Editor's Note

As part of our #USIH2020 publications, we’re sharing a roundtable on “African-American Intellectuals and Their Critics.” Today’s comment is by the roundtable chair, Bryn Upton (McDaniel College): “Out of the Margins.” Check out our full #USIH2020 conference program and updates here.

Federal Theatre Project, Negro Theatre, Sign Painting department, 1936 (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division. The New York Public Library)

During my high school years, I became interested in American history in part because it all seemed so straightforward. There were events that happened in the past, we learned what they were and what they meant, and it was easy to memorize all of it and spout it back in class or on tests. History was simple. In the textbook, history was told like a story, and every now and then there would be a shadow box on the page that would describe the interesting contributions of women or people of color to that story. At the time, I did not realize that this was a literal manifestation of marginalization, as people who looked like me were given limited space on the side of the page. By the end of high school, I had come to understand marginalization and in college I went looking for more of those shadow box people and their stories.

The work of social historians, to explore the history and agency of all peoples, had not quite made it into the textbooks of my high school but the work was there so that in college I was able to begin to discover the wonderful work of the past decades. At the same time, I became aware of cultural history and it attempts to decode the meanings of cultural practices, and now I thought I could start to see American history in all of his colors, genders, and classes. As intellectual historians turned towards social and cultural histories, we have experienced a broadening of definitions and areas of study.

In these three papers we see fresh contributions to the relative dearth of Black voices in intellectual history, for even as we have witnessed increasing efforts to include Black figures from the past into our syllabi and anthologies, there is still work to be done. Here we have a variety of approaches to understanding the past that seek to give attribution to the influence of Black thinkers and leaders in fields that have not given them full attention.

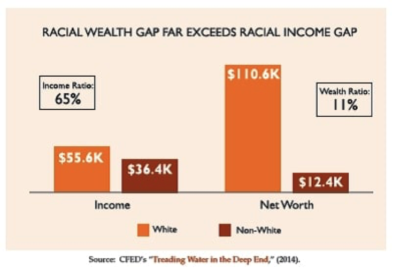

In “Levels of Desire, Levels of Inequality” Ross English examines racial capitalism, specifically, the conflating of the accumulation of wealth with a specific kind of desire and the racialized notion that Black people lack the qualities necessary to acquire wealth. English turns to Booker T. Washington’s assimilative economic message that encouraged Black communities to work within a system that only allowed them certain jobs as a way to garner income. Washington looked to Black labor as the principle mechanism for Black economic advancement. This approach is used to promote the continuation of racial segregation and to place the blame for a lack of wealth accumulation on Black laborers themselves. English calls out Black scholars for perpetuating the mythology of wealth accumulation throughout the 1920s. Drawing from E. Franklin Frazier, English does a good job of exposing the faulty connection between the Black behaviors and the accumulation of wealth. English’s work presses us to ask questions about the role of economic segregation and integration in the accumulation of wealth, but also about the role Black thinkers in promoting one path forward for Black economic development. What role should wealth accumulation play in racial liberation? In a capitalist society, can there be racial progress without economic progress? Does understanding the role of Black intellectuals in perpetuating these beliefs about economic development help us better understand the persistence of the wealth gap?

In “Levels of Desire, Levels of Inequality” Ross English examines racial capitalism, specifically, the conflating of the accumulation of wealth with a specific kind of desire and the racialized notion that Black people lack the qualities necessary to acquire wealth. English turns to Booker T. Washington’s assimilative economic message that encouraged Black communities to work within a system that only allowed them certain jobs as a way to garner income. Washington looked to Black labor as the principle mechanism for Black economic advancement. This approach is used to promote the continuation of racial segregation and to place the blame for a lack of wealth accumulation on Black laborers themselves. English calls out Black scholars for perpetuating the mythology of wealth accumulation throughout the 1920s. Drawing from E. Franklin Frazier, English does a good job of exposing the faulty connection between the Black behaviors and the accumulation of wealth. English’s work presses us to ask questions about the role of economic segregation and integration in the accumulation of wealth, but also about the role Black thinkers in promoting one path forward for Black economic development. What role should wealth accumulation play in racial liberation? In a capitalist society, can there be racial progress without economic progress? Does understanding the role of Black intellectuals in perpetuating these beliefs about economic development help us better understand the persistence of the wealth gap?

Photographic negative from Sing for Your Supper, 1938-1939. The revue featured the first fully racially integrated cast in a Broadway musical. Source: Sing for Your Supper 255 Photographs. [193] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/musftpnegatives.12330251/.

Bandung Conference, 1955

During the Cold War, the battle lines were drawn differently. Rather that anti-racism and democracy on the one side and White supremacy and fascism on the other, the Cold War gave us an America fighting to hold the center having just defeated the radical right and now facing off against the radial left. Somehow, anti-racism gets sacrificed no matter which side of the ideological spectrum we are fighting. At the height of the Cold War most of American foreign policy was mired in the simple bifurcation of east versus west, Soviet-style communism versus American-style capitalism. Crowded out of this worldview, were non-aligned political ideas, thinkers, and nations. In “Martin Luther King, the Non-Aligned World and US Global Hegemony” Carl Pedersen compares the later work of Dr. King, specifically the final chapter of Where Do We Go From Here? (1967) with ideas emerging in the 1960s that constituted a Third Way. King became increasingly influenced by anti-colonialist movements across the global south, traveling to Ghana, Nigeria, India, and the Caribbean during the late 1950s and into the 1960s. Pedersen discusses the Bandung Conference of 1955 and its influence on the Non-Aligned Movement, and while he cannot show a directly link between King and the conference, he asserts that King was aware of the ideals and no doubt agreed with them. We do know that King met with Pan-Africanists and that he saw the conflicts of the Cold War as unnecessary distractions from the work of anti-poverty programs in America. King opposed the war in Vietnam and rising militarism around the world but was hemmed in by accusations of communist sympathy and a need to maintain a good working relationship with the Johnson administration. Still, Pedersen insists, seeing King as merely a proponent of peace oversimplifies his message. It is here that Pedersen is at odds with President Obama’s assertion that King was not addressing “the world as it is” when he accepted his Noble Prize in 1964, but Obama believe he, as president, had to do just that when he made his own Nobel Prize speech. Pedersen is calling for a more accurate portrait of King’s foreign policy ideas than is commonly remembered, and one that would not have allowed King to fully support Obama’s policies in the middle eastern wars. Pederson calls attention to our propensity to simplify King, or use King as a straw man for modern debates, but is Petersen falling into the same trap by reaching for a connection between King’s worldview and Bandung? Is King underestimated on foreign policy because of the outsized role he played in domestic struggles during the civil rights struggles of the 1960s?

In each of these papers the authors seek to enhance our understanding of a specific idea but in doing so allow us to expand the parameters of Black intellectual history. Tracing the modern wealth gap to an ideology that claimed Black people were responsible for the lack of Black wealth and seeing the role that some Black intellectuals played in promoting that idea allows for a more complete picture of Black intellectual discord in the early 20th century. This is an important challenge to many portrayals of Black thought as always being aligned around a single point of view. Illuminating past attempts at promoting anti-racism and Black art as essentially American helps reveal the longstanding rift between those who would promote racial progress and those who support White supremacy. This work helps us better understand the depths of our current struggles for progress. Expanding our understanding of the worldview of one of the most beloved Black intellectuals of the 20th century, who challenged the central tenants of Cold War ideology, encourages us to see the struggle for racial progress as international. This will be critical in the years ahead as the United States begins to reengage with the world after four years of withdrawal from our responsibilities as a world power. The authors of these papers have helped move Black thought from the margins to the center of the page.

0