Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts on the common readings in Stanford’s 1980s “Western Culture” course. You can see all posts in the series here: Readings in Western Culture.

Per the Kindle app on my phone, I am 64% of the way through Voltaire’sCandide. No spoilers!

I’m serious.

Candide was on the Stanford “Western Culture” reading list thirty-odd years ago, but I’ve never read it before. That’s not because I didn’t do the assigned readings; I always did, with one notable exception that I’ll get to in due time in this series. It’s simply because many of the eight Western Culture tracks, including mine, were already teaching modified versions of the core reading list well before it was officially retired in favor of the common reading list. (There was much overlap between the old “core list” and the new “common list,” a fact lost in many a hyperventilating op ed column by “cultural conservatives.”)

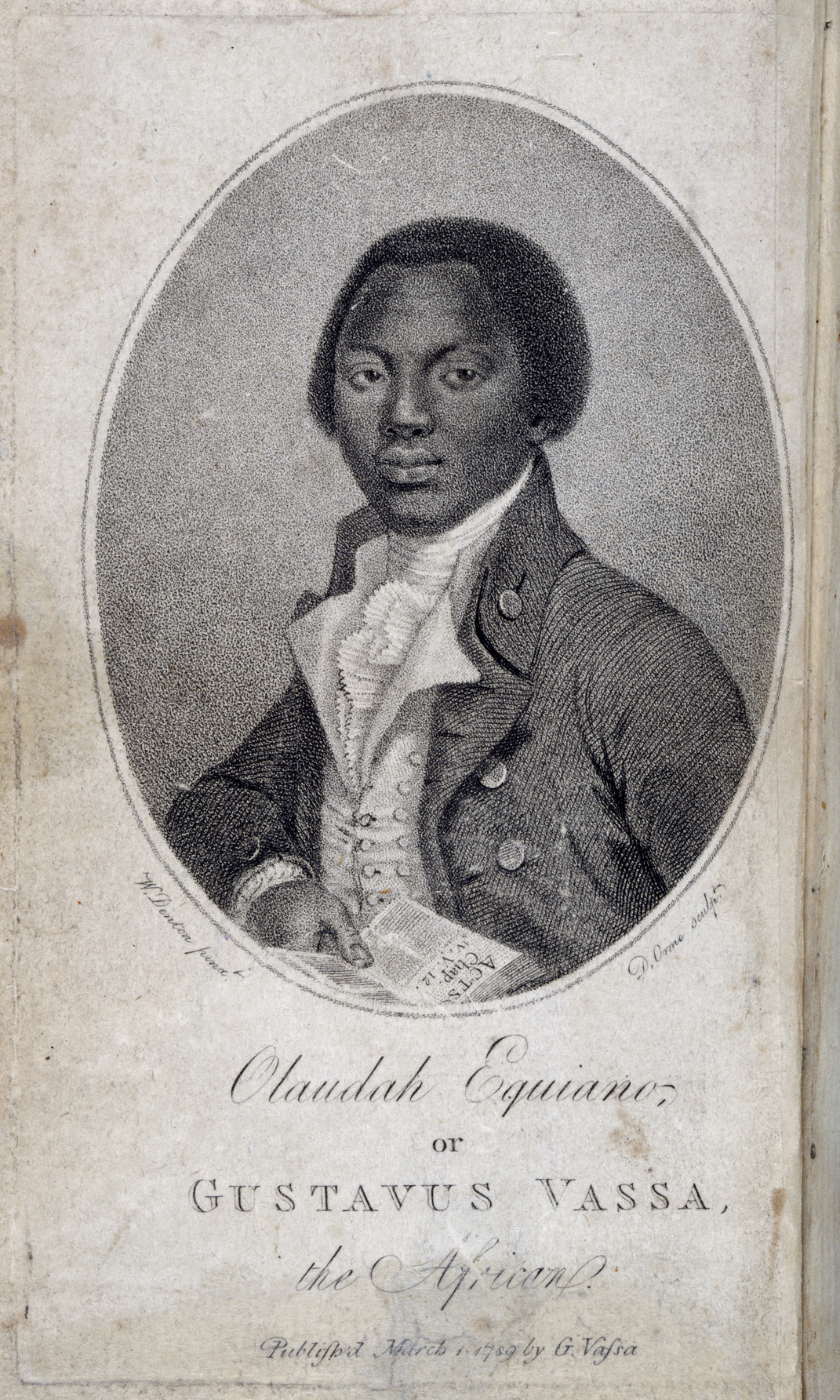

What did we read instead of Voltaire? We read Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography. This was not available in paperback – or, at least, it was not sold as such in the Stanford bookstore (perhaps because it was a substitution for a required text?). Instead, the narrative was included in a large packet of photocopied materials we had to purchase from the Kinko’s in downtown Palo Alto.

Equiano’s life story proved just as much a text of the Enlightenment as Voltaire’s Candide, though Equiano’s is markedly less acerbic, an astonishing fact given his experiences. Equiano’s text diverges from Enlightenment thought in giving the lie to the notion of some innate intellectual or moral inferiority of Africans to Europeans, or of Black men to white men. Chapter 11 of Candide, in which the “Old Woman” relates her history, conveys standard Enlightenment ideas of racial hierarchy. “The northern nations have not that heat in their blood, nor that raging lust for women, so common in Africa. It seems that you Europeans have only milk in your veins; but it is vitriol, it is fire which runs in those of the inhabitants of Mount Atlas and the neighboring countries.” The old woman’s account is presented as an empirically known truth that jeopardizes the received authority of the now-deceased Pangloss and his fatuous assertion that this is the best of all possible worlds.

Equiano’s life story proved just as much a text of the Enlightenment as Voltaire’s Candide, though Equiano’s is markedly less acerbic, an astonishing fact given his experiences. Equiano’s text diverges from Enlightenment thought in giving the lie to the notion of some innate intellectual or moral inferiority of Africans to Europeans, or of Black men to white men. Chapter 11 of Candide, in which the “Old Woman” relates her history, conveys standard Enlightenment ideas of racial hierarchy. “The northern nations have not that heat in their blood, nor that raging lust for women, so common in Africa. It seems that you Europeans have only milk in your veins; but it is vitriol, it is fire which runs in those of the inhabitants of Mount Atlas and the neighboring countries.” The old woman’s account is presented as an empirically known truth that jeopardizes the received authority of the now-deceased Pangloss and his fatuous assertion that this is the best of all possible worlds.

Instead of reading the fictional sojourns and sufferings of Voltaire’s world-worn characters, we read a “true account” of a real person forced into exile and bondage. Our discussion in the 1980s turned upon the fact that Equiano’s very mastery of the markers of the Enlightenment – his prose style, his concern with facts, his examination and construction of history as a source of knowledge and wisdom – undermined Enlightenment notions about who was and was not to be considered as fully capable or deserving of freedom and equality.

I suppose if we had had time, we might have read Candide and Equiano’s Life side-by-side. But the Western Culture program was not designed for a deep dive into texts or ideas (though my track was unique in having only one lecture per week and four days per week devoted to discussion sections). It was, instead, designed so that every department in the humanities and social sciences could garner some share of the instructional hours available via distribution requirements, while introducing students to a smattering of texts which were judged “worth knowing.”

Would I have been better off knowing Candide instead of Equiano’s Life? I doubt it. I have long known that a Pangloss is a purportedly knowledgeable but actually foolish optimist, without even knowing which text the name derived from, and I have long since concluded that this is absolutely not “the best of all possible worlds,” nor is what unfolds in time the result of fate or divine design but rather an outworking of human will.

Instead, Equiano’s Life was the better text to be reading and discussing in the 1980s, at Stanford or anywhere else. I didn’t know the term “subaltern,” and had not been introduced to the problem of whether the subaltern, in speaking his truth in the language of his oppressors, ceases to be who he was. Instead, I was introduced to the tension underlying Enlightenment claims about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and for whom those claims were made. Was Equiano to be regarded as “the exception that proves the rule” or as a sad reminder of how much human potential was crushed and destroyed by the depredations of slavery as the malevolent muscled engine behind the motions of modernity?

However, lest you imagine that the gifted, capable, thoughtful Stanford undergraduates of the 1980s (and the legacy admits, and the children of the very rich, who were both separate categories with less Venn overlap on the gifted/capable/thoughtful circle than one would hope) – lest you imagine that these promising young people, the future leaders of America, were united in their understanding that Equiano’s story demonstrated the injustice of slavery and the foolishness of purported hierarchies of racial intelligence, during my time at Stanford a live subject of debate that turned into egregious harassment of Black students was this question: “Could a Black man have written the music of Beethoven,” also phrased as “Could Beethoven have been Black?” This was Stanford’s variant on Saul Bellow’s infamous assertion, “If the Zulus had a Tolstoy, we would read him.” (Yes, Bellow really said that, and yes, I have the proof, all his denials to the contrary.)

From the students of the late 1980s who debated that question – or who, at the very least, were conditioned to believe that it was a debatable issue – came a whole generation of judges, lawyers, entrepreneurs, politicians, policy-makers, and professors. Some of them read Voltaire, some of them read Equiano. All of them exert some influence on American life and politics today, as movers and shakers, as voters, as parents.

What role did that required course, with its required reading list, play in shaping their views? What role did the debate over changing that course play in shaping their views? How deep a mark can any curriculum leave on young minds thirsting for knowledge, or young minds sated with the self-assurance of wealth and entitlement?

I am still learning the answer to those questions. Indeed, as a society, we all are.

I doubt I’ll find an answer in the pages of Voltaire. But I will finish the book before I check the comments on this post, just in case there is something surprising in the ending.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Welp, having finished Candide, I can make some more informed pronouncements:

1) Candide is tedious AF. If Voltaire thought the tedium was somehow necessary to convey the moral to the reader, this is yet more proof that Voltaire vastly underestimated the acuity of most of his readers.

2) I would have hated Candide as a college freshman. Instead, I knew Voltaire only by reputation, and revered him for his anti-clericalism and his secular faith in reason, as one does.

3) Despite all the “plot twists” of Candide, I honestly did not expect Pangloss’s return. So maybe I am not a particularly acute reader after all.

4) That said, I am deeply fond of the last line of the book and the philosophy behind it — though it takes Voltaire a long time to come around to the wisdom of the Preacher from Ecclesiastes.

5) All in all, though, I’m very grateful to have read Olaudah Equiano at a time when perhaps very few college undergraduates were required to do so. I wonder if more or fewer undergrads are required to read him today.