Editor's Note

For nearly two decades, I’ve taught an undergraduate Honors Course at the University of Oklahoma built around the readings in Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition. As part of LD Burnett’s series of posts rereading Hollinger & Capper, I’m doing a series of posts exploring what it’s like to teach the volumes in an undergraduate, honors setting. In my first post, I said a few general things about Perspectives on the American Experience: American Social Thought, the course (or actually courses) in which I use The American Intellectual Tradition. When I began this course, The American Intellectual Tradition was in its 3rd edition. Unless otherwise noted, I’ll be blogging about the most recent edition of the books, the 7th. In this final post in my series, I discuss teaching Volume II, Part Four, entitled “Reassessing Identities and Solidarities” For more on Volume II, Part Four, see LD’s post on it. I’ve been blogging about a new section every two weeks as LD worked her way through the book. In these posts, I have generally not been attempting to provide a comprehensive description of what I do with Hollinger & Capper in the classroom. Instead, I will usually be highlighting an aspect or two of my approach to each section. Please feel free to use the discussion thread for more general comments or questions about teaching this particular part of The American Intellectual Tradition. I’d like to thank LD for putting her series together and inspiring my parallel participation. I hope these posts on teaching The American Intellectual Experience are useful to some of our readers!

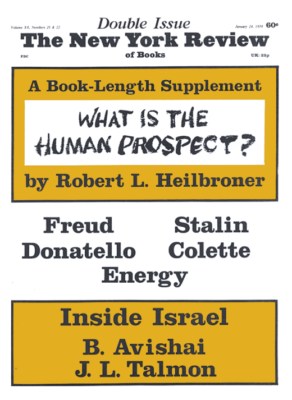

When I’ve taught the Seventies in other classes, I’ve had students read Heilbroner’s instructively pessimistic “What is the Human Prospect?” (1974). But it falls in the middle of AIT’s missing decade.

In earlier posts in this series, I’ve occasionally addressed changes that have taken place over the course of the seven editions of The American Intellectual Tradition. Some of these I’ve greatly appreciated; others I’ve liked less. But none of my preferences have been as strong as my feelings about the fourth and final part of Volume II, “Reassessing Identities and Solidarities.”

The content of this final section has fluctuated more than any other section of these two volumes. And that makes sense, for at least two reasons.

First, what seems to be significant in the past changes with the passage of time. And these changes are often more severe in relation to the very recent past. The changing readings in the Part Four of Volume II clearly reflect changes in the American scene at the time of each edition’s publication. For example, the aftermath of 9/11 and the Iraq War loomed large at the end of the Sixth Edition of The American Intellectual Tradition, which was published in 2011. Volume II, Part Four of that edition included selections from both Samuel Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations (1993) and Sam Harris’s The End of Faith (2004). I find neither of these works convincing or attractive on the merits, but both were – and perhaps are – of great intellectual significance. And it is obvious why Hollinger and Capper decided to include them in the Sixth Edition. The current, Seventh Edition, published in 2016 and reflecting the Obama era during which it was edited, removes both Huntington and Harris. Harris’s New Atheism is discussed, critically and effectively, in a new addition to the book, and the very last reading in the Seventh Edition, Philip Kitcher’s “Modern Militant Atheism.” But fears about Islam as a kind of “existential enemy” are now nowhere in sight.

But there’s a second reason why the final section of these volumes changes more than any other: as time passes, Volume II has to cover a longer period. Nearly three decades of American intellectual history now exist that did not when the first edition of AIT hit bookstores (remember those?) in 1989. AIT has dealt with this expansion of American intellectual history largely be expanding the scope of Volume II, Part Four. In the Fourth Edition, this section of the book contained readings covering thirty one years (1962 – 1992). Not only is the most recent reading now from 2011, but the beginning date of Part Four has actually moved back, as C. Wright Mills’s “Letter to the New Left” (1960) has migrated from Part Three and two more readings from that year have also been added. The result is that Section Four now covers readings from more than half a century: 1960-2011.[1]

Like the earlier sections of these volumes, “Reassessing Identities and Solidarities” is extremely rich and full of interesting material for the undergraduate classroom. But so much is covered in this section that, rather than dividing the material thematically as I do when I teach the first three parts of this volume, I divide it chronologically.

As LD pointed out in her most recent post on AIT, a peculiar and unfortunate result of the expansion of Part Four over the years has been the virtual elimination of the 1970s from the volume. Half of Part Four consists of eleven readings from the 1960s, the last being Noam Chomsky’s “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” (1967). There are then two readings from the late 1970s: a selection from Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and Nancy Chodorow’s “Gender, Relation, and Difference in Psychoanalytic Perspective” (1979). The final nine readings are a breakneck dash through 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, before finishing in 2011…though, truth be told, the 1990s are now also essentially missing. They get one reading: a selection from Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990). Of course, numerical decades are historically artificial; history doesn’t notice when years end in zero. The problem here is that, in the midst of the half century covered by Part Four, there are two decade-long lacunae: 1968-1977 and 1991-2000.

In principle, there’s a pretty straight-forward solution to these problems: expand Volume II to five

sections. Volume I already has five sections, so this would create a certain symmetry. Now I realize that there are some obvious challenges that this suggestion poses. To begin with, though it has fewer sections, Volume II is not shorter than Volume I. And I do not think that lengthening the volume would make much sense, either to the publisher or to those of us who use it in the classroom. Were this volume one-quarter again as long, I could not cover all of it in a single semester, even given OU’s overly long semesters and our extraordinary Honors students. Moreover one of the challenges of assembling Volume II is that much of its material is still under copyright, adding to the costs – and headaches – involved with producing this book.[2] And virtually anything that Hollinger and Capper add from the last half century that the volume covers will be copyrighted material that will have to be cleared and paid for.

But let’s set those practical considerations aside for a minute and think about how we might divide the overly stretched Part Four into a new Part Four and Part Five. Like LD, I notice the absence of the 1970s more than I did the absence of the 1990s from this volume. In part, this reflects the fact that the 1970s are in much clearer historical focus to us in 2018 than the 1990s are. But I think this also reflects the emerging sense among scholars that the 1970s were an extraordinarily significant watershed in American intellectual history. For example, Dan Rodgers’s The Age of Fracture sees the last quarter of the 20th century as a distinct moment in American thought and culture. Part Four currently straddles, but largely avoids, this watershed.

So in a perfect world, with no issues involving the length of Volume II or the cost of copyright clearances, I’d add ten readings from the 1970s, and include them with the readings from the 1960s in Part Four. Part Five would then pick up at the very end of the 1970s and continue to the present, with room for ten more readings to round out its coverage…and presumably bring the 1990s into sharper focus. Eventually, I suspect, most readings from the 1980s will be added to Part Four and Part Five will become distinctly post-Cold War in its chronological scope.[3]

But this isn’t a perfect world. And adding a Part Five – which I really do think would be an excellent idea – will require trimming Parts One to Four, a process that would involve many very difficult choices. Eventually, I suspect Hollinger & Capper (or whoever picks up the mantle from them when they finally grow tired of this work) may even need to reconsider using the Civil War as the dividing line between Volumes I and II.

As this post suggests, Volume II, Part Four, has always been the section of these two volumes that I feel least satisfied with. But I should stress that that dissatisfaction does not come from a sense that it could easily be done better, but rather from the fact that canonizing readings in intellectual history from the very recent past is an essentially impossible task to do well. Nevertheless, I think it is an essential task. One of the pleasures of teaching The American Intellectual Tradition to undergraduates is that Volume II ends right in the middle of my students’ own lifetimes. This connection of the past to the present is one of the joys of teaching this volume.[4] And to make that connection, it is essential that the editors continue to take the leap of faith the final handful of readings in each edition represents. They will, necessarily, never quite get it right. But the very effort is absolutely worth the cost of that inevitable failure.

Ending the volume during my students’ lives allows me to include them, during that last week of the semester, in actively considering how one goes about putting a volume like this together. I like to ask them what texts – or sorts of texts — they think ought to be part of a consideration of contemporary thought. They are not intellectual historians, of course. But they are thoughtful young people, living in America, who are interested enough in ideas to enroll in my class. And seeing American social thought as something in which they themselves are involved is the perfect way to conclude the class.

Notes

[1] Part One of Volume II appears, at first glance, to cover a similar length of time, with the earliest reading coming from 1860 and the last from 1913. But this is somewhat deceptive, as that first reading, Asa Gray’s review of Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species is a kind of prologue to this volume that officially starts in 1865. And the two 20th-century readings from Part One – Henry Adams’s “The Dynamo and the Virgin” (1907) and George Santayana’s “The Genteel Tradition in American Philosophy” (1913) are themselves largely concerned with earlier times. The heart of Part One is the last thirty-five years of the 19th century.

[2] I suspect that copyright permission issues are among the reasons that Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is no longer in the Seventh Edition.

[3] As has been the case with Part Four in the past, I suspect that the new Part Five – and also the newly reconfigured Part Four – will change to match the problems of the moment of (re)editing the new edition. For example, I’d like to think that Hollinger and Capper are already considering Hannah Arendt’s “Lying in Politics” (1971) for inclusion in the Eighth Edition. And perhaps Samuel Huntington’s “The Democratic Distemper” (1975), which once appeared in this volume but was swapped out for The Clash of Civilizations in the Sixth Edition, ought to make an appearance again.

[4] One of the new texts in the Seventh Edition is Thomas Pogge’s “Priorities of Social Justice.” Around the time this volume went to press, Pogge was credibly and publicly accused of sexually harassing a former student. Though he had been disciplined for similar reasons at his former institution, Columbia University, Yale cleared him of all charges in 2016. When I last taught this text in the spring of 2017, the Pogge case became a topic of conversation in my class. If this reading stays in the Eighth Edition, I wonder if the Pogge harassment case will warrant discussion in the introduction to it. Like LD, I suspect that Pogge is likely to go and something more directly #MeToo-related will be added.

0