The Book

Reframing 1968: American Politics, Protest and Identity (Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

The Author(s)

Martin Halliwell and Nick Witham, editors.

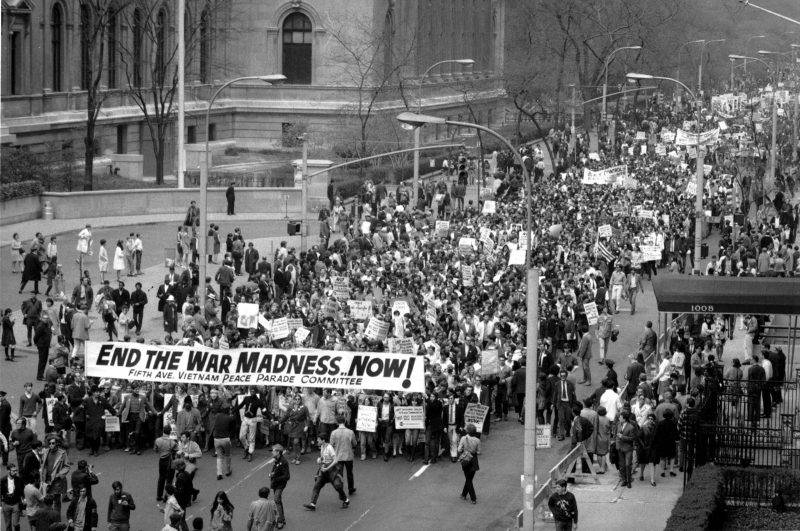

For many, 1968 remains a crucial political year, representing a turning point for U.S. culture and America’s “rendezvous with destiny” (297). In the eyes of both participants in the events of that year and a latter generation of historians, it defines what the long 1960s wrought. However, 1968 was not all Bill Ayers’ “year of wonder and miracle” (96). It is also remembered for less comforting events, such as the violent protests at the Chicago Democratic Convention, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the deaths of 16,889 American soldiers in Vietnam, and the communist Tet Offensive that hastened the de-escalation of an ill-conceived war, the feminist protest of the Miss America pageant, and the commercialization of the counter-culture. Regardless of how one interprets the year—as either a rupture from the past or a time reflecting critical recalibration of slow changes over decades—it will continue to be studied for the loss of national innocence, the questioning of American exceptionalism, and the cultural products such as Paradise Now from the Living Theatre.

Reframing 1968: American Politics, Protest and Identity reconsiders the sweeping changes in both politics and culture in a collection of thirteen essays by scholars in the U.S. and England. The volume focuses on the fracturing of radical politics into more culturally pervasive social movements. The editors, Martin Halliwell, professor of American studies at the University of Leicester, and Nick Witham, lecturer in U.S. political history at University College London, understand the lack of consensus on the significance of 1968. Novelist Paul Auster described 1968 in the New York Times as “the year of years, the year of  craziness, the year of fire, blood, death…the world seemed headed for an apocalyptic breakdown,” only to mourn that for all the agitation, it had not accomplished much of anything, but was ultimately thrown into the dustbin of empty gestures and rhetoric (30). With all this in mind, the essays attempt to explore the historical weight of 1968 and avoid casting an ideologically polarized image. Moving beyond “fetishization” of the events of that year, the collection considers the conflict-fraught emergence of the New Right, the end of the Civil Rights era, multiple conflicts as the New Left fell apart, and how artists and profit seekers capitalized on new cultural values (5).

craziness, the year of fire, blood, death…the world seemed headed for an apocalyptic breakdown,” only to mourn that for all the agitation, it had not accomplished much of anything, but was ultimately thrown into the dustbin of empty gestures and rhetoric (30). With all this in mind, the essays attempt to explore the historical weight of 1968 and avoid casting an ideologically polarized image. Moving beyond “fetishization” of the events of that year, the collection considers the conflict-fraught emergence of the New Right, the end of the Civil Rights era, multiple conflicts as the New Left fell apart, and how artists and profit seekers capitalized on new cultural values (5).

The editors offer four themes for the volume: Memories of protest; the multiple forms of protests and their ambiguous effectiveness; ideological splits within the New Left; and American connections to the international turbulence of the time. They frame the New Left as marked by tensions between its adopted universalizing humanist values of the post-World War II period and an emerging identity politics at the decade’s end. How the New Left engendered multiple identity movements, some quite independent from it, and established a new sensibility for social and political protest holds the volume together.

Memoirs, biographies, and essays of participants have nurtured much of the memory and scholarship of 1968. Witham’s essay “Life Writing, Protest and the Idea of 1968” considers the memoirs of Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, written in the 1970s, which portray the period as one of generational conflict and a rejection of their parents’ expectations of adulthood. Tom Hayden and Todd Gitlin, writing in the 1980s as “survivors of a generational diaspora,” remembered 1968 as the year the New Left lost its way (88). They reconsidered the movement’s failures and meager successes. Susan Brownmiller, writing in 1999, viewed 1968 as halcyon days for radical feminism and a starting year for a critique of patriarchy. These personal accounts are the first drafts of history by which historians of the last two decades began to excavate for “the truth” of that pivotal year.

“The New Left: The American Impress,” an essay by Doug Rossinow, addresses the movement as a vision for both personal and societal transformation within a context of globalized protest. The American New Left shaped the international scene as people began to recognize the U.S. as an imperial power thanks to its actions in Vietnam. Rossinow argues that protests against the system, leaderless and structureless, became “features and not bugs” of subsequent social movements (16). He sees 1968 as the splitting-off point for other radical movements after the New Left attempted to corral radicalized African Americans and women within its universalist (read “straight white male”) camp. To claim their own distinct political voice, many gays, ethnic minorities, and women rejected the New Left. Already weakened by 1968, the movement had three possible trajectories: One, escalate the confrontation with the system followed by action from small groups of revolutionaries like the Weather Underground. Two, build alternative communities, based on what Rossinow describes as “post-scarcity white liberalism,” within existing society. Three, reconcile itself to reform within the standing political system by “colonizing” major institutions, becoming what Régis Debray described as the legacy of 1968 in France, “the cradle of a new bourgeois society” (23). What remained of that generation’s substance were the diffused values of direct action, political resistance, and the search for authenticity.

Daniel Matlin takes a look at American cities from San Francisco to New York as both the site and the focus of protest, representing both oppression and, in the words of Charles Baudelaire, unlimited utopian possibilities of “universal communion” (109). Matlin’s essay, “On Fire: The City and American Protest in 1968,” explores the period’s romance with cities as places of “authenticity and variety,” paving the way for the gentrification of later decades as developers capitalized on urban enchantment (125).

The political upheaval was not all about the New Left and street protest. Elizabeth Tandy Shermer’s essay “1968 and the Fractured Right” recounts the inner tension within the movement between the Goldwater conservatives who had depended on local elites’ effort and popular conservative revolt reflected in the presidential campaign of George Wallace. Historiography continues to illuminates the nature of the deep division within the ranks. The right’s architects were committed to what Shermer describes as “efficient, corruption-free, free-enterprise governance,” a feature of the post-war generation while a new constituency of suburbanite citizens’ demanded property tax abatements, personal prosperity, and the protection of racial and religious values (43).

The politics of 1968 also resonated with broader change, and Sharon Monteith’s essay “1968: A Pivotal Moment in Cinema” illustrates how cultural change was seen in the films of that year. More than half of the U.S. population was under twenty-five, and filmmakers began to cater to a restless youth culture. Political dissent and the counter-culture became commercialized. The end of the Motion Picture Production Code, the industry’s moral guidebook, and the implementation of a rating system allowed freer depiction of sexual liberation and lived dissent on the screen. That year’s films in production included The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, Easy Rider, and Alice’s Restaurant, which all helped spread counter-culture ideas.

Other essays address Vietnam as the entryway to a state of permanent war; performance art that mixed low and high culture and reminding me of George Cotkin’s excellent study Feast of Excess: A Cultural History of a New Sensibility (2015); students’ demands for their educational curriculum’s relevance to  social problems via the inclusion of race, class, and gender issues; the confluence of the Civil Rights movement and the broader Poor People’s Campaign and the emergent gay liberation and many other topics. The afterlives of 1968 mentioned include later movements that embraced the values forged in the 1960s, such as the confrontational style of 1990s Queer Nation, the protest of the 1999 WTO Conference in Seattle and the Occupy Wall Street movement that began in 2011, and recently Black Lives Matter, which depended on grassroots and underground communications channels for mass mobilization. All demonstrate the mark left by 1968.

social problems via the inclusion of race, class, and gender issues; the confluence of the Civil Rights movement and the broader Poor People’s Campaign and the emergent gay liberation and many other topics. The afterlives of 1968 mentioned include later movements that embraced the values forged in the 1960s, such as the confrontational style of 1990s Queer Nation, the protest of the 1999 WTO Conference in Seattle and the Occupy Wall Street movement that began in 2011, and recently Black Lives Matter, which depended on grassroots and underground communications channels for mass mobilization. All demonstrate the mark left by 1968.

This is a superb collection with solid scholarship and lively writing appealing to specialist and non-specialist alike. However, with the exception of Rossinow’s essay, it fails to deliver on its promise of an international assessment that decenters the nation-state. I would have liked to read more on the shaping of the global New Left by American film and music, political protest, and dissemination of counter-culture values. That might have been too much to promise or expect in 320 pages. It remains an excellent collection for starting a conversation on the legacy of 1968.

About the Reviewer

Lilian Calles Barger is an intellectual, cultural, and gender historian. Her book, titled The World Come of Age: An Intellectual History of Liberation Theology, is forthcoming in the summer of 2018 from Oxford University Press. She is currently researching the history of feminist thought and the gender revolution.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Lillian,

I’m always happy when a review doesn’t turn me away from a book I had planned to read (that it may turn me away is of course not necessarily the fault of the reviewer, it’s just that it’s nice to have one’s initial impressions confirmed!).

While you would have preferred “more on the shaping of the global New Left by American film and music, political protest, and dissemination of counter-culture values,” I happen to be curious about the direction of cause and effect proceeding in the other direction: how did the global “New Left” (for the characterization of which I refer the reader to Katsiaficas’ 1987 book, The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968) shape not only “our” New Left’s political thought and praxis, but its counter-cultural orientation and the wider culture (including the ‘culture industry’) as well (e.g., film and music)? Perhaps the answers to that question are more interesting if not surprising.

Thank you for your comment. You are quite correct as my comment attempted to address what appeared in the introduction as an offer of showing how the U.S. shaped globalized movements. It’s not developed very much. Yes, the direction of the New Left flows in and out of the U.S. and other parts of the world. The post-WWII anti-colonial movements offered a ready model not for the U.S. New Left itself but for the identity movements that either broke away or refuse to be captured by it; Black Power being one of them in which the AA community is seen as an internal colony in need of liberation. But I am sure you are well aware of all that. You might want to offer a review or comments of the Katsiaficas’ 1987 book for S-USIH readers.