Editor's Note

“‘Revolution’ is a key word among many of the wisdom-seekers I’m currently writing about.”—Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen

Need a little inspiration right about now? Here at the blog, we’re visiting with past USIH prize winners to hear what they’re working on, and to see how their scholarship connects to our #USIH2020 conference theme of “Revolution & Reform

Need a little inspiration right about now? Here at the blog, we’re visiting with past USIH prize winners to hear what they’re working on, and to see how their scholarship connects to our #USIH2020 conference theme of “Revolution & Reform

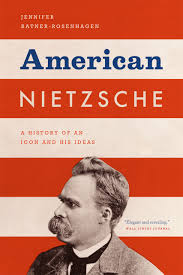

.” First up, we chatted with Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, Merle Curti and Vilas-Borghesi Distinguished Achievement Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who won the 2013 S-USIH Book Prize. Check out her American Nietzsche: A History of an Icon and His Ideas (University of Chicago Press). Psst, #USIH friends! There’s still time to enter YOUR book for our annual prize. Entries are due 15 April 2020

and you can find all the submission details here.

What are you working on now?

Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen: I’m currently writing a history of ideas about—and the struggles to attain—wisdom in the 20th-century United States. My book examines how a variety of Americans over the course of the century understood wisdom, why they craved it, and how they sought to use it to remake themselves and American society.

In our current volatile, fractious, authoritarian, and hyper-ideological moment, with the world lurching toward irreparable climate catastrophe, the word “wisdom” may seem a bit jarring, escapist, and silly. It carries traces of something antiquated, sentimental, or simply impossible to articulate and even harder to achieve. However, my research shows that for generations of serious-minded American intellectuals wisdom, properly understood and utilized, was neither quietist nor romantic. Nor did they believe it to be outsized by the most pressing social, political, and existential issues of their day. Quite the contrary, they believed—and give us reasons to share their perspective—that the absence of wisdom was what caused those seemingly intractable problems and that applying wisdom to the ills of American life was the only way to fix them.

Within our field of intellectual history, what topics or approaches are you excited about?

Within our field of intellectual history, what topics or approaches are you excited about?

Ratner-Rosenhagen: All of them! I’m a big enthusiast of eclecticism in the field of intellectual history, and my reading and undergraduate and graduate instruction reflects that. I’m as likely to read and assign conceptual history, disciplinary history, or an intellectual biography as I am to work with an example of what Sarah Igo has called “free-range intellectual history.” Given that my current work on the history of wisdom shades into religious history and cultural history (literature, the arts), I’m also keeping my eyes out for new scholarship that works between these registers.

This year, our annual meeting theme is “Revolution and Reform.” Can you reflect on how those ideas connect to your scholarship?

Ratner-Rosenhagen:

When working on Ideas that Made America: A Brief History (Oxford University Press, 2019), I tried to examine how revolutions take place in historical actors’ hearts and minds, if not also in their political and economic worlds. Interestingly, “revolution” is a key word among many of the wisdom-seekers I’m currently writing about. The challenge for me is to discern when they’re simply using it rhetorically and romantically, and when they really do have concrete paths to structural change.

0