s a professor Southeast Asian history at the U.S. Naval Academy. He specializes in Southeast Asia’s cultural history during the 1960s anRichard A. Ruth is a professor Southeast Asian history at the U.S. Naval Academy. He specializes in Southeast Asia’s cultural history during the 1960s and ‘70s. He is the author of In Buddha’s Company: Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War (2010), A Brief History of Thailand (Tuttle 2021), and numerous articles and chapters on the Second Indochina War and Thailand’s history.d ‘70s. He is the author of In Buddha’s Company: Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War (2010), A Brief History of Thailand (Tuttle 2021), and numerous articles and chapters on the Second Indochina War and Thailand’s history.

0