Yesterday, my family went to a screening of They Shall Not Grow Old, Peter Jackson’s new World War I documentary, which apparently set records for a cinematic “event” (i.e. a special one- or two-day theatrical engagement).[1] Before the film, this fundraising PSA by the United States World War One Centennial Commission for the forthcoming National World War I Memorial in Washington, D.C., played:

I was fascinated by this ad and what it says about World War I memory in this country.

This year marked the centennial of the conclusion of the First World War, an anniversary that passed in this country with relatively little notice, as had 2014’s centennial of the start of the War and 2017’s centennial of American entry into it.

The pitch for the new Memorial is, in effect, built on this absence of memory:

“Today, in our nation’s capital, every major American war fought in defense of freedom is honored with a memorial, save World War I.”

The National World War I Museum and Memorial, Kansas City, Missouri

This claim is, narrowly, true. But, in fact, the nation has major, national memorials to the Great War. Since 1926, Kansas City, Missouri, has been home to the National World War I Museum and Memorial, which features a 217 foot-tall tower. And the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

in Arlington National Cemetery began life as a memorial to a World War I serviceman, though the remains of unknown soldiers from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam were later added.

Nevertheless, it has become something of a cliché that World War I is a forgotten war in this country. That reflects, in part, the relative shortness of American involvement in the conflict. Though (as the PSA for the new memorial notes) more Americans died in the Great War than in Korea and Vietnam combined, the War was much more devastating to the European countries involved in it.

But there’s a larger reason for American forgetfulness of World War I that is, I think, not often enough noted in contemporary, popular accounts of American World War I memory

. World War I was a deeply bitter experience for many Americans. Wartime patriotism was harsh and divisive, with German-Americans in particular victims of their neighbors’ wrath. World War I was the first time the federal government engaged in modern propaganda. It also marked a low point in protections for dissent in America…and things got arguably worse during the First Red Scare that immediately followed the War. African American soldiers, who served with distinction in the war, frequently met racial violence when they returned to the country. And the promises that the War would make the world “safe for democracy” quickly proved utterly false. The often bloodless accounts of the failure of the Treaty of Versailles in the Senate and America’s retreat from the world in the 1920s fails to capture the anger that so many in this country felt about the war’s many broken promises, anger that boiled over when tens of thousands of veterans marched on Washington, D.C. in May 1932, demanding bonus payments that they had been promised.

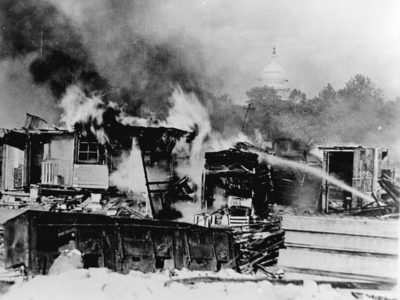

The Eviction of the Bonus Marchers

Police and the Army eventually drove out the Bonus Marchers, an event that contributed to the general sense that the country was falling apart under President Hoover’s failed leadership. A year later, in large measure in response to the Bonus marchers, the Hollywood musical Gold Diggers of 1933 would conclude with a sequence urging the country to remember the “forgotten man” who fought World War I.

Later in the decade, when the Roosevelt Administration faced the task of convincing Americans to take part in another World War (following years of World War I-influenced neutrality toward European conflict), many of the choices reflected a concerted effort not to make the conflict resemble the First World War. American World War II propaganda celebrated German Americans and emphasized that we were fighting Nazism, not the German people. And the countries fighting against the Axis were designated the “United Nations,” in part because the word “allies” had too much World War I resonance.

Now, three quarters of a century later, the United States World War One Centennial Commission, in that PSA for the new memorial, describes the fight with an incredibly generic bromide: “Liberty must always be defended, strengthened, and cherished.”

We usually think of memorials as recording and marking memory. But sometimes the precondition for a memorial is a whole lot of forgetting. Far from overcoming the American forgetfulness about World War I, that forgetfulness is a kind of necessary precondition for the new, celebratory memorial. It’s taken one hundred years for the memory of the actual American experience of the Great War to fade enough for a blandly heroic substitute to be constructed in its stead.

Notes

[1] The verdict: it was a powerful use of period World War I footage and oral histories that provided a real sense of the experience of British infantry soldiers on the Western front but neither attempted, nor offered, any real interpretation of the larger causes or effects of the war. Jackson’s digital enhancement of period film generally worked, though the enhanced faces of the soldier often fell into a kind of uncanny valley. You can get a little taste of the effect here.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

What an excellent point you make regarding the long memories of people angered, disappointed, or (literally or figuratively) alienated by the war. And that sharpness of memory really isn’t so strange, after all, even if it has been a hundred years. Every November I am impressed by the genuine solemnity and passion of English football clubs’ Armistice Day tributes, and just this year an Irish player’s refusal to wear the poppy created a major controversy. The Great War is still so close to the surface of public emotions there–and perhaps here as well, in ways we don’t always recognize, as you suggest.

I share your response to Armistice Day in England. My sense is that a lot of European countries have maintained a kind of mournful memory culture around World War I…and that it is fairly unusual for countries to develop such a culture around the memory of a war that they won. The closest thing I can think of in this country is the “brother-against-brother” memory of the Civil War in the post-Reconstruction North, though that strand of memory was obviously quite pernicious. Sometimes it is better to remember a victory as a victory.

It’s not surprising, I think, that the memory of WW 1 esp. in Britain, France (and perhaps other countries on the winning side too, e.g. what was then, and now is again, Serbia) has a mournful tinge. The war killed or wounded close to an entire generation of young men in Britain and France, and in a war that, in a hypothetical but not too far-fetched alternate scenario, could probably have been avoided (and hence does not carry the stamp of historical “necessity” that World War II does).

Moreover, in Britain (and probably France too, though I’m less sure about that) the casualties were distributed across the whole of the socioeconomic spectrum, with men from the upper classes dying in disproportionate numbers, as the officer ranks that they populated suffered extremely high casualties. So the war had a broad impact, directly affecting the elites as well as the working class (as a small library of memoirs, mostly penned by the educated members of the upper class, shows).

For the Irish player in question, James McClean, the non wearing of the poppy controversy is an annual “event”. Interestingly this past November a Serb player with Manchester United,Nemanja Matic, also did not wear it. While a much more decorated player with arguably the most famous football club Matic apparently was not subject to the same level of abuse as McClean.

https://inews.co.uk/sport/football/premier-league/nemanja-matic-poppy-row-james-mcclean-manchester-united-fc/

Two thoughts:

1. Isn’t the Korean War also, very often, referred to as “the forgotten war”?

2. Isn’t this drive premised on the relatively new fetish, over the past 30 or so years, of power brokers to make DC a central, dynamic place? Isn’t the drive for a WWI memorial there a witness to DC’s new prominence as a metropolitan area in the US landscape? (I say this notwithstanding the original dreams of its benefactors, and primary planner/promoter Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L’Enfant, to make it a “Federal City.”) – TL

The reference to Wash D.C.’s “new prominence” as a metropolitan area and/or tourist destination has a somewhat odd ring, in view of both the 20th-cent. (e.g., first lines of the subway date from the early/mid ’70s) and earlier history of the city. Anyway, it’s less “power brokers” in the sense of national politicians and more local business owners and to some extent large corporations (e.g., the bigger hotels etc.) that benefit from a robust tourist trade — though I think it’s doubtful that a WW 1 memorial, in a city already crowded with memorials, will have much impact on tourism one way or another.

While the city and its environs have arguably long been “dynamic” under certain definitions of that word, it is true that in the last several decades the cultural (as opposed to, say, strictly political or commercial etc.) aspects of the metropolitan area have developed substantially. In theory at least, everyone benefits from that, visitors and local residents alike (though as one of the latter, albeit one who lives in the environs rather than the city proper, I have to confess that I take only intermittent advantage of the area’s cultural life/offerings).

Two excellent thoughts!

1. Yes. I almost mentioned Korea in just this regard in this post. To me the obvious question is: what larger cultural work is the trope of the “forgotten war” doing in our political culture such that it becomes a mantle worth claiming? Of course, once you start talking about a “forgotten war,” it’s no longer really forgotten. Both Korea and World War I, for all their “forgottenness” play much larger roles in 21st-century American political culture than, e.g., 1812, the Mexican-American War, or the Spanish-American War, let alone the Philippine-American War.

2. I hadn’t thought about recent memorial practice in DC as a reflection of the changing ways in which federal lawmakers see the city. In a narrower sense, I think the World War I memorial is an example of the way in which memorialization practices can become about memorialization itself. Since its founding, DC has been a major site for memorials to American military prowess. But until recently, there have not been single memorials to major conflicts. There are many DC memorials related to the American Revolution and the Civil War. There is no National American Revolutionary War Memorial or National Civil War Memorial. Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial changed all that. “There’s a national memorial to the Vietnam War, why isn’t there a memorial to…” begat the Korean War Veterans Memorial (1995) and the National World War II Memorial (2004). Now the argument has become “in our nation’s capital, every major American war fought in defense of freedom is honored with a memorial, save World War I.” Of course, what counts as a “major American war fought in defense of freedom”? Surely by that logic we need a National Civil War Memorial! My guess is that only the continuing power of neo-Confederate memory culture has kept one from happening.