The Book

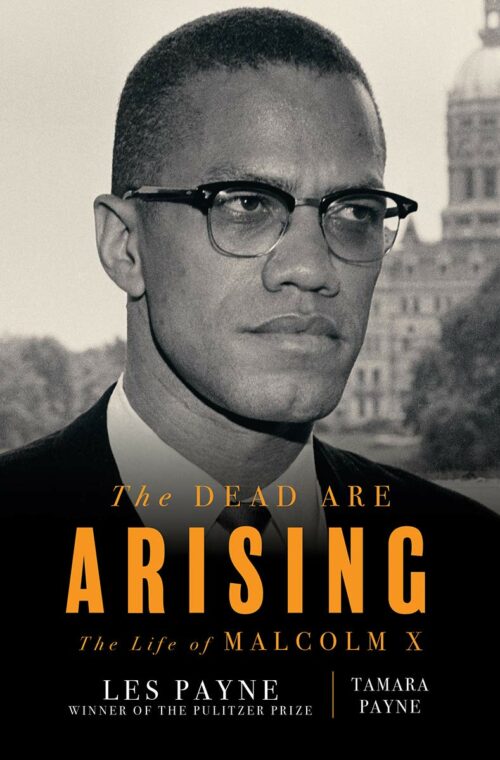

The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X (New York: W.W. Norton, 2020)

The Author(s)

Les Payne and Tamara Payne

“Once you change your philosophy, you change your thought pattern. Once you change your thought pattern you change your attitude. Once you change your attitude it changes your behavior pattern.” These words, from the famous “Ballot or the Bullet” speech by Malcolm X on April 12, 1964, show just how important Malcolm believed developing a stable and usable Black revolutionary nationalist ideology was to his political, social, and intellectual worldview. Thinking of Malcolm as both an activist and an intellectual is essential if one wishes to understand how he was able to galvanize so many Black Americans in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Putting him in an intellectual conversation with other Black intellectuals and activists—such as Marcus Garvey—helps one to understand the ideological contours of the Black struggle for freedom in American history. This is at the center of the new book on Malcolm X’s life, The Dead Are Arising, by Les Payne.

Payne’s biography is the latest attempt to make sense of the short but eventful life of Malcolm X. A journalist who helped found the National Association of Black Journalists, Les Payne spent decades researching and writing his biography of Malcolm X. Passing away in 2018 before being able to finish what became his life’s work, Payne’s daughter Tamara Payne finished the book. The decades of interviews and research Payne did for the book are the foundation of the rich narrative that he produced. In the process, Les Payne made sure to situate Malcolm’s life within the larger history of Black nationalism in American, and world history.

One way this was done was via spending considerable time on the background of Malcolm’s parents, Earl and Louise Little. Malcolm’s own family, in fact, serves as a representation of Black life in America at the turn of the 20th century. Louise, originally from Grenada, comes to represent the growing population of Black Americans in the United States whose origins were in the West Indies. Earl, being from Georgia, represented another tradition—that of the Deep South. “Communal cross-pollination between black immigrants and American-born Negroes,” argued Payne, “gave birth to a heightened sense of group engagement generally—as it did specifically in the marriage of Louise and Earl Little” (77). Much of this is already known by anyone with a passing familiarity with Malcolm X. But Payne goes further, digging deep to showcase how deeply entrenched them both were in the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) of the 1920s, the organization of Black nationalism founded by Marcus Garvey.

The Dead Are Arising works as both a text on the life of Malcolm X and the larger history of Black America. Again, Payne’s deep dive into the parents of Malcolm X also helps to give a sense of how the Great Migration changed Black life in America. If anything, Payne’s biography of Malcolm is as much a story of geography in Black American life as it is a thorough investigation of Black thought in the 20th century. Of course, these two ideas cannot—and should not be—separated.

The complicated legacy of Black nationalism is at the heart of The Dead Are Arising. Intellectual historians have wrestled with the ideology for generations. Books such as Negro Thought in America: 1880-1915 (1963), Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967), or The Golden Age of Black Nationalism: 1850-1925 (1978) played a crucial role in shaping how academics viewed the idea of Black nationalism as historians and lay people alike tried to think through the dynamics of the Black Power Movement. Add to this the recent works of Peniel Joseph, Keisha Blain, Ashley Farmer, Robyn C. Spencer, and many others, and it is easy to surmise that Black nationalism continues to be a critical part of the larger mélange of Black American history. Les Payne’s work benefited from some of the latest turns in Black nationalist scholarship, coming as it does within a larger turn in the field of studying Black history—there is a nuance that is needed to understand what Black nationalist activists and revolutionaries did, believed, and acted upon throughout the 20th century. Certainly, Malcolm X was no different.

This is something to keep in mind as we arrive at a part of the book that has stoked considerable discussion of the legacies of both Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam: his secret 1961 with members of the Ku Klux Klan in Atlanta, Georgia. As Payne points out, meetings between Black nationalists and members of the KKK were nothing new—Marcus Garvey met with the group in 1923. The meeting made perfect sense, at least for one strain of Black nationalist ideology: “…(Elijah) Muhammad drew no distinction between the hooded knights and other whites, branding them all as irredeemable ‘blue-eyed devils.’ If anything, both Garvey and Elijah Muhammad appreciate the ‘honesty’ of the white Knights—and showcased the Klan as representative of all Caucasians” (335). Payne makes clear Malcolm’s deep discomfort with the meeting. This was born partly out of Malcolm’s own experiences with groups such as the Klan as a young boy in the Midwest, but also due to his own growing rift with Muhammad and the rest of the Nation of Islam.

The Dead Are Arising is a valuable book for intellectual historians, as it delves deeper into how Malcolm’s thinking changed during the final years of his life. His internationalist thought becomes a key part of the story of his final two years, estranged as he was from the Nation of Islam and as he struggled to form the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in Harlem. While much of this is likely well known to most historians of the Black experience in America, it is still useful to see it all laid out in minute detail. Where The Dead Are Arising arguably surpasses other biographies of Malcolm, however, is the rich detail unearthed by Les Payne via years of painstaking research and interviews with virtually everyone Malcolm ever known.

How Malcolm thought about the world—and the place of Black people in it—will continue to intrigue intellectual historians for the foreseeable future. It is a shame that Les Payne did not live long enough to read Michael E. Sawyer’s book, Black Minded: The Political Philosophy of Malcolm X, which attempts to deal with Malcolm X as a philosopher of the Black experience in the 20th century. I would argue that the two books are good companions for one another, as Malcolm is the kind of thinker who, over fifty years after his death, escapes simple definition.

About the Reviewer

Robert Greene II is an Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University, as well as blogger and Book Reviews editor for the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians. Dr. Greene has also been published in The Washington Post, The Nation, Jacobin, In These Times, Oxford American, and other publications.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

The deep research on Earl and Louise Little’s stories made me think of the continued relevance of Charles Payne’s arguments about inter-generational political and cultural organizing traditions in Mississippi. Do you think that connection fits with the findings and argument in The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X?