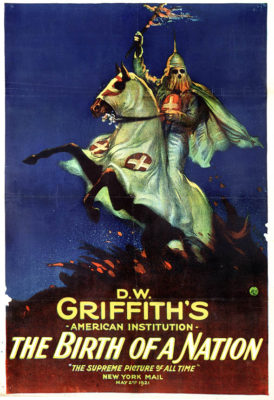

Movie poster advertises ‘The Birth of a Nation’ directed by D.W. Griffith, 1915.

Although I have screened and taught David Wark (D.W.) Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation many times in past courses, it never felt more relevant than when I did so this past week.

That is my post-screening assessment because, right up until class started, I was unsure—debating with myself whether or not to do it. My chief concern was sacrificing time potentially better spent covering textbook material. We have 2.5 hours for class, but the movie is 3.25 hours long. How could I artfully set up the screening and fit it into our time frame? I found a solution to that problem, but I do not yet have a feel for my students’ reception. Even so, I think I used our time fruitfully.

Apart from logistics, from an instructional point of view, the film’s racism, pretensions to history, and ability to showcase the era’s technology, as a “blockbuster” for its times, make it an intriguing vehicle for challenging students. It was a chance to teach with another kind of primary document (Birth was released in 1915). Philosophically, moreover, the objective seemed necessary, even crucial.

I start with the assumption that white supremacy still exists, as an on-the-ground fact and an ideal for some. I also hold that both colorblindness and purported racial innocence perpetuate age-old problems with structural racism. These commitments necessitated, for me, a dramatic visualization of white supremacy.

Backing up a little, my course is Post-Civil War U.S. History. The unit? The 1920s. Having decided on a plan, I executed by starting our session with a short discussion of American Yawp chapter 22, titled “The New Era.” To reach The Birth of a Nation, I needed to steer our discussion, as naturally as possible, to the section on the Ku Klux Klan.

A few students began by conveying their interest in the section on “The New Woman.” The liberating spirit of “The Flapper” seems to perennially capture the imagination, especially of my white female students. The Flapper’s bobbed hair, self-conscious clothing styles, cigarettes, sense of independence, and sexual expression speak to the desires of college-aged students raised, perhaps, in conventional homes. After that the discussion moved to 1920s consumerism. There is a sense, here, that students feel that American culture is moving to something recognizable. Advertising, credit, and shopping were objects of reflection. Next my students brought up The Klan. We spoke of that infamous voluntary organization (They’re not all great, Mr. Alexis de Tocqueville!) being populated by white, middle-class Americans. Courtesy of a prompt from me, directing them to the textbook, we discussed how and why The Klan became a popular culture phenomenon.

The Birth of a Nation receives only brief mention. Here’s the text: “Two events in 1915 are widely credited with inspiring the rebirth of the Klan: the lynching of Leo Frank and the release of The Birth of a Nation, a popular and groundbreaking film that valorized the Reconstruction Era Klan as a protector of feminine virtue and white racial purity.”

By this point we were fifteen minutes into our session, and I needed to start our screening soon (even though I was cutting 65 minutes from its 195 total). I asked, however, if everyone understood the term “valorization” (there were questions) before revealing that we would screen large parts of the film, and explaining why I believed a screening would be advantageous. First on the list was opportunity. When in their lives would they ever take the time to watch one of the most famous silent films of all time? There seemed to be some assent that our class seemed as good a time as any. Because the film is long, and because I would need to keep it going during their customary break, I wanted some consent before proceeding with my plan. To be clear: the consent was about clock and break logistics, not content. On the last, I prefaced the film by saying that if you didn’t find it offensive, in parts, then you weren’t really paying attention. I warned them to expect over-the-top racist caricatures of African Americans.

Returning to my philosophical justification for screening the film, I felt that, in 2018, an explicit engagement with white supremacy in popular culture was an imperative. They had no doubt heard the term ‘white supremacy’, but it seemed appropriate to diver deeper. Although we had discussed eugenics a few weeks before, it also felt that a concrete instantiation was in order. And nothing creates an imprint like visuals.

During the screening I hammered away at the oozing of white supremacy—in each and every title card, historical facsimile, iris effect, parallel action, panning, color tinting, fade out, cross cut, and close up. Griffith utilizes these technical innovations to tell a story that underplays the horrors of slavery, overplays the excesses of radical Reconstruction, and adds the patina of an anti-war message.

Not content to play up the virtues of whiteness, especially of white womanhood, Griffith also weaves a visual narrative of the barbarism and vices of blackness, particularly in black males. I underscored, to my students, the scenes where freed slaves (the disloyal souls, in his terms) were portrayed as uncouth, simple, ignorant, drunken, unclean, and unworthy. I made sure the students understood that Griffith saw race-mixing, intermarriage, and miscegenation as products of moral vice and signs of the decline of civilization. Indeed, those sins are the greatest in the eyes of Griffith and his muse, Thomas Dixon.

I let my students watch the entire slow-played sequence where Gus chases Flora Cameron to her suicide. I reminded them that Gus, since he’s interacting with white actors, had to be a white actor in black face. In the story, Gus had already been revealed as an evil character when he killed a “loyal soul” (i.e., freed slave who remained a servant to the Southern white elite). The chase for Flora ensued because Gus was in a passion for the forbidden fruit of white womanhood. Griffith wants the viewer to know that black men are unable to control themselves when opportunities arise for sexual intercourse with white women. In context of a story about the failures of Reconstruction, Griffith stirred sexuality into an already unstable potion of post-Civil War passions regarding race and power.

A parallel story, in the same section of the film, deals with the rapacious desires of Silas Lynch, a mulatto protégé of Senator Austin Stoneman (a fictional portrayal of Thaddeus Stevens). Lynch’s illicit desires are focused on Elsie Stoneman, daughter of Senator Stoneman. Both Lynch and Gus receive their comeuppance (in the eyes of whites, anyway) at the hands of the Klan, led by Ben Cameron—the eldest scion of the film’s Southern family. Through was Griffith portrays as necessary violence, the Klan restores the rightful racial order, wresting power from anarchist freed slaves and carpetbaggers.

If the racism of the film isn’t offensive enough for modern audiences, its revisionist history should be. The core message of the film, gleaned by Griffith from Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman, is that Reconstruction was an unjust act—a crime against the Southern states and the region’s people, whether black or white. Buttressed by Griffith-branded title cards containing citations of Woodrow Wilson and others, as well as by well-constructed and seemingly trustworthy interludes with historical reenactments, audiences are lulled into a feeling that the film conveys a great deal of historical fact. The words and images give comfort and solidity. The crescendo of Griffith’s historical thinking is that the rise of the Ku Klux Klan was natural, necessary conservation of civilization. The Klan’s revanchism, in Birth of a Nation, was a restoration—of a certain order for a certain race.

Much is, of course, obscured in this. The “moonlight and magnolias” portrayal of slave history in the film’s first half, along with on-screen horrors of war and sympathy for Lincoln, set up the viewer with a sensibility of historical legitimacy. The audience is shielded from complexity. Griffith’s selections rest on his historical assumptions, ignoring facts from other primary resources. It should be clear to today’s viewers that his perverse history exists is founded of white supremacy and post-Reconstruction revisionism. But that “should be” is thing I could not take for granted in 2018.

In one of many centennial reflections published in 2015, film historian and critic Ed Rampell called The Birth of a Nation “the most reprehensibly racism film in Hollywood history.” In his Washington Post article Rampell argued that Griffith, the son of a former Confederate colonel, “amped up the racism” and hyped the “threat of black [political] power.” The film, Rampell continues, surpassed other racist films such as “Judge Priest” (1934) and “Gone with the Wind” (1939). He ranks it with “Triumph of the Will” (1935) and “Jud Süss” (1940) as one of “the most despicable propaganda pictures of all time.” Writing in TIME magazine that same year, Richard Corliss was less strident. He argued that Birth was “nearly as antiwar as it is antiblack.” I disagree, as that buys the antiwar patina Griffith supplies at the beginning and end of the film—obscuring everything that occurs in the second half.

As noted, this revisionist history was put to good use by Klan recruiters. And that usage continued for years and decades beyond the film’s original period of reception. Dick Lehr relayed, in 2015 for NPR’s Code Switch, that David Duke screened and glossed the film as late as the 1970s. Lehr reflected: “[Duke’s] idea of a [Klan recruitment] meeting was to show this film, in which he stood there narrating it and adding his own very racist spin on events. And that’s when it hit me: the real propaganda value for the Klan, not only way back when but here it was, like, six, seven decades later.” As Faulkner famously warned us, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

In the same article, Todd Boyd, Professor in USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, noted that he rarely brings up the film in his classes. And he never screens it. Even though he calls Birth “the foundation of modern cinema” and important, historically, in terms of technological prowess,” he chooses not to make it formal part of the curriculum. Boyd, however, does not oppose other educators’ choices, believing that students should be “exposed to all kinds of information, including uncomfortable ideas.” The way Birth is taught “is more important than the fact that it’s taught,” he adds. Ideally an instructor should “talk about it as representative of racism and white supremacy” in American history.

Returning to 2018, in my classroom, that was the goal. Since the instructional effort is still in motion (readings were assigned, with a study guide, after our screening), I cannot yet draw any conclusions about my success. But the intention was there, and as of today I am pleased with my effort.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Hi Tim,

I was listening to an NPR program yesterday and a person was being interviewed who had witnessed or was reporting on a white supremacy demonstration. One of the snippets I garnered, between getting in and out of the car doing errands, was the distinction some younger participants made about older ones (“Boomers”) who were wearing Klan hoods and Nazi paraphernalia calling it “embarrassing and cringe worthy”. The distinction was evident of a sensibility about how one might appear, as well as a generational divide. Now both groups are still attending some sort of celebration of “whiteness” event and all that that implies but I’m wondering how teaching/showing “Birth of a Nation” could fit in here. I could hear (in my minds ear) younger people saying, “Well that’s not me, I’m not like that I’m just defending the rights of white people”. In other words, how do you make BON relevant without being heavy handed or should you? It appears to me that these younger people don’t see the genealogy of whiteness as a form of bigotry.

Thanks for this comment, Paul. I saw it yesterday, but had a long commute and busy evening at home.

I agree that aesthetics can obfuscate relevant unethical behavior, historically and in the present. And of course questions around aesthetics are separate from questions of undemocratic, uninclusive, and racist behaviors.

My hope, in teaching BOAN, is that we at least see that white supremacy operates, politically and practically, in similar ways across time—even while context matters. I believe my students are smart enough to think about white supremacy apart from the trappings of appearance, and that white supremacy operates apart from appearance.

I mean, if people with shaved heads who wear cargo shorts/khakis, and/or polos, are white supremacists, I guess I occasionally qualify. 🙂 But teaching white supremacy in a history course means that context matters. If I wear those things *and* drive a Dodge Charger into a crowd of antiracist protestors during a white supremacist rally, I might be a white supremacist. In the 1860s, were I to wear a white robe with St. George’s crosses, a pointed hood, and ride a horse, but refrain from assaulting people of color and stand up to undemocratic, racist behaviors, then I’m an aesthetically confused anti-racist. In sum, and as usual in my history courses, we’re always thinking about context and what rises above, as well as past-present differences and connections.

All that said, and apart from the study guide I sent after screening the film, we will have a follow-up discussion in class to tease out some of these points about tensions, context, justice, democracy, etc.

Best,

Tim