The Book

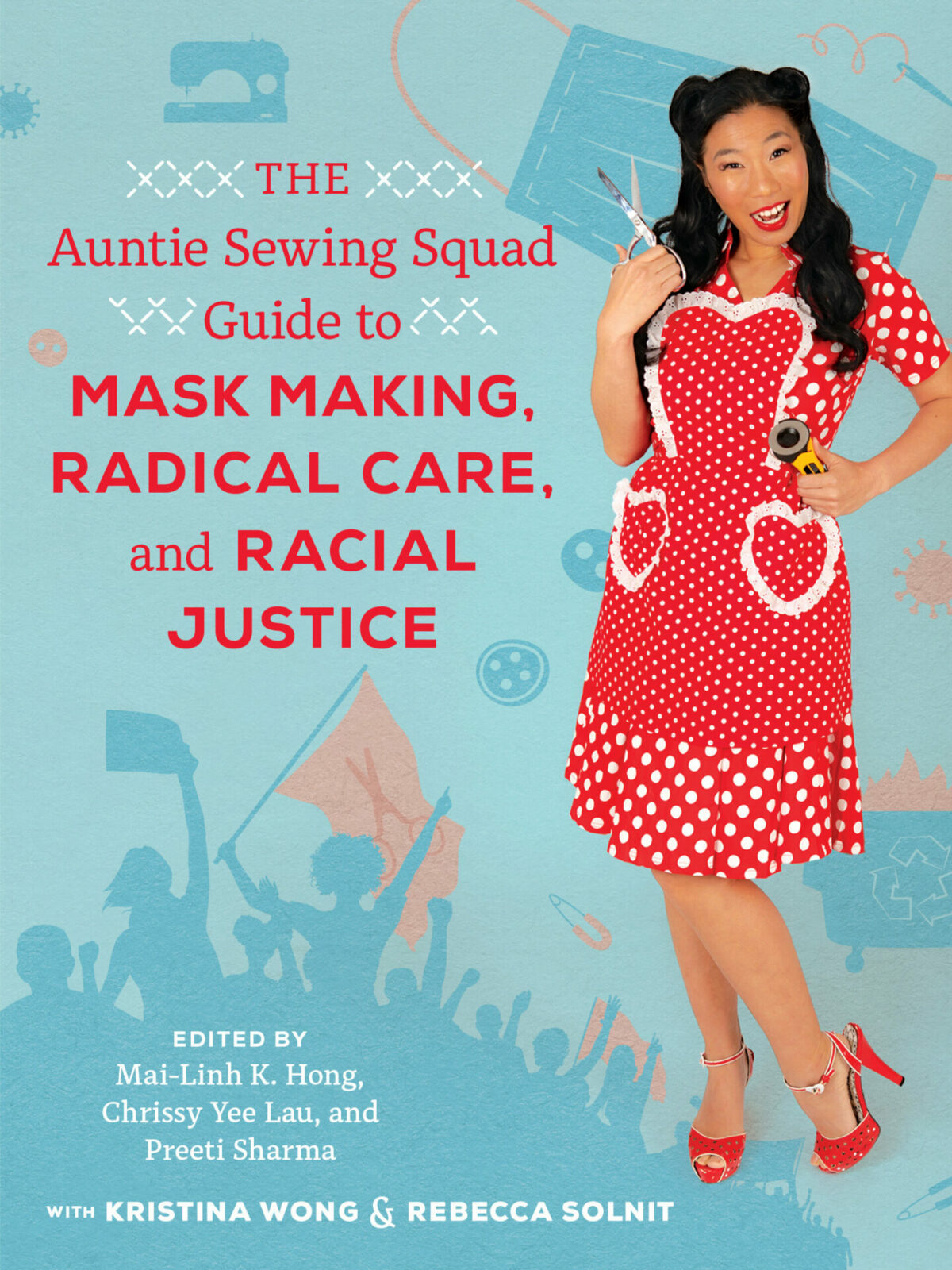

The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice

The Author(s)

Mai-Linh K. Hong, Chrissy Yee Lau, and Preeti Sharma with Kristina Wong & Rebecca Solnit

Editor's Note

The Auntie Sewing Squad formed in March 2020 with three “sewists” (the preferred term instead of sewers) and quickly ballooned into two thousand in just few days. By April 2020, there were eight thousand members. The Squad is chiefly made up of Asian American and other people of color who identify as both cisgender and nonbinary (Aunties, Uncles, and Unties). Many participants are academics and educated professionals from immigrant families who have had the privilege of time and resources during the pandemic to sew masks to protect underprivileged communities such as those seeking asylum, Indigenous communities, recent parole recipients, transgender immigrants, urban farming coops, trafficking victims, and low-income BIPOC groups. The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice is an energizing and aesthetically brilliant history of radical responses to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Not only does it figuratively suture interracial and intersectional communities, it also demonstrates the conceptual interstices between performativity, ironic humor, carework, and reappropriation of political failure. The book’s reclamation of moments and terms of political failure and oppression is its key move. In The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide, the performative recasting of the lowly and retrograde through ironic exaggeration and absurdist comedy becomes a path to potential radical action.

Edited by critics and esteemed “Aunties,” Mai-Linh K. Hong, Chrissy Yee Lau, and Preeti Sharma, together with the performance artist Kristina Wong and feminist writer and activist Rebecca Solnit, the book begins with a revelatory preface by Wong, the comically self-declared “Sweatshop Overlord” of the Auntie Sewing Squad. In the preface, she explains her appropriation of the term “sweatshop,” reclaiming it for financially privileged volunteers who seek to address the federal government’s failure, under Donald Trump’s administration, to come to the aid of endangered populations in the U.S. Before the pandemic, Wong, was slated for a national tour of Kristina Wong for Public Office, a show about her election to a seat on her neighborhood council in Koreatown, Los Angeles. In the Preface to the book, she comically redirects potentially offensive terms of exploitation to more progressive ends. She performs her role as “Sweatshop Overlord” by wryly advertising the services of the Auntie Sewing Squad, shortening the group’s name to the absurd acronym ASS. It’s a way both to point to and reject the historical hypersexualization of Asian American women by shifting the offensive term to connote honorary family members and progressive aunties. She facetiously threatens to cut off the fingers of unproductive aunties in the squad and encourages voluntary child labor. The exaggerations point to the absurdity of stereotypes while also emphasizing the problems of economic and cultural injustice that accompany them. Wong sarcastically writes, “If you’ve ever wanted to exploit unpaid manual labor, coerce children to help you, and be lauded as a hero, you have come to the right place” (xv).

The exaggerated, performative quality of the writing allows the Auntie Sewing Squad not merely to offer critique, but also to imagine alternative solutions to the immiserations of the COVID-19 era. Theorists such as Judith Butler made performativity a popular theoretical term in the 1990s, but after performativity dismantles heteropatriarchy by deconstructing gender, heterosexuality, and race, the question remains: what can performativity positively produce? This book offers an answer: intersectional mutual aid. Citing legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality in the 1980s, editors Hong, Lau, Sharma, along with writer Valerie Soe, argue that the Auntie Sewing Squad demonstrates intersectionality’s very definition of the complexity of the interaction of race and gender and the insufficiency of the single frameworks of race and gender to discuss the identities of women of color. What intersectionality can produce is not only the understanding that no one structural inequity dominates, but also that mutual aid can emerge precisely out of intersectionality. The Auntie Sewing Squad writers argue that their work becomes “specifically feminist and intersectional.” Their insistence on “solidarity, not charity”—the rallying cry of mutual aid—arises directly from histories of migration, labor exploitation, and racialized gender oppression. Women of color, poor women, immigrant women, nonbinary and transgender people, and others who inhabit multiply marginalized identities move to the center in these interlocking histories of struggle. So it is in this book that the Auntie, a female cultural figure often associated with conservative traditions of family and custom in minority communities, now emerges in reimagined form as an icon of progressive activism embodying the principles of radical care and mutual aid during the COVID-19 pandemic (12).

At the center of the Squad’s activities is the act of sewing. Many of the Aunties wrote that in the face of the federal government’s inaction and downplaying of the severity of the pandemic and its continued racist policies and discourse against Latinx asylum seekers, African Americans, Native Americans and Asian Americans, they sewed. So too, contributor Mai-Linh Hong writes that particularly during the harrowing period of the Kavanaugh hearings that punctuated the #MeToo movement, she turned to sewing for respite; she writes:

For many years now, I have benefited from sewing as a mindfulness practice. While the Kavanaugh confirmation careened to its inevitable, sickening conclusion—putting a likely sexual assaulter and spoiled man-child on the highest bench in the land, where he would have a role in deciding women’s right to control their bodies—I sewed. Often I sewed instead of writing, eating, or exercising. (142)

Sewing, however, led to other practices and ideas about mutual support. In contrast to the patronizing notion of charity, mutual aid offers a critique of capitalist productivity: it specifically responds to systemic damage with the intention of inciting political change through shared actions by equals who draw upon their differences as well as their similarities (41-42). In this spirit, the Squad includes a Community Care Coordinator who makes sure that all the Aunties, Uncles, and Unties are fed while they labor at sewing. Squad members deliver to each other gifts of baked goods and ethnic dishes in acts of reciprocity and support. Sewing becomes about far more than just sewing.

In the book, the Auntie Sewing Squad also reclaims the stereotype of Asians as a model minority. Lau writes the Squad’s tenet of “sewing with intent” redirects the myth of the model minority from the stereotype of the “law-abiding, self-sufficient, and not Black” Asian American, which has been used by whites to derail African American civil rights activism. They redirect it to support the Black Lives Matter movement instead. The book documents the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, which sparked the 2020 BLM protests. In addition to sewing masks to protect BLM protesters and participating in protests themselves, the Aunties also sewed masks for the Navajo Nation, which had more cases of COVID-19 per capita than any other state by May 2020. A few of the Aunties were inspired by the 2016 #NoDAPL protesters of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) to also sew as an act of aiding the Indigenous communities affected by the effort to construct the pipeline. The Auntie Sewing Squad did not merely sew for others; most intriguingly, its work attracted new members such as Latinx sewists. Against the harm enacted by the model minority stereotype, which divides Asian Americans from other ethnic minorities, the Auntie Squad formed and solidified interracial alliances through the shared labor of sewing and the comical but dedicated culture they developed around it.

The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice does not just offer reflections on interracial care and radical justice during the COVID-19 pandemic, it also strives to enact care through its very design. Figuratively sewing together illustrations, maps, comics, recipes, and mask patterns along with its historiographic essays about the pandemic and documentation of the work of the Squad, the book is a graphical masterpiece. The book begins with a montage of pictures of the different Auntie roles (xvi-xvii), followed by a colorful, checkered “ASS bingo” board (25), photographs of Aunties at work or in protest (29, 69, 81, 87, 92, 99, 191, 205), mosaics of fabric and masks (33, 107, 119, 152, 234), quilts (184-185), and a graphic portrayal of the taxonomy of Auntie Care (56-57). These pieces reflect what the book does to stitch together the intersectionality, performativity, reappropriation, carework, and ironic humor of the Auntie Sewing Squad.

Comedy brings levity to a grim global situation in this book while also serving as serious social critique that opens up new possibilities for radical action in solidarity across different oppressed groups of people. So too does the conscious choice of what might best be called contingency by Squad members: in their “Core Values,” the Aunties write, “We seek to be obsolete, not profitable” (22). The Auntie Sewing Squad’s comical performativity, their appropriation of seemingly offensive terms, their redirection of capitalist productivity toward mutual aid, their rejection of the model minority stereotype—these all offer fresh modes of seeking racial justice through creative means that welcome others to join in with them. Here is a book about voluntary, radical collective carework emerging out of catastrophe. COVID-19’s crisis is turned, stitch by stitch, joke by joke, act by act, toward a true, progressive community of tomorrow.

About the Reviewer

Audrey Wu Clark is an Associate Professor of English at the United States Naval Academy. Her work focuses on Asian American literature, African American literature, critical race theory, and twentieth-century American literature.

0