The Book

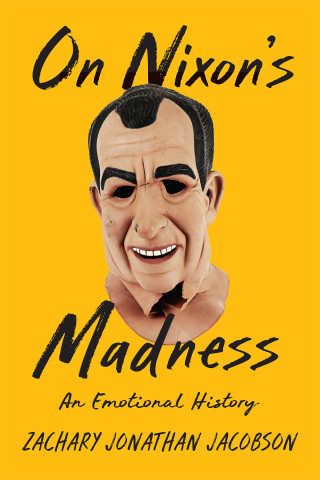

On Nixon’s Madness: An Emotional History

The Author(s)

Zachary Jonathan Jacobson

A couple of weeks ago, during a candid conversation with a dear friend of mine, Zachary J. Jacobson’s book on Nixon’s Madness came up. Politics and art are the main themes we usually talk about. Coming from different countries and cultures (Brazil and the US, for instance), we look for qualified insights on what’s happening in each other’s local contexts. My friend was intrigued by the book’s title. – “Huh, interesting approach”, he said, “I might read it”. – “It’s a psycho-history”, I told him, literally quoting how Jacobson himself describes his own work (p. 4). – “Psycho-history lol” was his immediate response.

At first, I didn’t catch why he thought the definition was so funny. Jacobson sounded quite serious and academic alerting his readers that “it’s a psycho-history, but not in the classic sense of pursuing an analytical diagnosis. Instead, the work examines one of Nixon’s ideas – the madman theory – as an avenue to understanding his subjectivity, perspectives and motivations”.[1] Having finished my reading – actually, during the process of reading – I think I got the reason my friend was laughing out loud. He wasn’t mocking the approach or the field of research. He was, in fact, playfully recognizing that probably no other political character would fit so well in a psycho-history.

This anecdote only goes to show how passionate, sarcastic, critical, or angry a citizen living in the third decade of the 21st century can be about a President whose administration fell apart in 1974 and whose past actions can no longer influence one’s immediate life. Jacobson’s work helps us to understand why and how it happens.

The book isn’t a biography, or even a historical biography. As mentioned, it broadly inscribes itself under the rubric of cultural and intellectual history, and narrowly within the intersections of history and psychology. For that matter, we get 2 quotes from Lucien Febvre in the first 17 pages. It goes without saying that to deal with Richard Nixon and his “madman theory”, Jacobson’s research dialogues intensely with the history of the political.

The author writes beautifully, his prose constantly searching for the sentiment of his subject. Jacobson invests in an “emotional history”. He organizes his presentation like a play: stage setting (introduction), two acts and a closure. The narrative draws its cadence from a skillfully constructed storytelling interrupted by interludes in which the voice tonality changes. Here the author frees the narrative of rigid chronology; we are put in contact with theories, historiography, different characters, different lens through which one can look at and into the theme. These features proved to be effective in bringing Nixon to the forefront of the stage as a performer, “a man of many masks”[2].

Part I is called “On acting” and demonstrates how much effort Nixon put in the construction of both his personal past and his public image. Self-control, careful choice of words, diplomacy, the look to the past through sentimentalism, “[favoring] archetypes (…) rather than the drawn and detailed characterizations of realism”[3]. Part II, “On madness”, focuses on Nixon’s temper, his conspiracy hysteria, his unrelentless drive for revenge. The description of the roles played by the former President are based upon different sources: press publications, biographies, recorded tapes, classified documents made available in the 21st century, and the historiography about Nixon and his epoch that piles up year after year.

Rather than scrutinizing Nixon’s trajectory and the events Jacobson chose to narrate, I want to point out the book’s strategy of analysis. The author rightly avoids the trap of “the real Nixon”. Without neglecting psychological approaches or biographies from writers across the political spectrum (among which is Nixon himself), Jacobson is much more interested in the conditions of possibility of the public construction and political success of a performer who acted as Nixon did. From a historiographical standpoint, the following passage illuminates the issue:

Psychohistorians looked to his childhood to locate the source of his aggrievement. Biographers pointed to an ever-accumulating sense of being wronged over the course of his political career, and then revisionists upended the debate by arguing that it was Nixon’s critics who had invented the notion that bitterness and woe had guided the former president. Cultural historians shifted the debate to note that a conspiratorial mentality had consumed much of Nixon’s generational cohort.[4]

These are some of the questions and the lessons the reader might bring home. Who owns the real Nixon? Is it still worth asking the question? Or is it much more urgent to consider the question of the politician as performer? Having Nixon manipulated his own image so well to convey a public persona while acting “madly” behind the scenes, shouldn’t we interrogate our own role as spectators of this performance? Are we merely spectators in the first place? Were there then and is there today any chance of getting to the real men and women acting in the political arena?

In an interview about the historiography on Nixon, the well-known historian David Greenberg has recently argued that history will tell whether the Watergate scandal will be surpassed by the wrong doings of the Trump Administration.[5] It is almost – if not entirely – impossible not to think of Donald Trump or, say, Jair Bolsonaro (to stick to a local example in the case of this reviewer) when reading about the cultivation of a public and mediatic image which captures the “conspiratorial mentality” that consumes a generation, as cultural historians have pointed out about the 1960’s and 1970’s. These performers play emotionally, they captivate by images and words, they are constantly mediated and validated by the circuits of (mis)information.

However, it is reassuring to know that history is capable of reinventions. Not that type of reinvention that manipulates the past to deny it, but a methodologically audacious reinvention. One that searches for things as evasive or ethereal as sentiments and emotions – aren’t they so real? – with the same passion that it searches for rough facts – are they even there? – in the intersections of the historical, the political, the cultural and the psychological. On Nixon’s Madness is one of these reinventions. It reminds the public that, for performers, much more important than being real is the appearance of being real, of being, like Pompeia, above suspicion. History acts against the grain when it acknowledges the skillfulness of those wearing masks while it opens up the door to the backstage.

[1] Zachary J. Jacobson, On Nixon’s Madness. An Emotional History. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2023), 4.

[2] Jacobson, On Nixon’s Madness, 14.

[3] Jacobson, On Nixon’s Madness, 72.

[4] Jacobson, On Nixon’s Madness, 123.

[5] David Greenberg, “The Best Books on Richard Nixon”, interview by Eve Gerber, Five Books, August, 12, 2022. https://fivebooks.com/best-books/richard-nixon-david-greenberg/

About the Reviewer

Marcos de Brum Lopes is a historian from Brazil and currently works as a researcher at the Benjamin Constant House Museum, Brazilian Institute of Museums, Ministry of Culture. His fields of interest are history, public history, visual culture, history of photography, museums and historical archives. He was a Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence at the Spokane Community College, WA (2015-2016) and worked as a Visiting Professor at the Minas Gerais Federal University, in Brazil (2019-2021).

0