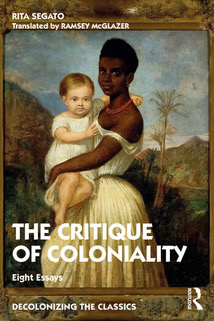

The Book

Critique of Coloniality: Eight Essays

The Author(s)

Rita Segato, translated by Ramsey McGlazer

Decolonial studies is one of the most exciting and important developments in recent Latin American scholarship. Scholars working to decolonize the production of knowledge—among them, Aníbal Quijano, Immanuel Wallerstein, Enrique Dussel, Antonio Negri, Walter Mignolo, and Rita Segato—have uncompromisingly analyzed how Latin America’s colonial history continues to shape every aspect of contemporary life in the continent. Decolonial scholars insist that concepts of race were central to the European conquest and exploitation of the western hemisphere, and remains a central theme of modernity. Segato, an anthropologist from Argentina who taught most of her career in Brazil, brought feminist analysis to the decolonial project. Her articles and books have shaped international discussion of gender and violence, racial formation, and indigenous autonomy. Recent recognition for her contributions to international scholarship include the Latin America and Caribbean Prize from the Latin American Council of Social Sciences (2018), the Daniel Cosio Villegas Prize from the Colegio de México (2020), and the Frantz Fanon Prize from the Association of Caribbean Philosophers (2021). Segato currently holds the chair in “Pensamiento Inquietante” (“Disturbing Thought”) at the University of San Martín in Argentina and the Aníbal Quijano chair at the Queen Sofia Museum in Madrid.The publication of The Critique of Coloniality: Eight Essays introduces Segato’s ideas to English-language readers. Three essays in the book explore the roots of decolonial studies with indepth investigations of Aníbal Quijano and José Carlos Mariátegui. Other essays examine Segato’s feminist commitments and the work she calls, “anthropology on demand,” where Segato has used her professional skills to assist indigenous communities asserting their right to self-determination. The eight essays present examples of how colonial structures continue to shape identity and everyday life in Latin America. Segato argues that race remains the essential and most effective instrument for European domination.

Race, according to Segato, is more than a classificatory and hierarchizing operation of science. Race created living collective subjects, communities formed through extreme historical alienation. She argues that in order to foster a historical and political imagination sensitive to the pain of others, new ways of speaking about social relations are needed. Familiar forms of expression have been central to the construction and perpetuation of machismo, the minimization of indigenous rights, and how the public responds to anti-racist struggle. She insists on the need to integrate principles that often discussed apart. She discusses her work with the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies to develop human rights legislation that recognizes Brazil’s multiple historicities. Segato argued that in reforming how the judicial process operated in indigenous communities, the government also needed to consider indigenous perspectives about the past and their relationship to the Brazilian nation. The principle motivating human rights legislation that the nation’s citizens had to be protected from violence would most effectively achieve those goals when combined with the principle of protecting the autonomy of indigenous life. In a country where the modern state and the church have historically been the primary source of violence against indigenous people, especially against indigenous women, the nation must acknowledge the right of each people to find solutions to the problem of violence in their own history and customs. Human rights must include the right of indigenous communities to exist and defend themselves. This was a moment when many Brazilians believed that efforts to expand democracy would succeed to the degree that they were linked to addressing the status of indigenous populations within the republic.

Latin America is one of the most unequal regions in the world. The historical narratives academic knowledge has produced have operated to glorify the state while inhibiting formation of a new social imaginary able to overcome economic and intellectual dependence on the global north. Decolonial studies continues previous efforts in Latin America—liberation theology, dependency theory, Paulo Freire’s “pedagogy of the oppress”—to counter a moral subordination that perpetuates the “civilizing mission” of the white man. Failure to understand the role of race in shaping Latin American societies has compromised projects for social and economic change, both liberal and socialist. Typically, the left insisted that class relation explained all inequality. Liberals imagined that the racially mixed population in most Latin American countries meant that the continent had become a “racial democracy.” Decolonial scholars argue that race was a primary instrument of conquest and colonialism, structuring the relations between indigenous peoples, blacks, and white in forms that continue to the present. Further, the historical record reveals no instance of capitalism that did not rest on racialized inequalities. Race has been and remains the fundamental relational concept of modern life, a concept that extended colonial rule into the present. Segato argues that both liberals and socialists distrust non-white ways of life, which they see as obstacles to national progress. Resistant and insensitive to indigenous demands, both liberals and socialists have stood in the way of their nations exiting coloniality and building truly democratic institutions.

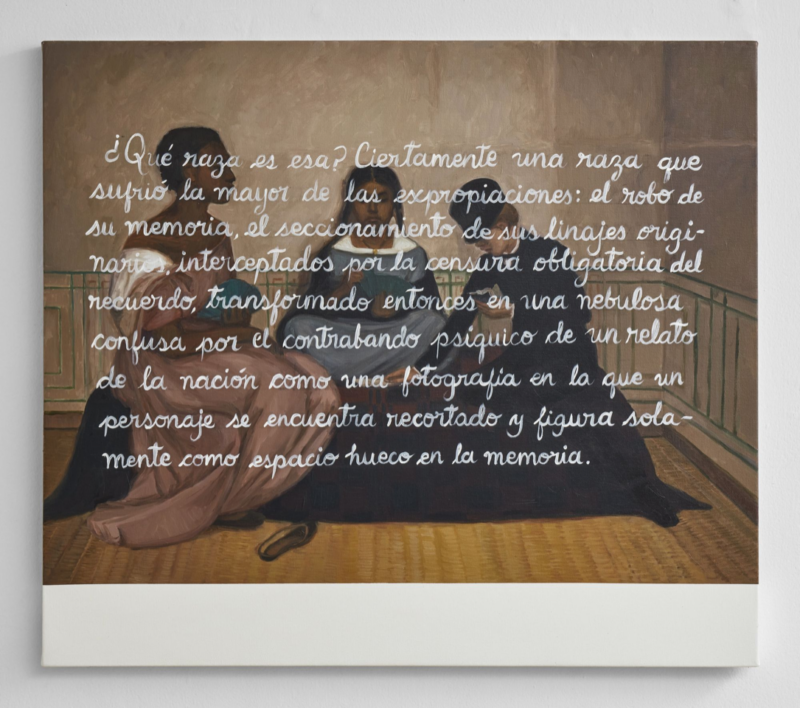

Throughout the continent, there are many communities whose continued resistance to domination has kept alive modes of social relations that are foreign to what colonial discourse and state political power prize. The decolonial turn finds hope in the paths that resisted colonization and the modern state. The Andean category of “Buen Vivir”/“Sumak Kuasay” (“Good Living”) presumes social relations constructed around the principles that humans are part of nature and connected to all other living beings. It is an idea that holds that cooperative human relations with the natural environment provides a more materially secure and spiritually content life than concepts such as productivity, competition, or accumulation of wealth. An understanding of community as going beyond social relations to encompass everything surrounding humans defends spiritual beliefs and practices that are symbolically dense and historically deep. The way of life promoted is capable of producing wealth but not with the goal of turning everything into capital. As the product of another historical experience that has been forced to experience the sorrow accompanying five hundred years of material accumulation, the “Good Living” movement in the Andean countries is most committed to the links between living beings. It is an expression of life capable of moving society into possible futures that still colonized societies cannot access. We can see a recent example of this thought in the painting My Three Races by the Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra. The text in the painting is a quotation extracted from the writing of Rita Segato.

The future that modernity promised has been marked by a series of linked binary oppositions: pre-capitalist societies/capitalism; non-European/European; primitive/civilized; tradition/modernity; magical/scientific. These binaries objectified both nature and “the others,” who become, Segato notes, objects of a pornographic gaze. Ideals of neutrality, pragmatism, scientific development justify what Segato what Segato calls a “pedagogy of cruelty.” The result is known to everybody alive at this moment, but those who suffer directly from environmental devastation, the pillage of their homelands, and the alienation of their histories do not see “progress” arriving at any end point that could conceivably justify the pain.

The Latin American university today embraces the ideal that historical consciousness should be rooted in the land and national conditions, but then most scholarship still proceeds out of Eurocentric epistemologies that reproduce epistemic racism. For this reason, Segato has made José Carlos Mariátegui, a Peruvian social theorist from the 1920s, a central reference in her book. Mariátegui rescued Marxism from its Eurocentric prison by using it to rethink indigenous knowledge derived from a long relationship with the Andean landscape, while simultaneously using the indigenous reality of Peru to read Marxism in new and unexpected ways. For Segato, Mariátegui provides an indispensable starting point for thinking a new type of political thought, a new type of modernity, freed from colonial rhetoric. Mariátegui’s ideas and example appears in every chapter of this, though not every invocation is cited in the endnotes.

In her examination of racism in Latin American universities, using the case of racial quotas that the Workers Party introduced after 2002 when Lula da Silva was elected president, Segato warns against the false democracy of academic institutions. The power relations at stake are fundamentally meritocratic. The process adopted served to open doors only for a few. Rather than rethink the place of higher education in the nation, an ostensibly anti-racist program valorized unfair competition and justified the narcissism of those who came out ahead. Those inside the academy remained convinced that history unfolds in ways that produce progress. Not quite. Multiple historical paths are to be found inside the university, many more even outside. Making the university more humane and accessible, more responsible for collective well-being, remains a goal. Without examining the racial discourse at the heart of progressive understandings of the past, we will not recognize the violence that continues to be visited on indigenous communities, in particular on indigenous women. We will not understand the reality of mass incarceration in our societies. In Latin America, there are many problems that are invoked but for which there is very little data available that would help to get beyond a politics of sentimentality. According to Rita Segato, it is necessary to recover old knoweldge in the threads of stories people share. There are to be found the forgotten paths forged in a world that talks about justice and prosperity, but somehow never for the majority. I highly recommend Segato’s book as an introduction to an engaged intellectual, committed to a plural understanding of history. She expresses in this power book her extensive research into the history of modernity and its connections to feminism, racism, colonialism, indigenous power, and the role scholars have to play in reopening what the future could be.

Mis tres razas (2021) – Work by Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra featuring the words of Rita Segato: “What race is this? Certainly a race that suffered the greatest of expropriations: the theft of its memory, the severing of everything that connected people, caught up in obligatory censorship of memory, transformed into nebulous confusion through the psychic imposition of false narratives of the nation. It’s like encountering a photograph where we see that somebody has been cut out and appears only as a hollow space in memory.”

About the Reviewer

Priscila Dorella is Associate Professor of History at the Federal University of Viçosa (Brazil). Dorella is the author of Octavio Paz: Estratégias de Reconhecimento, Polémicas Politicas e Debates Midiáticos no México (São Paulo: Alameda, 2015). She is currently working on a book on Susan Sontag as a transnational intellectual.

(translation by Richard Cándida Smith)

0