The Book

How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019)

The Author(s)

Daniel Immerwahr

Editor's Note

Editor’s note: Daniel Immerwahr has written a reply to this review, posted here.

Since its publication in early 2019 Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States has received unusual amounts and intensities of praise and criticism. Criticism has come from some general readers—especially those who view the book as insufficiently or too lefty—and from some of Immerwahr’s fellow academics. These include historians Paul A. Kramer (commenting on a 2016 précis of the book), Anders Stephanson, and Christian Appy, and sociologist Stuart Schrader. Historian Patrick Iber tilts toward praise of the book (hereafter HTH) as do the four reviewers in a Society for the History of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR) roundtable: Thomas Bender, Emily Conroy-Krutz, David Milne, and Odd Arne Westad. With the exception of Iber’s reference to Kramer, none of these analyses engage directly with each other. As a historian of the Caribbean writing a book on labor, gender, and politics in Puerto Rico from 1937 to 1941, I aim to extend critical reactions to HTH. In so doing I will explain why I recommend other works as far better introductions to the history of places that became formal colonies of the United States, and to the history of non-incorporation itself.[1]

First, I argue that HTH obscures in multiple ways the constitutionally novel relationship of non-incorporation that extended U.S. imperial practices to direct political colonization of inhabited island groups in the aftermath of the 1898 war—the war that resulted in Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and American Samoa becoming non-incorporated territories. For Puerto Rico, HTH obscures the relationship of non-incorporation before 1952, but more glaringly after 1952 when the non-incorporated territory was re-branded as a Commonwealth (Estado Libre Asociado). Second, I argue that HTH treats the “logo” map of the lower 48 states as explanatory when it is merely symptomatic, thus obscuring the real causes of Americans’ ignorance of “formal” empire. Third, I argue that by placing Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands inside the borders of the “Greater United States,” HTH erects a historiographical barrier between them and the rest of the Caribbean. Such a barrier does not reflect realities revealed in a burgeoning scholarship of connections, border-crossing, and comparison in what some scholars conceptualize as the Greater Caribbean, a region that includes what is now the southeast United States. Instead that barrier aligns with the political walling-off of these colonies from pan-Caribbean organizations like the Association of Caribbean States. Fourth, I argue that for Puerto Rico, HTH offers a great-man episodic narrative that does not understand Puerto Rico as a post-emancipation society or engage vital historiographies of economic transformation, party politics, and non-elite agency.

Before analyzing the range of scholarly responses to HTH and then extending them, a definition of non-incorporation is in order. Neither HTH nor commentators on it offer a definition, HTH because of the author’s decision not to explore differences between different types of overseas possessions, the commentators because they either follow HTH’s lead or focus their criticisms elsewhere.

In the Insular Cases from 1901 to 1922, the U.S. Supreme Court invented the category of non-incorporated territories in defining places acquired and possessed by the United States but not incorporated into the nation. In the first Insular Case, Downes v Bidwell, Justice Douglas White, in his concurrence with the 5-4 majority decision that tariffs could apply between the metropole and Puerto Rico without violating the Uniformity Clause of the Constitution, stated that Puerto Rico was “foreign in a  domestic sense” to the U.S. nation. From this flowed the non-incorporation doctrine that in effect amended the U.S. Constitution via Supreme Court decision rather than congressional action and state ratification. The Constitution itself makes no mention of non-incorporated territories. The non-incorporation doctrine held and still holds that: a) some territories have been acquired and possessed but not made part of or incorporated into the nation; b) it is constitutional for a republic to rule indefinitely over mostly non-white peoples without their consent; c) non-incorporated territories are not on a path to statehood; d) only the most fundamental constitutional protections apply in them. Further federal and Supreme Court decisions determined that fundamental protections do not include citizenship, jury trials, free trade with the metropolitan United States, or federal voting rights and representation. Any branch of the federal/imperial government can veto territorial legislation. In 1917, by which time most of the Insular Cases had been decided, Congress—which determines the status of the non-incorporated territories and their peoples under the Constitution’s Territorial Clause (Article IV, Section 3)—made Puerto Ricans and their descendants into statutory U.S. citizens without putting Puerto Rico on a path to statehood. Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa have been non-incorporated territories since the very early twentieth century, the U.S. Virgin Islands from 1917, and the Northern Mariana Islands since 1986. The Philippines was a non-incorporated territory from 1901 to 1946, and is the only non-incorporated territory to have exited that status.

domestic sense” to the U.S. nation. From this flowed the non-incorporation doctrine that in effect amended the U.S. Constitution via Supreme Court decision rather than congressional action and state ratification. The Constitution itself makes no mention of non-incorporated territories. The non-incorporation doctrine held and still holds that: a) some territories have been acquired and possessed but not made part of or incorporated into the nation; b) it is constitutional for a republic to rule indefinitely over mostly non-white peoples without their consent; c) non-incorporated territories are not on a path to statehood; d) only the most fundamental constitutional protections apply in them. Further federal and Supreme Court decisions determined that fundamental protections do not include citizenship, jury trials, free trade with the metropolitan United States, or federal voting rights and representation. Any branch of the federal/imperial government can veto territorial legislation. In 1917, by which time most of the Insular Cases had been decided, Congress—which determines the status of the non-incorporated territories and their peoples under the Constitution’s Territorial Clause (Article IV, Section 3)—made Puerto Ricans and their descendants into statutory U.S. citizens without putting Puerto Rico on a path to statehood. Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa have been non-incorporated territories since the very early twentieth century, the U.S. Virgin Islands from 1917, and the Northern Mariana Islands since 1986. The Philippines was a non-incorporated territory from 1901 to 1946, and is the only non-incorporated territory to have exited that status.

Critical Analyses so far

Critical analyses of Immerwahr’s Bernath Lecture précis and HTH range from Kramer’s full-throated denunciation and Appy’s sharp critique, to Stephanson’s and Schrader’s partially complimentary but still strongly critical views, to Iber’s mildly critical defense, and finally to the SHAFR roundtable’s robust praise sprinkled with just a few “quibbles.” In this section I begin with HTH’s strongest supporters and point out how criticisms of him mount and connect as we move along the range back toward Kramer, a historian of the United States who has researched US colonialism in the Philippines and the vast historiography of U.S. empire. Notably, none but Kramer make any substantive analysis of Puerto Rico, its historiography, or how Immerwahr included Puerto Rico in his Bernath Lecture and HTH.

The January 2020 SHAFR roundtable reviewers praise HTH for offering an original, convincing, and deeply-researched argument that the United States built a territorial empire and then retreated from it, backed up by engagingly narrated evidence on a sweeping global scale, about both imperialists and the colonized, resulting in brilliant synthesis of vast academic historiographies that otherwise would be unknown to the general public.[2] The quibbles take the form of requests for more: Bender wants more on the anti-imperialists of the early twentieth century, Conroy-Krutz on nineteenth-century continental empire building, and Westad a more comparative, less detailed narrative. While Westad welcomes HTH for showing that U.S. empire was not just informal, he also would have liked more about U.S. financial capitalism as a form of empire. The roundtable includes no commentary on U.S. formal colonies in the Caribbean beyond repetition of some of HTH’s basic points, which is perhaps not entirely surprising given that none of the reviewers are specialists on the region or U.S.-Latin America relations.

Iber defended HTH from Kramer’s critique immediately upon its publication, on the grounds that the book is aimed at a popular audience that does not know existing historiographies of Puerto Rico and other formal U.S. colonies, a point that Conroy-Krutz has echoed.[3] But Iber agrees with what he takes to be Kramer’s view that by defining U.S. empire narrowly as formal territorial empire, HTH left out both economic and military aspects of U.S. informal empire. Like Westad, Iber wants more added. He states early on that Puerto Rico’s colonial status is “widely recognized if not deeply considered,” and then proceeds to give it minimal, factually incorrect consideration, despite his Latin Americanist graduate training.[4]

Schrader welcomes how HTH makes empire central to U.S. history and to the erosion of republicanism but expounds a robust critique of its silence about the “imperial logic of capitalism,” aka dollar imperialism.[5] He is particularly critical of the post-World War Two part of HTH: “The second half of the book left me with the sense that Immerwahr obscures the United States’s true imperial dynamics by retaining the outdated analytical salience of territory.” He thus goes further than Iber or Westad, arguing that focusing narrowly on formal empire distorts and, in fact, hides the full workings of U.S. empire. Schrader also wants HTH to give more specifics on how powerful actors have hidden empire, giving as his own example the seating of financial empire in the U.S. Treasury Department and Federal Reserve. Schrader barely mentions U.S. formal colonies in the Caribbean, and his argument that Puerto Rico “is perhaps the most glaring example of ongoing colonialism” is undercut by his U.S.-centric dismissal of territory as no longer salient to U.S. imperial practice after World War Two. Like Iber, he acknowledges Puerto Rico more in theory than practice.

Stephanson’s critique focuses on the second half of HTH but extends to the first half, which he views as lacking any argument and being a purely descriptive narrative of “episodes in the life of empire” which others have written about before—even the chapter on guano islands that others view as original.[6] Yet he accepts Immerwahr’s disinterest in causality in the first half, views HTH as a successful popular history, and deems the book’s material on the 1910s-1930s period of “relative neglect” and imperial experimentation as “especially good,” pointing entirely to examples that portray colonized Puerto Ricans mainly as victims.[7] Stephanson argues that the second half has “altogether too simple [a] thesis” of imperial retreat, which he deems “unpersuasive,” noting in passing that “Puerto Rico remained.” Here he emphasizes not so much dollar imperialism as the related “geopolitics of alliances dominated by the hegemonic United States in the name of the Cold War … ‘national security’ and anti-communism.”[8] Westad and Iber see HTH as simply neglecting to include informal empire, while Schrader sees him as obscuring the true dynamics of empire by doing so. Stephanson criticizes HTH’s conception of empire as not just incomplete or distorting but as inelastic, unable to accommodate the prevailing imperial practices of the Cold War period—and thus presumably earlier forms of “informal” empire as well. Puerto Rico exists in his analysis mainly to show that some descriptive narrative works well.

Appy extends and redirects Stephanson’s critique.[9] Like Stephanson he points to the book’s “definitional constraints,” arguing that HTH’s narrow definition of empire and enthusiasm for technical innovation as explanatory inhibit “our ability to formulate a truly global analysis of American power” and challenges to it.[10] But he does not focus on the formal/informal empire issue. Instead, he excoriates Immerwahr’s decision to simply describe the shape of U.S. empire rather than explain how empire began or has been maintained, or to assess its character or appalling consequences. This emphasis on geographical description is what perpetuates the hiddenness of U.S. empire for Appy. He also takes on Immerwahr’s writing style. Denouncing HTH’s “gee-whiz” tone, he argues that a historian uninterested in the “motives, conduct, and consequences of U.S. imperialism” has no business presenting history as a set of “fun facts” or shocking anecdotes.[11] Unlike Stephanson, he cuts Immerwahr no slack for ignoring causality in favor of description in the first half of the book. Appy does praise HTH’s chapter on nineteenth-century guano island acquisition, though he argues that it should be paired with a chapter on the war against Mexico and transformation of northern Mexican states into U.S. territories awaiting statehood, something that Conroy-Krutz also wants added to the narrative.[12] Nor is Appy particularly impressed by descriptions of medical abuse in Puerto Rico, calling them “important and shocking, but hardly exceptional” in the larger field of U.S. domestic racism and imperialism writ large.[13] He has no particular interest in Puerto Rico, and misses HTH’s point that the 1856 National Guano Act was a precedent for the vitally important Insular Cases beginning in 1901.[14]

Almost a year before Appy, Kramer published a thorough rebuttal of Immerwahr’s SHAFR Bernath Lecture, which in 2016 had previewed the main arguments of HTH.[15] Iber reads Kramer as calling for attention to informal as well as informal empire, but Kramer is calling for a conceptual shift away from that binary. He praises “historical scholarship on U.S. overseas colonialism in the twentieth century” for revealing both the “spectrum of sovereignties that lay between “dependency” and “independence”… and the profound reliance of U.S. commercial expansion and military projection … upon U.S. overseas colonies.”[16] While he does criticize the Bernath Lecture for focusing only on formal colonies, elsewhere he has called to task those who focus on “informal empire” for “reducing “formal” colonialism to a strict function of “informal empire,”” for “abstract[ing] the relationship between capitalist social relations and state power,” and for being unskilled in social and cultural historical methodologies and instead “foreground[ing] elite, metropolitan actors” and “privileging agents of the state.”[17] For Kramer, undoing that conceptual binary will facilitate non-exceptionalist comparisons of the United States with other empires.

Kramer is the only critic of Immerwahr’s project to demonstrate broad familiarity with and genuine interest in the flourishing scholarship on the non-incorporated territories—and of the remaining ones, especially Puerto Rico. No other reviewer mounts a critique of that project’s engagement with key historiographies and its historiographical positioning and claims; its conceptualization of the U.S. metropole’s relationship to various types of colonized territory; and its intellectual entrapment in a “nationalist transnationalist” methodological framework. For Kramer a “more cosmopolitan history of the United States” that fails to open “out onto or [engage] with other sets of inquiries” just means “enlarging U.S. nationalist histories” with a “We are the World” sensibility. Immerwahr, in Kramer’s view, is a historian positioned neither “‘outside’ of U.S. history” nor “in the rich interstices between the United States and the rest of the world.”[18] Indeed, Iber notes that HTH is “written from the mainland out, rather than the colonies in.” Kramer questions both Immerwahr’s knowledge of the recent historiography of Puerto Rico and his narrative deployment of Puerto Rican Nationalist Party leader Pedro Albizu Campos. Immerwahr sidestepped in his response by characterizing Kramer’s serious point about historiographical expertise as “waving our bibliographies in the air” and making no mention of Albizu.[19] HTH does not address these points either.

Ultimately Kramer wants historians of U.S. empire—both those rooted in Caribbean, Latin American, Pacific island or Asian history and those rooted in varieties of U.S. history—to practice post-nationalist transnationalism, in which the questions asked and concepts employed come from a community of inquiry that is truly global. To study the non-incorporated territory end of the “spectrum of sovereignties” within the practices of U.S. empire in this way means several things. First, it means paying close attention to how historians and legal scholars across unequally powerful sectors of the academy have conceptualized the relation of non-incorporation between the United States as a nation state/imperial metropole and those places that became non-incorporated territories, and what lines of inquiry they have pursued. It means understanding the histories of places that became non-incorporated territories before U.S. invasion, not least to better understand the reactions of all social sectors and political actors to non-incorporation, including non-elites. It means seeing formal legal/constitutional colonization rooted in the power of the metropolitan state, a state that also facilitates flows of U.S. capital and labor around the world, as well as in and out of the metropole, by military means if necessary. And it means analyzing the U.S. imperial nation-state’s practices of non-incorporation in comparative perspective without any assumptions of U.S. exceptionalism. Finally, it means understanding non-incorporated territories as embedded in their own geographic regions, connected to their neighbors as well as the imperial metropole, and as part of those regions’ historiographies.

How to Hide Non-Incorporation

Kramer argues that the Bernath Lecture homogenized “radically different political spaces and modes of empire-building” into a “unified exception to reified, “regular” U.S. space,” thus “flattening … a spectrum of sovereignties into a polarized dichotomy.”[20] But neither he nor any other reviewer, whether delivering praise or criticism, uses or defines the terms non-incorporation or non-incorporated territory. Bender comes closest: “There was no conception of exterior American space in the constitution, and certainly nothing about colonies,” he writes, before noting HTH’s connection of the Guano Island Act to the later Insular Cases.[21] The Bernath Lecture and HTH hide non-incorporation in four ways. First, they devote a miniscule amount of time and space explaining it. Second, they pervasively lump non-incorporated territories together with incorporated territories and leased military areas and refer to all of them as “territories.” Third, they collapse the distinct relationship of non-incorporation via the concept of “the Greater United States”. Fourth, they gloss over the ongoing existence of non-incorporated territories after World War Two. Bizarrely for a book about U.S. territorial empire, non-incorporation is simply not an organizing principle of HTH.

The Bernath Lecture briefly argues that the early Insular cases “concluded that the bulk of the territories were “unincorporated” into the political body of the United States” but without offering a clear definition of non-incorporation. Moreoever, the Lecture refers to “the territories” as not only the four that had become non-incorporated territories by 1917 but also to Hawai‘i and Alaska, which were always incorporated territories on a path to statehood, and leased areas like Guantánamo. The claim that the “bulk” of this heterogeneous group were “unincorporated” is misleading and obscures the specific extent and meaning of non-incorporation. Further, the Bernath Lecture soon after interprets the Insular Cases as leading to a “reassertion of an understanding of the United States as a nation-state” when in fact they asserted quite plainly that the United States was now an imperial metropole in relation to non-incorporated territories.[22] HTH itself buries a brief mention of non-incorporation in chapter five, again without a full definition, but now including a sentence about Alaska and Hawai‘i being incorporated.[23] Again the book’s ongoing homogenizing of non-incorporated and incorporated territories obscures the specific extent and meaning of non-incorporation without offering a rationale for doing so. A reader interested in non-incorporation will not find the term in HTH’s index.

HTH cites some of the best sources by metropole-based scholars for understanding the non-incorporation doctrine, but Immerwahr does not seem to have absorbed the radical implications of their arguments and evidence.[24] HTH does not engage works by Puerto Rican legal scholars Efrén Rivera Ramos, law professor and former Dean of the Law School at the University of Puerto Rico flagship campus in Río Piedras; Judge José A. Cabranes, presiding judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review and member of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals since 1994; and Judge Juan R. Torruella, a member of the First Circuit Court of Appeals since 1984.[25] Finally, in chapter four HTH implies that colonized people were absent in immediate post-1898 debates over what to do with the new insular possessions, something disproved in the case of Puerto Rico by law professor and legal historian Sam Erman’s 2010 dissertation, now published as a monograph, and by earlier Puerto Rican historians.[26]

In his response to Kramer, Immerwahr argued that he proposed “to define the United States broadly.”[27] This conceptual move collapses the colonial relationship of non-incorporation into a concept of “the Greater United States” in which non-incorporated territories become “part of the country … part of its history” and are grouped with incorporated territories and areas leased mainly for military purposes.[28] Immerwahr defends the use of “the Greater United States” as a “clarifying past concept” from the early twentieth century because it counters “those who would deny or minimize the United States’ territorial empire”.[29] But combatting such denialism does not require “understanding Puerto Rico to be part of the United States” or rejecting the “logic of the Insular Cases”.[30] Both such conceptual moves actually make it harder to see and understand the relationship of non-incorporation, which is to say that of colonization.

The whole point of encoding colonial difference in the non-incorporation doctrine was and is to hold non-incorporated territories and their majority non-white peoples separate from the nation, so that they are not part of it. Including them conceptually as “part of” the national history obscures this past and present reality and perpetuates the miseducation of history students and historians. By collapsing non-incorporation, HTH works against full recognition and explanation of Puerto Rico’s colonial relationship with the United States, but also against recognition that Puerto Rico has never only been a place subject to Spanish or U.S. imperial power. Historians must hold in tension Puerto Rico’s simultaneous status as a unique creolizing multi-racial society since the 1510s, home and often patria (homeland) to millions, and its status as a colony ceded by a fading metropole to a rising one. Puerto Rico cannot be subsumed within U.S. geography, history, or historiography, even as it is relevant to all three.[31] “Foreign in a domestic sense,” post-1898 Puerto Rico, its history, and its historiography are at once inside and outside of U.S. history and historiography. Historians cannot make non-incorporation disappear with the wave of a pen; if it ends at all it will likely be because mass popular pressure forces Congress to agree to binding referenda or to pass legislation directly.

Puerto Rico largely disappears from HTH after it was re-labeled a Commonwealth (Estado Libre Asociado) in 1952 in a complex and contested process. HTH does acknowledge that “the actual lines of authority didn’t change” in 1952, but could more clearly state that there was no constitutional change in relationship and could point out that despite U.S. pressure only a 43.4 per cent plurality agreed at the UN in 1953 that Puerto Rico had been decolonized. A few pages later HTH shifts to arguing that Commonwealth status was “nebulous”—it would be more accurate to say that the label was deliberately misleading.[32] Overall HTH soft-pedals Commonwealth/ELA as re-branded non-incorporation/colonialism; together with the absence of a narrative of Puerto Rico’s post-1952 history this is clearly aimed at shoring up the implausible argument for significant post-World War Two U.S. decolonization. Again, since 1946, one non-incorporated territory has become an independent nation, while a UN trust territory has become a non-incorporated territory. A historian with a clear understanding of how little changed in Puerto Rico in 1952 would be unlikely to stumble into a confusing statement like this during a radio interview: after World War Two “even in Puerto Rico, which still remains a territory, there was a constitutional change such that it was a commonwealth now.”[33] There was no constitutional change; it is a non-incorporated territory that goes by the label Commonwealth/Estado Libre Asociado.

HTH and the Bernath Lecture thus hide non-incorporation by insufficiently defining it, by grouping incorporated territories, non-incorporated territories and leased military areas together, by including that homogenized group as part of the nation and its history via the “Greater United States” concept, and by almost excluding post-World War Two histories of the remaining non-incorporated territories.

Hiding behind the Logo Map

HTH also hides the causes of the exclusion of U.S. “formal” empire (or, more specifically, non-incorporated territories) from textbook and survey narratives of U.S. history. It does this by attributing that exclusion to the power of the logo map—the outline of the lower 48 states—and to the historiographies of U.S. colonies being on library shelves where U.S. historians are not accustomed to looking. “[A]s long as we’ve got the logo map in our heads,” HTH claims, these thousands of books will seem “irrelevant”.[34] But the logo map and bad mental library maps are just symptoms of the same problem, not an explanation for them. Why is the logo map still in many Americans’ heads? Why don’t more U.S. history instructors and graduate advisors direct students toward library shelves dedicated to places that became non-incorporated territories? U.S. historians did not simply “come to understand” African-American history “as central to U.S. history.”[35] It took generations of political, legal, and intellectual struggle, largely by African-Americans, to make that happen. Such struggle is objectively difficult for colonized Americans for reasons of language, legal and constitutional rights, distance from the U.S. academy, and limited metropolitan allies. More allies would be a good thing, but they should approach colonized Americans not as living in a generic “Greater United States” but as statutory citizens living in places that are non-incorporated territories, but also more than that.[36]

Sometimes students get wind that something has been kept from them, like the Michigan seventh graders HTH describes, who in 1942 complained to Rand McNally about its labeling of Hawai‘i as foreign in their school atlas, and even asked the Department of the Interior to weigh in. Rand McNally couldn’t give the girls a clear answer about how an attack on Pearl Harbor was an attack on the United States if Hawai‘i was not integral to the nation. HTH does not leverage the middle schoolers’ questioning to engage the unsettling spectacle of the world’s first post-colonial republic having become an imperial metropole, ruling over millions of people without their consent, and allowing the creation of a new constitutional doctrine without the proper amendment process in order to legitimize formal empire. Instead, it manufactures this happy ending: “Of course the seventh-graders were right. As an official clarified, Hawai‘i was, indeed, part of the United States.”[37] But what would Interior have said if the students had written about Puerto Rico, perhaps if German U-boats had attacked rapidly expanding military installations and personnel in and around San Juan in early 1942, just months after the Pearl Harbor attacks?[38] Would they have said that Puerto Rico as a non-incorporated territory was “part of the United States”? Here the homogenization of non-incorporated and incorporated territories compounds HTH’s fetishizing of maps as explanatory.

Hidden by Rand McNally, the Department of the Interior, and HTH is that the federal government does not want Americans to notice the non-incorporated territories or what their existence means about the character of the United States. The federal government and elements of the Puerto Rican political elite have invested a great deal in the illusion of decolonization via Commonwealth status. State governments, even in my home state of New York, have not included this history in K-12 social studies curricula. If most Americans learn nothing about this in school, how can they be ready to hear the truth if they somehow come across it in a bookstore, or on TV or a podcast?[39]

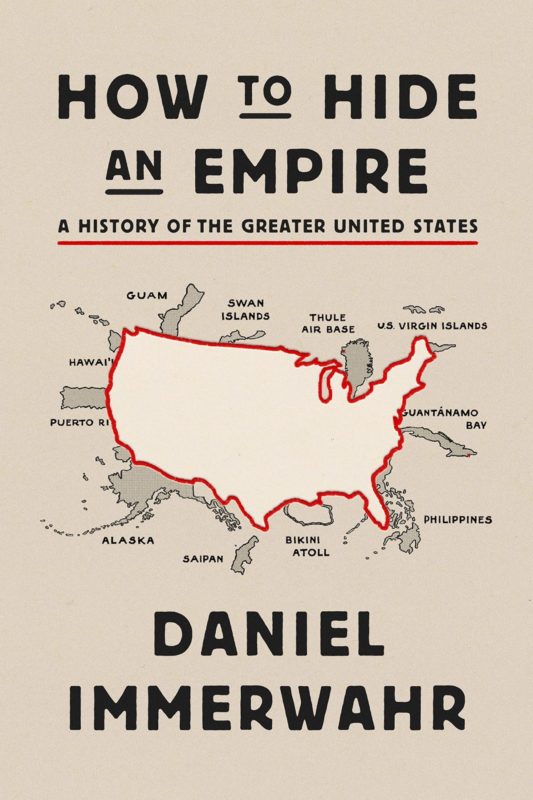

Bender praises the cover of HTH as a “brilliant image” that “immediately evokes the concept of a hidden empire.[40] It shows an outline of the continental United States covering the empire. Around the edges of the continent little projections of land stick out, and they all have labels: Guam, Swan Islands, Thule Air Base, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guantánamo, Philippines, Bikini Atoll, Saipan, Alaska, Puerto Rico, Hawai‘i. Empire could not be wholly hidden.” As a historian of the Caribbean what I see in this image is not the logo map “covering the empire.” Rather, I see not-to-scale outline maps of eleven different kinds of places controlled by the —places that have their own histories separate from U.S. colonization—removed from their correct geographic positions, detached from their neighbors, and grafted onto the outline of the metropole like puzzle pieces or pawns. Puerto Rico, for example, ends up glommed onto the coast of the Pacific Northwest, stuck between two incorporated territories that became states. If the intent was to make empire visible, the image also signals HTH’s U.S.-centricity and hiding of non-incorporation. Kramer’s point that for Immerwahr the colonies only “count once they are marked down on the “mainstream” charts may not be about the cover image, but is apt.[41]

Greater Caribbean Historiography

The concept of the Greater United States is of a bounded political unit composed of a powerful metropole and subordinate territories of various kinds that exist in relationship to that metropole. The concept of the Greater Caribbean is that of a blurry-edged ecological, economic, social, and cultural region encompassing multiple polities and peoples in dynamic interaction with each other. Geographic definitions of the Caribbean are complex and contested, but often include the Caribbean littoral from Florida around the U.S. and Mexican shores of the Gulf of Mexico, down the coast of Central America, and across the coasts of Colombia, Venezuela, and even to the Guyanas and Suriname. Stuart Schwartz in Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina stretches the Caribbean littoral north to the Chesapeake and inland in a great arc from Brownsville to Washington DC – though arguably New York City should also be included. Belize, the focus of my doctoral research and first book, styles itself “the Caribbean beat in the heart of Central America.” Both within the Caribbean archipelago and these littoral areas, collisions and blendings of indigenous, African, and European peoples and cultures have been foundational, particularly among the highly exploited laboring classes, and imperial and national powers have warred, competed, and collaborated. Echoing Sidney Mintz, Schwartz defines the region’s commonalities in terms of “the interconnected past of colonial settlements, plantation economies, and slavery, and then its subsequent history of independence, decolonization, and the hegemony of the United States.”[42] The burgeoning historiography of the Greater Caribbean is a heterogeneous grassroots project distinct from the Omohundro Institute’s call for the study of a “vast early America.” [43] Greater Caribbean historiography is not searching for any one national pre-history and pursues histories of connection and comparison across emerging and hardening national borders.

One strand of Greater Caribbean historiography that includes the United States is formed by efforts to define the three big continent-straddling nations of the region as in part Caribbean nations, in the past and present. The United States, Mexico, and Colombia all have extensive Caribbean coasts and histories of connection with other parts of the Greater Caribbean, despite dominant national narratives that marginalize these realities. Pablo Sierra Silva accelerates changes in the Mexican narrative in his work on the enslavement of Africans in early colonial Puebla and the trade in human beings through the Caribbean archipelago into New Spain. Ernesto Bassi challenges the Colombian narrative in his study of that nation’s connections across the Greater Caribbean in the Age of Revolutions. Less intentionally, Rebecca Scott highlighted the United States as an integral part of the Caribbean in her comparative study of Louisiana and Cuba, drawing on her deep knowledge of Cuban historiography to engage with historians of Louisiana and the United States.[44]

Movement has fueled connection and comparability in Greater Caribbean historiography. Scott argues that “the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico opened the way to the circulation of people, information, and ideas” and traces Cuban nationalist leader Antonio Maceo’s travels to New Orleans, Mexico, Florida, New York, Panamá, and Costa Rica.[45] Lara Putnam documents “working-class men and women who left their islands of birth at the margins of the British Empire … to seek work in ports and plantations at the leading edge of a new empire, the informal empire of the United States” in Central America—especially Panamá—the Spanish Caribbean islands, Venezuela, and eventually in New York City.[46] Their political practices in New York City and Florida have been studied by Winston James, who includes Arturo Schomburg as one of the leading Puerto Ricans within New York City’s Caribbean radicalism.[47] Indeed, the Puerto Rican diaspora pre-dated 1898. Schomburg, whose mother was from the Danish Virgin Islands and whose pan-Africanist collection forms the basis of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library, arrived in 1891. In 1889 Lola Rodríguez de Tió, a pro-independence Puerto Rican poet, feminist, and abolitionist exiled by Spain arrived, though she soon moved on to Cuba.

Rodríguez de Tió imagined Puerto Rico and Cuba as “de un pájaro las dos alas”—two wings of one bird. U.S. colonization has separated Puerto Rico from its Caribbean neighbors in painful ways. It has not been able to join key pan-Caribbean organizations, especially those for nation-states or that have included Cuba since 1959, and its people have had limited ability to travel to Cuba since 1959. Puerto Ricans have encountered other Caribbean peoples as much or more in the diaspora as in the non-incorporated territory itself, not least because Puerto Ricans have been able to seek economic stability directly in the metropole due to their status first as “Porto Rican” citizens and then as statutory U.S. citizens.

Yet Greater Caribbean historiography is tracing twentieth-century connections between Puerto Rico and other Caribbean locales, either because of or despite U.S. imperialism. José Amador studies a “fascinating set of public health circuits” fueled by U.S. military expansion and Rockefeller Foundation programs “that began in colonized settings and became increasingly, and unevenly, transnational.”[48] His work connects Puerto Rico, Cuba, the southeastern United States, and Brazil, and focuses on the movement of public health specialists. Michael Donoghue shows the movement of Puerto Ricans themselves from the non-incorporated territory and diaspora to the Panama Canal Zone through military service in the U.S. Army, including the all-Puerto Rican 65th Infantry Battalion, the only segregated Hispanic unit in U.S. Army history.[49] The Army’s ability to place these Spanish-speaking or bilingual soldiers on the border between the Zone as a leased military colony and the nation of Panamá was rooted in and even depended on the non-incorporation of Puerto Rico as a formal colony. These soldiers’ negotiation of highly complex relations among white ex-patriate Zonians, black British Caribbean canal workers, racially diverse Panamanian men and women, white and African-American fellow GIs, and the military brass was intensely challenging. Antonio Sotomayor shows how the Puerto Rican government’s negotiation of a “national” presence in international sports in the 1950s and 1960s has led to connections between Puerto Rican and other Caribbean athletes and sports leaders at the Olympics as well as regional competitions.[50] Jorge Duany—born in Cuba, raised in Panamá and Puerto Rico, based in Miami—has written extensively on Cuban and Dominican migration to Puerto Rico, New York, and the United States more broadly, and on Puerto Rican migration in both directions between the islands and the United States.[51]

HTH is conceptually at odds with Greater Caribbean historiography. In prioritizing the “Greater United States” as its unit of analysis it asks only about Puerto Rico’s relationship with the metropole, a metropole that it does not conceptualize as part of the Greater Caribbean and whose economic and military interventions in the Greater Caribbean it largely excludes. Having obscured the relationship of non-incorporation and treated the logo map as explanatory, it then divorces Puerto Rico from its Caribbean context, and produces a problematic narrative of Puerto Rico’s history under U.S. imperial rule.

How to Hide Puerto Rican Historiography

Piecing together the parts of HTH that deal principally with Puerto Rico yields a selective great-man style episodic narrative of 1898 to the 1950s that has neither synthetic nor original argument and gives a distorted impression of Puerto Rican history and historiography. First, HTH ignores pre-1898 Puerto Rican history and thus cannot trace continuities and changes across the watershed of 1898, or explain how pre-1898 dynamics shaped responses to the U.S. military occupation and then formal colonization. Second, HTH all but ignores post-1950s Puerto Rican history and so gives only fragmented glimpses of the most recent sixty years of U.S. imperial rule, sixty years during which Puerto Rico industrialized and de-industrialized, entered into permanent economic crisis and saw the diaspora grow larger than the home population, and struggled to resolve status debates. Third, it focuses largely on two dramatic themes for the 1898-1950s period: the violent tactics of and repression against Albizu and his Nationalist Party, and instances of medical discovery, treatment, experimentation and abuse—especially female sterilization and birth control experimentation. These themes are important and the instances shocking; they lend themselves to stories of heroes and villains, some of whom are named, and victims, who are not.

Below I explain how little HTH tells the reader about the history or historiography of Puerto Rican women and gender, party politics and versions of nationalism, and racism and racial identities. Many parallel commentaries could be made, for example about economic transformations within capitalism, labor conditions and organizing, and the diaspora.

Historians of women and gender in Puerto Rico have elaborated a rich historiography since the 1970s. HTH’s narrative about Puerto Rican women in relationship to U.S. imperialism ignores this body of scholarship except to highlight elite efforts to control women’s fertility, and the interest of many women in birth control. Readers come away not knowing that a women’s rights movement existed prior to 1898, that the U.S. legalized divorce in 1910 to many women’s delight, or that there was a class- and party-divided suffrage movement from the late 1910s, which succeeded for literate women in 1929 and all women in 1935.[52] Nor do they learn about the large sub-field of women’s labor history, about expanding wage labor in tobacco processing and needlework that spurred participation in the burgeoning labor movement and Socialist Party through the 1930s, and dramatic strike action and labor repression in the 1930s.[53] Nor do they learn about gendered engagement of the New Deal’s unequal treatment of Puerto Rico.[54] The fascinating gender politics of the Nationalist Party are reduced to a passing mention of Lolita Lebrón, who led the 1954 attack on Congress, while her 25 years in federal prison and subsequent decades of unarmed activism have no post-1950s narrative in which to appear.[55] Women’ participation in party politics and diasporic community-building encompass the entire late nineteenth to early twenty-first centuries.[56] More specific to the post-1950s period are their roles in industrialization, and in urban feminist, artistic, and social movements of all kinds. Their leading role in the mass movement that forced the U.S. Navy to leave Vieques, an island in the Puerto Rican archipelago, which had been used as a live bombing range since the 1940s, goes unmentioned.[57] Despite HTH’s almost exclusive focus on women as reproducers, the medicalization of childbirth from the 1940s and the renewed push for female sterilization in the 1970s go unmentioned.[58] Given the book’s popular audience it is perhaps understandable that Luisa Capetillo, the anarchist-feminist labor organizer and writer of the early twentieth century, is left out. [59] But surely the discussion of West Side Story could at least mention the iconic Rita Moreno, the only Puerto Rican with a speaking part in the 1961 film.

Historians of party politics and status debates have also produced an extensive scholarship. While the Nationalist Party has attracted understandable attention, it never had a mass base, and for various periods the dominant pro-statehood and pro-autonomy parties, and labor-based parties, have been as important. Chief among these is the Partido Popular Democrático (PPD, Popular Democratic Party), founded in 1940, dominant through 1968, and still one of the two dominant elite-run parties. By not focusing on it, HTH avoids discussion of how it sponsored post-1952 cultural nationalism as a way of legitimizing Commonwealth status, and of how the growing statehood movement and associated New Progressive Party have sought to portray statehood as no threat to Puerto Rican culture and identity.[60] Such discussions may lack the drama and caché of political nationalism, but they are crucial for understanding political life in the non-incorporated territory and how U.S. imperialism has shaped the political field of action and political identities. The vast majority of Puerto Rican have exercised agency within the imperial system more than against it.[61]

HTH rightly points out the racist basis of territorial empire and even the Insular Cases, but does not engage historiography and other scholarship on the changing dynamics of racism and racial identities in Puerto Rico itself since the sixteenth century, or even the late nineteenth century, or how these shaped various responses to U.S. imperial rule. This scholarship connects Puerto Rico’s longue durée under Spanish rule as a multiracial creolizing society with slavery to post-1898 history and the present. Three key works—by Eileen Findlay, Ileana Rodríguez Silva, and Isar Godreau—encompass the post-emancipation period beginning in 1873, and end at various points in the twentieth century.[62] They thus treat 1898 as an important turning point, but not the only one. Anthropologists like Godreau, Duany and Hilda Lloréns bring histories of race in Puerto Rico up to the present and focus on how U.S. systems of racism have interacted with Puerto Rico’s, both in Puerto Rico and the diaspora. Because of HTH’s narrow time-frame when it comes to Puerto Rico, it is poorly positioned to engage this field of scholarship, even if it had a more sustained interest in issues of race. A powerful entry point into this scholarship could have been HTH’s description of the clash between Albizu’s racial identity and the Army board of physicians’ conclusion after a physical exam that he belonged in an African-American unit in World War One.[63] Indeed, Puerto Ricans and metropolitan Americans have struggled to understand each other’s versions of racism and racial identities for well over a century, on a very uneven field of power.

Kramer sharply criticized Immerwahr’s narrative deployment of Albizu in his Bernath Lecture. “At first glance, his choice to begin the essay with a Puerto Rican nationalist seems to suggest that he takes Puerto Rican history, culture, and agency seriously,” but Kramer argues that Immerwahr then told a very U.S.-centric story about Albizu.[64] This pattern continues in HTH, which makes no mention of his pre-1898 childhood, when his Afro-descended maternal aunt was raising him, or of his crucial 1927-30 trip to the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, Mexico, and Peru to build Greater Caribbean and pan-American support for Puerto Rican independence. HTH weaves Albizu’s biography across several chapters, focusing on his time at Harvard and in the U.S. Army, as well as his reactions to medical abuse and his advocacy of Nationalist armed rebellion. But it ignores the painful final incarcerated decade of Albizu’s life from 1955-65, which would work against arguments of post-World War Two U.S. decolonization broadly and in Puerto Rico. To hide his last years and the incarceration of Nationalists in Puerto Rico and federal prisons is to hide not only ongoing U.S. “formal” imperialism, but its most brutal face. Whatever critique one might have of Albizu—and serious critiques exist—he is not a man to be reduced to a narrative prop. Albizu would have objected to being called a “domestic” anti-imperialist, an adjective made possible by HTH’s “Greater United States” conceptual domestication of the non-incorporated territories. He would also have disagreed profoundly with HTH’s concluding argument that “empire is not only a pejorative. It’s also a way of describing a country that for good or bad, has outposts and colonies. In this sense, empire is not about a country’s character, but its shape.”[65] For Albizu empire was always a pejorative, always morally indefensible, because it violated republican principles and denied national self-determination to peoples who had seen the United States as a post-colonial pioneer. U.S. imperial rule in the five remaining non-incorporated territories continues to effect such violation and denial. Anger about the federal government’s treatment of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria gets us nowhere if it is not linked to an accurate analysis of the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States from 1898 to today.

Conclusion

Any of the works cited above on non-incorporation, the Greater Caribbean, and Puerto Rico are worth the time of U.S. historians. For those lucky enough to work in institutions where courses on Puerto Rican history are offered, U.S. historians can take the time to join the students and do the reading. I highly recommend beginning self-(re)education with Cesar Ayala and Rafael Bernabe’s narrative Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History Since 1898 and the anthology Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State, co-edited by Francisco Scarano, a historian of Puerto Rico, and Alfred McCoy, a historian of the Philippines.[66] By bringing together specialists on those two places, Colonial Crucible achieves what no single-authored volume can do with regard to the non-incorporated territories. Their historiographies are simply too large for any one person to master and synthesize, even if that someone is already rooted in the historiography of one place that became a non-incorporated territory, and of the region to which that place belongs. It will take much listening, dialogue, and many voices to make past and present imperial practices central to U.S. history K-12 curricula, college surveys, graduate training, and textbooks, and to steer students of U.S. history toward the library shelves where many of us have been all along. For all the reasons that I have laid out above, HTH is not a positive contribution to such dialogue, and I urge U.S. historians who are trying to transform their thinking, teaching, and research not to be guided by it.

[1] My book manuscript is titled “Fight for an Impossible Progress: Workers, New Deal Labor Reform, and Populism in Puerto Rico, 1937-1941.” My work on U.S. colonialism in Puerto Rico and on colonialism and decolonization in the Caribbean more broadly includes: “Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage: The Struggle over the Fair Labor Standards Act in Puerto Rico, 1938-1941,” Journal of American History 104:3 (December 2017), 656-680; “Towards Decolonization: Impulses, Processes, and Consequences,” 475-489 in Stephan Palmié and Francisco Scarano, eds., The Caribbean: An Illustrated History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); From Colony to Nation: Women Activists and the Gendering of Politics in Belize, 1912-1982 (Lincoln: Nebraska, 2007); “Citizens vs. Clients: Workingwomen and Colonial Reform in Puerto Rico and Belize, 1932-1945,” Journal of Latin American Studies 35:2 (May 2003): 279-310.

[2] Carol Chin, Thomas Bender, Emily Conroy-Krutz, David Milne, Odd Arne Westad, and Daniel Immerwahr, “A Roundtable on Daniel Immerwahr, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States,” Passport: SHAFR Review 50:3 (January 2020): 8-16.

[3] Patrick Iber, “Off the Map: How the United States Reinvented Empire,” New Republic Feb. 12, 2019 (https://newrepublic.com/article/153038/how-america-reinvented-empire-review-daniel-immerwahr)

[4] Iber claims that Puerto Rico got civilian rule after World War Two; in fact several pre-1945 governors were civilians and the last one who came from the military left office in 1939. He also implies that Puerto Rico was not a colony by the 1960s; in fact, being labeled a Commonwealth (Estado Libre Asociado) since 1952 has not ended Puerto Rico’s non-incorporated territory status.

[5] Stuart Schrader, “Imperialism after Empire,” Boston Review: A Political and Literary Forum, March 29, 2019 (http://bostonreview.net/war-security/stuart-schrader-imperialism-after-empire)

[6] Anders Stephanson, “Neo-Impressionist Hegemon?” New Left Review 118 (July/August 2019): 150-58.

[7] Stephanson, 153-54.

[8] Stephanson, 155-57.

[9] Christian G. Appy, “Empire Lite,” Catalyst: A Journal of Theory and Strategy 3:3 (Fall 2019): 133-53. (https://catalyst-journal.com/vol3/no3/empire-lite)

[10] Appy, 135.

[11] Appy, 151-52.

[12] Appy, 138.

[13] Appy, 144.

[14] The National Guano Act of 1856 authorized citizens of the United States to take possession of and exploit unclaimed islands, reefs, and atolls containing guano deposits. The islands had to be uninhabited and not within the jurisdiction of another government. The act specifically referred to such islands as possessions of the United States.

[15] Paul A. Kramer, “How Not to Write the History of U.S. Empire,” Diplomatic History 42: 5 (2018): 911-31.

[16] Kramer, “How Not to Write,” 911.

[17] Paul A. Kramer, “Power and Connection: Imperial Histories of the United States in the World,” American Historical Review (Dec. 2011), 1374-75.

[18] Kramer, “How Not to Write,” 921-22.

[19] Daniel Immerwahr, “Writing the History of the Greater United States: A Reply to Paul Kramer,” Diplomatic History 43:2 (2019), 402.

[20] Kramer, “How Not to Write,” 918.

[21] Chin, Bender, et al, 8.

[22] Daniel Immerwahr, “The Greater United States: Territory and Empire in U.S. History,” Diplomatic History 40:3 (2016), 381.

[23] Immerwahr, HTH, 85-87.

[24] Christina Duffy Burnett and Burke Marshall, eds., Foreign in a Domestic Sense: Puerto Rico, American Expansion, and the Constitution (Duke 2001); Bartholomew Sparrow, The Insular Cases and the Emergence of American Empire (Kansas 2006); and Gerald L. Neuman and Tomiko Brown-Nagin, eds., Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of American Empire (Harvard Law School, 2015).

[25] Efrén Rivera Ramos, The Legal Construction of Identity: The Judicial and Social Legacy of American Colonialism in Puerto Rico (Washington DC: American Psychological Association, 2001); José Cabranes, Citizenship and the American Empire: Notes on the Legislative History of the United States Citizenship of Puerto Ricans (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979); Juan R. Torruella, The Supreme Court and Puerto Rico: The Doctrine of Separate and Unequal (UPR 1988) and Judge Torruella’s many excellent articles.

[26] Sam Erman, Almost Citizens: Puerto Rico, the U.S. Constitution, and Empire (Cambridge 2019); Arturo Morales Carrión, Puerto Rico: A Political and Cultural History (Norton 1983).

[27] Immerwahr, “Writing the History,” 398.

[28] Immerwahr, “The Greater United States,” 277.

[29] Immerwahr, “Writing the History,” 400.

[30] Immerwahr, “Writing the History,” 398 and “The Greater United States,” 382.

[31] Macpherson, “Birth of the U.S. Colonial Minimum Wage,” 658.

[32] Immerwahr, HTH, 257 and 262.

[33] “The History of American Imperialism, From Bloody Conquest to Bird Poop,” Fresh Air, February 18, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/02/18/694700303/the-history-of-american-imperialism-from-bloody-conquest-to-bird-poop

[34] Immerwahr, HTH, 8-9 and 15.

[35] Immerwahr, “The Greater United States,” 376.

[36] American Samoans do not yet have statutory birthright citizenship. A late 2019 court decision that would pave the way for this has been put on hold by the very judge who issued it pending the federal government’s appeal. See: https://www.npr.org/2019/12/13/787978353/american-samoans-citizenship-status-still-in-limbo-after-judge-issues-stay Not all American Samoans want U.S. citizenship: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/02/not-everyone-born-in-samoa-wants-u-s-citizenship/

[37] Immerwahr, HTH, 12.

[38] https://uboat.net/maps/caribbean.htm

[39] John Oliver, Last Week Tonight, March 8, 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CesHr99ezWE

[40] For an image of the cover map see: https://www.ecosia.org/images?q=How+to+Hide+an+Empire#id=4DAA21AF60CAAA044BE9A909837C923DBDD18A16

[41] Kramer, “How not to Write,” 923.

[42] Stuart Schwartz, Sea of Storms: A History of Hurricanes in the Greater Caribbean from Columbus to Katrina (Princeton 2015), xiv-xv.

[43] Karin Wulf, “Vast Early America: Three Simple Worlds for a Complex Reality,” February 6, 2019 (https://blog.oieahc.wm.edu/vast-early-america-three-simple-words/)

[44] Ernesto Bassi, An Aqueous Territory: Sailor Geographies and New Granada’s Transimperial Greater Caribbean World (Duke 2016); Pablo Sierra Silva, Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Ángeles, 1531-1706 (Cambridge 2019); Rebecca Scott, Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery (Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 2005).

[45] Scott, 2-3.

[46] Lara Putnam, Radical Moves: Caribbean Migrants and the Politics of Race in the Jazz Age (UNC 2013).

[47] Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century America (Verso, 1999/2019)

[48] José Amador, Medicine and Nation-building in the Americas, 1890-1940 (Vanderbilt, 2015), 2.

[49] Michael Donoghue, Borderland on the Isthmus: Race, Culture, and the Struggle for the Canal Zone (Duke 2014)

[50] Antonio Sotomayor, The Sovereign Colony: Olympic Sport, National Identity, and International Politics in Puerto Rico (Lincoln: Nebraska, 2016).

[51] Two examples of Duany’s work are: The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States (UNC 2002) and Blurred Borders: Transnational Migration between the Hispanic Caribbean and the United States (UNC 2011).

[52] Eileen J. Suárez Findlay, Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870-1920 (Duke 1999); Eileen J. Findlay, “Love in the tropics: marriage, divorce, and the construction of benevolent colonialism in Puerto Rico, 1898-1910,” in Gilbert M. Joseph, Catherine C. LeGrand, and Ricardo D. Salvatore, eds. Close encounters of empire : writing the cultural history of U.S.-Latin American relations (Duke 1998); María de Fátima Barceló Miller. La lucha por el sufragio femenino en Puerto Rico, 1896-1935 (Rio Piedras: CIS/Ediciones Huracán, 1997).

[53] The pioneering works of Blanca Silvestrini and María del Carmen Baerga are vital to this historiography.

[54] Emma Amador, “‘Women Ask Relief for Puerto Ricans’: Territorial Citizenship, the Social Security Act, and Puerto Rican Communities, 1933-1939,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 13:3-4 (Dec. 2016), 105-29.

[55] Olga Jiménez de Wagenheim, Nationalist Heroines: Puerto Rican Women History Forgot (New Brunswick NJ: Markus Wiener, 2016).

[56] Virginia Sanchez Korrol, From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City (California 1994)

[57] Katherine T. McCaffrey, “Social Struggle against the U.S. Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico: Two Movements in History,” Latin American Perspectives 33:1 (2006), 83-101

[58] Isabel Córdova, Pushing in Silence: Modernizing Puerto Rico and the Medicalization of Childbirth (Texas, 2018)

[59] Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, “The Historiography of Luisa Capetillo,” in Luisa Capetillo, A Nation of Women: An Early Feminist Speaks Out/Mi opinion: sobre las libertades, derechos, y deberes de la mujer, ed. Félix V. Matos Rodríguez FVMR (Arte Público, 2004).

[60] Arlene Dávila, Sponsored Identities: Cultural Politics in Puerto Rico (Temple 1997)

[61] María Acosta Cruz, Dream Nation: Puerto Rican Culture and the Fictions of Independence (Rutgers 2014)

[62] Findlay, Imposing Decency; Ileana Rodríguez Silva, Silencing Race: Disentangling Race, Colonialism, and National Identities in Puerto Rico (Palgrave Macmillan 2012); Isar Godreau, Scripts of Blackness: Race, Cultural Nationalism, and U.S. Colonialism in Puerto Rico (Illinois, 2015).

[63] Immerwahr, HTH, 119.

[64] Kramer, “Now Not to Write,” 922-23.

[65] Immerwahr, HTH, 121, 400.

[66] Cesar Ayala and Rafael Bernabe, Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History since 1898 (UNC 2007); Scarano and McCoy, eds., Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State (Wisconsin 2009). For U.S. historians who wish to make empire as central to their teaching as race, class, or gender, Jorge Duany’s Puerto Rico: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford 2017) could be assigned to students.

About the Reviewer

Anne S. Macpherson is Professor and Chair of History at SUNY Brockport, near Rochester NY. She is author of From Colony to Nation: Women Activists and the Gendering of Politics in Belize, 1912-1982, co-editor with Karin Alejandra Rosemblatt and Nancy Appelbaum of Race and Nation in Modern Latin America, editor of Backtalking Belize: Speeches and Writings of Assad Shoman, 1963-1995, and author of several essays on nineteenth- and twentieth-century Caribbean, Puerto Rican, and Belizean history.

12 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Such a thoughtful and substantive discussion in this essay. I would like to invite our readers into a discussion of how historians in recent years have worked to transform understanding of the “US in the world”–to use a field designation that is relatively neutral in tone. What have been the objectives of US historians working to retell the story of the United States in new ways? What are our responsibilities to other historiographies? What are the productive lessons to be drawn from what historians of (often from) the other parts of the world the US has touched (everywhere!)? Can a story centered on US society be done in a way that is not chauvinist on some deeper level? From the perspective of understanding US institutions and lifeways, what are the most important lessons to be drawn from looking at US interactions with other societies?

One of the things I learned from this review is that the danger of well-intended US historians trying to go transnational is that they can end up oddly reproducing the very imperialism they seek to critique!

More than that, however, I find the concept of different regionalities a promising approach for cutting against the nation-state. The Greater Caribbean strikes me as a very promising framework for considering histories that don’t discount the power of the US in the region but also shift from the colonial-anticolonial dichotomy to a sense of dense layers of interaction among multiple historical actors and circulating forces and ideas. This is not to discount the often-obscene power of the imperial metropole against the colonial margins, but rather to catch more accurately how actually existing imperialism has and continues to function. Indeed, perhaps multiple, dynamic, overlapping regionalist approaches could even be employed more sensitively *within* histories of the US nation as traditionally conceived. We have South, East, and Midwest, but every time I drive along the Ohio River, I wonder exactly which part of the US I’m in. Here, there, everywhere a borderlands? Whether it be an archipelago of ports, a riverine network, a desert, a travel route, a waterway, a sea, an ocean.

The other issue with this book, to me, worth debating more fully has to do with something Macpherson only glancingly touches: the matter of audience, or better put, intended audience. This book seeks to respond to the recent call for a more publicly oriented, “accessible” mode of historical writing for the “general reader” (whoever the heck that is!). But in its particular approach it raises if not an imperial flag, than a rather imperious one. Which is to say I am wondering if How To Hide an Empire employs a rather outmoded approach to speaking historically to public audiences. It masks what in fact is a rather smug, condescending attitude toward the “general reader” within a supposedly more simplified, accessible “general audience” approach to writing history. It strives to appeal to the broader public, with a smile on its face, when in fact it looks down upon them from on high, not believing those readers can handle the actual complexities of the historical stories at hand.

I wonder if in fact that broader market of readers (the ones browsing in the always-invoked airport bookstore—and that gives away that it is more of a market than a public here) hungers precisely for access to the complexity of historical truth Macpherson presents here in response to the book. Maybe the faux-populist popular history turn of which this book is emblematic is a canard. If so, then the great challenge would be to be able to explain cogently, clearly, compellingly the texture of imperial contestation and consolidation in a place like Puerto Rico rather than cherry picking stories from that part of the world to confirm a master narrative of worldwide US empire as a one-size-fits-all imperium. No small task that, but a worthy, democratic, and perhaps even anti-imperial one to pursue.

I’ve sent USIH a response to Macpherson’s thoughtful piece, which I presume they’ll post shortly. But I wanted to reply to this issue of popular history, Michael. I wrote the book with the hopes of engaging a wider audience than my first book did, because I felt these issues were of vital public interest.

How to write for an audience beyond scholars, though, is a tough question. My mantra was this: “Your reader is smart but not an expert.” In other words, assume your reader can follow arguments but not that she has much prior knowledge. And the way to engage that reader, I decided, was to focus. I picked the issues that seemed most important and shone a fairly tight spotlight on them, making fewer of the side-hops and nods to adjacent issues that we historians do when we’re writing for people who already know the literature. When possible, I tried to present issues through a medium-size set of recurring individuals rather than barraging my reader with many new names per page.

Michael, you write that this is a “condescending” approach to readers, one that “looks down on them from on high, not believing those readers can handle the actual complexities of the stories at hand.” I don’t see it that way. I think it is a reasonable accommodation, designed to ease the entry of a non-initiated reader into a world of important ideas. Frankly, I wish we wrote with more openness to non-experts in our monographs.

Andy Seal wrote a nice reflection on these and related issues as pertaining to my book for this blog last year: https://s-usih.org/2019/05/arrogance-and-empire-what-can-us-intellectual-history-learn-from-us-and-the-world/

To be clear, I’m no fan of the writing style of a lot of historical monographs, or academic writing in general, but I’m not entirely convinced of the “general audience” and “non-initiated reader” arguments either. Frankly, I still hear a condescension in the way you are approaching the matter, and sense it in the writing style of the book too. The choice you made to “present issues through a medium-size set of recurring individuals rather than barraging my reader with many new names per page” produces a kind of great man history, and that may be doing a disservice to your very mission to “ease the entry of a non-initiated reader into a world of important ideas.”

As a followup, I think the bigger issue here—and I agree that it is a challenge—is to rethink the way we categorize “expert” and “non-expert.” I’m just not entirely positive that these categories are accurate. There are so many assumptions built into them—in some ways your approach merely reproduces the very problem you seek to address. Form is content and content form here. The choices made narratively (character driven, medium cast) perhaps are part and parcel of the argument’s problems with the re-assertion of the very concealing of Imperialism that you seek to unmask. That’s what I worry about.

In this sense, Andy’s piece, which I remember reading when he published it, begins to ask the right question, but not quite. The question becomes something more like “popular history”: for whom, and on what terms? That strikes me as the challenge we face. Otherwise one is, in some sense, just feeding the existing beast rather than reshaping what history is, or might be, as a popular project.

To ask the question popular history for whom, on what terms is as much to raise questions about the forms and prose of specialized scholarly writing as its current opposite. It might be about trying to come up with some new categories of what constitutes effective historical writing itself.

This review certainly convinces me that HTH (which I haven’t read) should have paid more careful attention to the concept of non-incorporated territories, to Puerto Rico’s status as a non-incorporated territory (even after being re-labeled a Commonwealth), and, probably, to the frame of the Greater Caribbean.

However, there are other parts of the review that seem somewhat less convincing to me, a reader admittedly ignorant of a fair number of the details that the reviewer discusses. (Caveat that I just read the piece on the screen, which for a long review like this is less satisfactory than printing it out and reading in hard copy.)

For instance, Prof. Macpherson endorses what she characterizes (presumably accurately) as Paul Kramer’s view that historians should, in effect, abandon, or at least move away from, the “binary” of formal and informal empire. For some purposes, I’m sure that makes sense. But the distinction between formal and informal empire is in some respects actually a useful one, provided that it is not taken as a kind of master key that can unlock the whole history of the “U.S. in the world” or anything else — no single conceptual distinction, of course, can do that.

Historians, no matter how steeped they are in the complexities and dynamics of regional history and no matter how committed they are to transcending the nation-state as a “unit of analysis,” need to recognize and acknowledge that there are such things as formally sovereign nation-states and that the formal legal status of sovereign independence does bring certain benefits to a collectivity or polity, no matter how weak or subjugated or marginalized that sovereign state might otherwise be and regardless of whether it plays a subordinate role in the U.S.’s (or any other country’s, for that matter) informal empire. A country such as Djibouti, for example, might be considered in some respects part of the U.S.’s informal empire but its status as a sovereign state means that it’s in a position to negotiate a substantial payment from the U.S. in return for hosting a U.S. military base. If Djibouti were a formal colony or non-incorporated territory of the U.S., like Guam, it couldn’t do that.

The review, if I recall correctly, mentions that only 43 percent of UN member states agreed that Puerto Rico had been decolonized in 1952. I’d say it hadn’t been decolonized: it wasn’t made an independent sovereign country or put on a path to U.S. statehood. Would Puerto Rico be better off as an independent sovereign entity in the U.S. “sphere of influence” or better off as a U.S. state? Prof. Macpherson views its current status as, in effect, that of a colony, but I get no clear sense from the review of which status for Puerto Rico would be preferable. In a way I guess that’s unsurprising, because if you think the formal/informal “binary” is misguided then perhaps you aren’t going to be inclined to address that question explicitly.

Michael Kramer, in his comment above, suggests that in writing for a broad audience Immerwahr might have condescendingly assumed that “general readers” can’t handle historical complexity. While Immerwahr might have hoped to reach a broad audience, a lot of his readers (I don’t know what fraction) are probably going to be students and their professors. A problem with including more complexity, of course, is that tends to require greater length, unless the chronological scope of the book were to be shortened. That’s not to make excuses for Immerwahr, but I think the difficulty of balancing length, accessibility, and complexity shouldn’t be underestimated. Steven Hahn’s A Nation Without Borders, a book I’ve mentioned in other comments here, does well with complexity but it’s so long and in a sense exhausting that I got most of the way through and then didn’t finish and still haven’t been motivated to do so. Well, I’ve gone on long enough.

I agree with Louis that differences along the spectrum of US imperial practices matter a great deal, and that the possession or lack of sovereignty is among the most important of those differences. For example, the Puerto Rican government, for all its faults, is 100% dependent on the CDC for Covid-19 testing, while Belize, with a fraction of the population but a sovereign nation-state, has been able to send hospital staff to Mexico for testing training. Belize can engage in international cooperation and exercise sovereign power in ways that Puerto Rico simply cannot. Puerto Rico is a colony in which only a tiny minority of the people want to become a sovereign republic. Absolutely that fact has been shaped by U.S. and territorial authorities’ surveillance, harassment, and persecution of independentistas, and of the lack of a generous US economic runway to independence including ongoing US citizenship. But it’s also shaped by Puerto Ricans’ perceptions of neighboring sovereign Caribbean states, including the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, and Cuba, which brings us back to the larger dilemmas of the Greater Caribbean in a neoliberal “post”-colonial world.

This issue of sovereignty highlights why it’s so important to distinguish between incorporated and non-incorporated territories. The 30+ incorporated territories have all become states and were never subject to the non-incorporation doctrine. U.S. imperial practices vis-à-vis the incorporated territories were simply different, and the U.S. ongoing status as a “formal” imperial power is because of the five non-incorporated territories. Non-incorporation is enormously consequential and a key feature of U.S. imperialism.

In 2012, Puerto Rico held a referendum asking voters whether they wanted to continue or end their current relation with the United States. 54% voted in favor of ending the current relation, 46% in favor of maintaining the current status. A second question asked voters to indicate their preference for statehood, independence, or becoming a sovereign nation in “free association” with the United States. 61% chose statehood, 33% chose free association, 5% chose full independence. The Puerto Rican non-voting delegate to Congress drafted a statehood for Puerto Rico bill. Congress did not take up the measure in any fashion. In 2017 Puerto Rico held a second referendum on statehood, limiting the question to whether to move forward now. 97% voted yes. Voter turnout was low, which limits what can be said about what the result indicates of Puerto Rican public opinion. The Puerto Rican delegate again introduced a bill that would incorporate Puerto Rico into the union as a state in 2021. Congress once again has not scheduled any hearings or discussions responding to the bill. The Puerto Rican has been considering including the question, “Should Puerto Rico be admitted immediately into the Union as a state?”, on the general election ballot for November 3, 2020. The ballot proposal includes measures to force Congress to respond. Congress has generally never paid attention to Puerto Rican public opinion. In 1914, the elected House of Delegates in Puerto Rico voted unanimously in favor of full independence. Three years later, Congress made all Puerto Ricans US citizens.

Thank you for this, very interesting and most of it I was not aware of. I infer that the recent weight of Puerto Rican public opinion favors becoming a state in the Union, though that 97 percent figure probably is somewhat misleading because, as you say. of the low turnout in that referendum.

Sorry, that period should be a comma, of course.

Louis, Puerto Rican public opinion has been shifting toward statehood, but there has never been a truly clear majority on a referendum. There is still a hefty block that would prefer “enhanced” Commonwealth status with more local autonomy. Every answer to the status question has to balance citizenship, free access to the US metropole, economic benefits, and the status of Spanish as the language of education/business/government and the status of Puerto Rican cultural traditions and practices. Many view independence as too risky economically, especially if the US would not guarantee ongoing (dual) citizenship and visa-free movement. As a non-Puerto Rican I have the luxury of not taking a definitive position, but I also feel that non-Puerto Ricans should not tell Puerto Ricans how to answer the status question. As a dual Canadian-US citizen what I can do is work to elect US leaders who will take a respectful and generous position toward Puerto Rico.

To Anne Macpherson: Thank you for the two comments here. I completely agree with not telling Puerto Ricans how they should answer the status question.