Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

This post examines some of the texts in Volume II, Part Four: Reassessing Identities and Solidarities. Here are all the texts included in this section:

Wilfred Cantrell Smith, “Christianity’s Third Great Challenge” (1960)

Harold John Ockenga, “Resurgent Evangelical Leadership” (1960)

C. Wright Mills, “Letter to the New Left” (1960)

Jane Jacobs, selection from The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961)

Rachel Carson, selection from Silent Spring (1962)

Thomas S. Kuhn, selection from The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962)

Betty Friedan, selection from The Feminine Mystique (1963)

Susan Sontag, “Against Interpretation” (1964)

Herbert Marcuse, selection from One-Dimensional Man (1964)

Malcolm X, selection from The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

Noam Chomsky, “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” (1967)

Edward W. Said, selection from Orientalism (1978)

Nancy J. Chodorow, “Gender, Relation, and Difference in Psychoanalytic Perspective” (1979)

Richard Rodriguez, selection from Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez (1982)

Chandra Talpade Mohanty, selection from “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses” (1984)

Frederic Jameson, selection from “Postmodernism and Consumer Society” (1985)

Richard Rorty, “Science as Solidarity” (1986)

Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” (1989)

Judith Butler, selection from Gender Trouble (1990)

Thomas Pogge, “Priorities of Global Justice” (2001)

Barack Obama, “A More Perfect Union” (2008)

Philip Kitcher, “Militant Modern Atheism” (2011)

Well, here we are. We have reached the end of the American Intellectual Tradition– the two-volume, nine-section primary source reader, now in its seventh edition.

Whether or not we have reached the end of “the American intellectual tradition” is a different matter. Early on in this series, I suggested that we might construct or detect many traditions or arcs of thought running from America’s beginnings to our present moment. Hollinger and Capper found a through-line of sorts in the battle between religious faith and secular scientific thought, that latter tradition itself unshackled by the anti-authoritarian free-wheeling challenge of evangelicalism to upend traditional pieties and make room for new approaches.

The last section of the anthology, “Reassessing Identities and Solidarities,” runs from 1960 to 2011 – a span of time and a set of themes I might have suggested splitting differently before, but I think the long American century ended in 2016, so this makes sense now.

Still, the section divides itself rather neatly, if not satisfyingly, in two halves: the first eleven readings all date from the 1960s, suggesting a densely-packed and densely-argued decade of intellectual work. Most of the authors in the first half of this section were not primarily academics or were not addressing fellow academics.

Not so for the second half, where we see instantiated Russell Jacoby’s reading of the vanishing of the public intellectual, or at least his or her retreat into academe. Of the readings in that section, almost all come from writers or thinkers who are speaking from within academe. Barack Obama’s 2008 speech is most notable here as an example of a truly public intellectual in the older sense of the word.

But the years from 1970 to 2011, where this anthology ends, were surely no less densely-packed and densely-argued than the single decade that preceded them. Yet here the anthology mimetically reproduces the dissolution and centrifugal dislocation of the era that Daniel Rodgers has aptly named the Age of Fracture. We get two readings from the 1970s, five from the 1980s, one from 1990, and then three more readings stretching from 2001 to 2011.

Those five readings from the 1980s are a comfort to me, because they underscore the ’80s as a “heavy decade,” especially encouraging to someone who is watching at the plate for the ’80s high fastball, hoping to knock it out of the park.

But beware of the changeup pitch, the off-speed pitch. Beware of the silent 1970s. Nothing about this section bothers me so much as the long quietude from Noam Chomsky to Edward Said. Where are the 1970s? Where is 1970 itself, an annus mirabilisof radical feminism? Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, and the blockbuster best-selling anthology Sisterhood is Powerfulwere all published in 1970. For that matter, Gil Scott-Heron’s album Small Talk at 125thand Lenox, extraordinary from the first beat to the last, but noteworthy for this intellectual historian especially for “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and “Whitey on the Moon” — a title that could have stood nicely as a one-sentence review of Norman Mailer’s 1970 “non-fiction novel” ostensibly about the Apollo moon landing but really about Norman Mailer with the Apollo moon landing as the latest elaborate backdrop for his never-ending “Kvetch of Myself.”

What else would fit from the early 1970s? What about a teleplay, the script for an episode of All In the Family? In junior high school our literature reader included the teleplay (with shot descriptions and all) of the Twilight Zoneepisode, “The Monsters are Due on Maple Street.” It was a memorable text, certainly, and in the late 1970s it was being used in school curricula to shape the thought of a generation of young Americans away from McCarthyism and prejudice and toward inclusion and the solidarity of citizenship.

Rather than suggest alternate texts for this section, with the requisite labor of deciding who can go (bye bye, Thomas Pogge!), here’s a question: what is going to be added?

As we move into the latter years of this present decade and beyond, what text from our own time will seem salient, representative, characteristic, or consequential enough to characterize this current era?

Who will represent the mind-set of this era? A “Gamer Gate” apologist? Some nauseating nostrum from David Brooks, the cardboard cutout stand-in for every Reasonable White Guy who feels persecuted if he cannot entirely dominate the conversation and the culture with his own words, thoughts, preferences and opinions? Some grotesquerie from the pen of the execrable Dinesh D’Souza?

How about Rebecca Solnit’s “Men Explain Things to Me”? Some of Jane Mayer’s deep reporting on dark money in American politics? An essay from Jill Lepore?

One of the many “MeToo” testimonials that are reshaping public discourse and professional norms, even as they serve as catalysts for a gathering backlash?

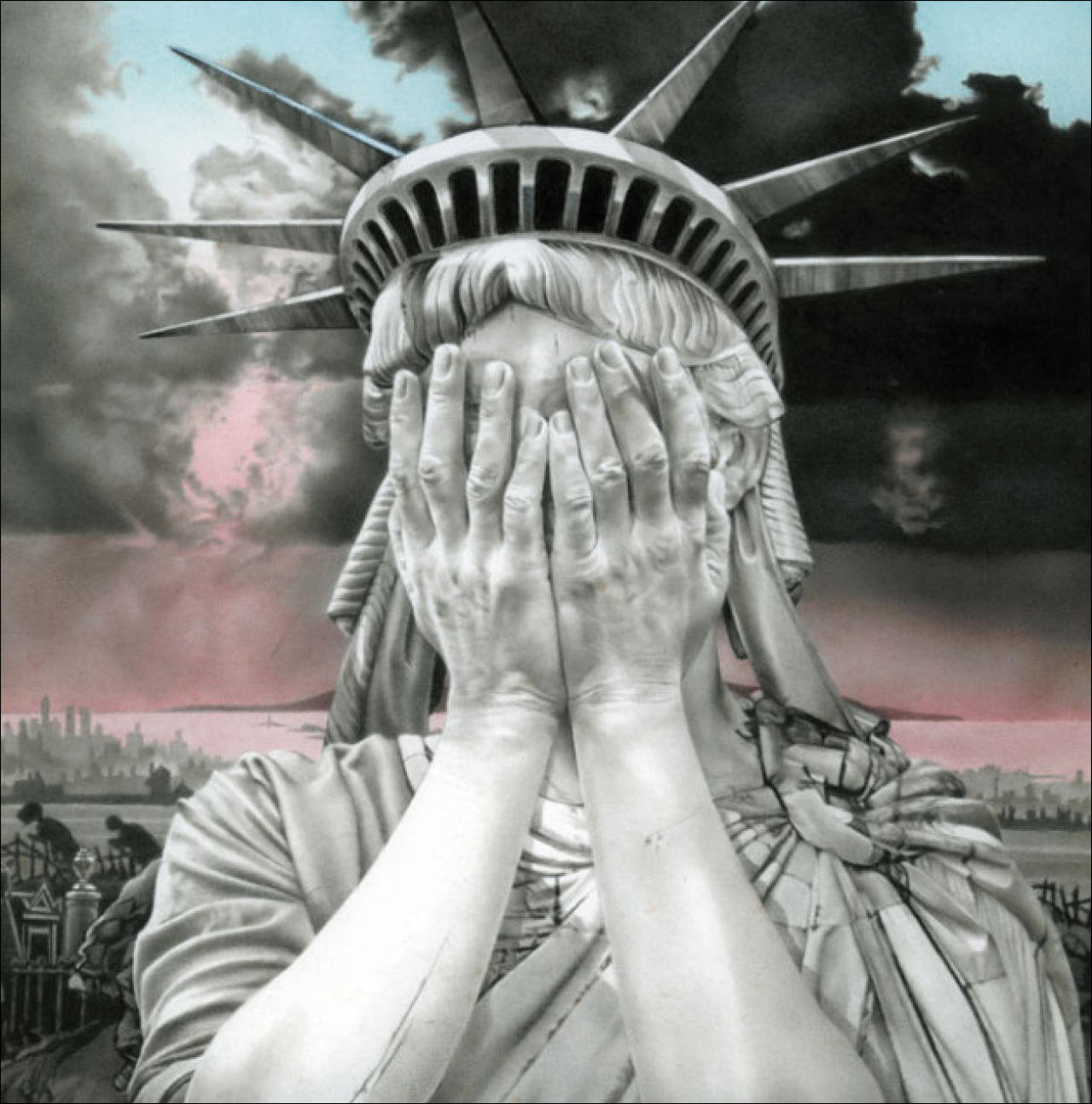

This is the age of a backlash that makes the 1980s look tame. We have Nazis marching our streets. We have Klansmen, holocaust deniers, and avowed white nationalists running for congress.

It can happen here. It has happened here.

It can happen here. It has happened here.

America never was America, but if America is going to be America again, in the mighty prayer-poem of Langston Hughes, we have a long and painful road ahead.

If I had to pick one text that stands out as the marker of our moment, I guess it would be Donald Trump’s “Escalator Speech,” where he announced his candidacy for the presidency. It was all there in germ – the racism, the nativism, the protectionism, the demagoguery. It is the raging roar of our era, and he Is its monstrous mouthpiece.

Imagine it: the American Intellectual Tradition must make room for the single stupidest, most fatuous “thinker” ever to darken the door of the White House, perhaps even the whole American scene. The ideas articulated by Donald Trump are shaping (or revealing?) the politics and public policy and moral milieu of our era. They are representative, at the very least, and what they represent is nothing very good but something very real.

The next edition of AITis going to have to include something that came out of Donald Trump’s mouth – proof enough, if proof were needed, that intellectual history is not about intellectuals or important thinkers, but solely about important ideas.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

In this vein, I think the recent Ta-Nehisi Coates essay collection, “We Were Eight Years in Power,” will make a valuable addition to the intellectual history tradition. Between each essay, he has sections where he a) talks about how his writing process evolved over time and b) how his thinking about America changed. The optimism of the early Obama years is virtually gone by the end of the collection, which is as much about Coates wrestling with (and essentially admitting he should not have been surprised by) the ascendancy of Donald Trump.

And to add to your selections above when it comes to the 1970s, I suspect when examining the 2010s historians will make note of films such as “Get Out,” “Black Panther,” and “Sorry to Bother You” which, taken together, offer some unique takes on African American thought in the modern era.

I agree with Robert. The representatives of the AIT during our current age will be Coates, Jordan Peele, Beyonce, Donald Glover, Kanye, etc., not members of the white middle class intelligencia. The centrality of these black artist-intellectuals to the current landscape of American thought makes me wonder whether the next volume of the AIT (or a revised version) should be multimedia. Perhaps the way that technology has changed our production and consumption of ideas means that a “text” is no longer the best way to explain or understand our current intellectual moment? And maybe, as a result of the democratizing impact of technology, we are living in an intellectual golden age? This is certainly a poptimistic take on our current moment – and one that, it should be noted, may be coming at the expense of engagement with older intellectual forms and participation in actions like direct political participation – but how many Americans really engaged with John Dewey or Perry Miller compared to those currently listening to Beyonce or Kendrick Lamar?

You are right. I see that I mangled the sentence in my post above where I mentioned Gil Scott-Heron. It’s more a sentence fragment than a sentence. In any case, Scott-Heron’s songs, an episode from “All in the Family,” Glover’s “This Is America” — any and all of these stand squarely within the American intellectual tradition as you and I define it…but not, significantly, as the editors of the anthology delimit it. They wanted explicitly propositional/argumentative texts. As I suggested in one of my earlier posts, this is part of the struggle to make “American intellectual history” a distinct discipline from “American studies,” which has historically had the range and freedom to consider “high and low” alike. (USIH has the freedom to do so as well, but hasn’t always shown that range.)

Another interesting problem: given the state of “the tradition” today, what different texts might we choose from the 1970s and 1980s? Do we need something by Rene Girard? A selection from Susan Faludi’s “Backlash” seems advisable. What about the 1990s? Does George H.W. Bush’s speech on “Political Correctness” need to be part of the anthology? Andrew Sullivan, not for good but for ill, remains an influential public intellectual — we have him to thank for legitimizing Charles Murray’s phrenology for the 21st century. Should Sullivan be represented in the anthology? Should Charles Murray?

I think the last 11 readings of the anthology kind of lose the plot, precisely because of their concentration within academe. The anthology should not instantiate Jacoby’s critique, because that reifies the idea that “public intellectual” is some subset of “professors,” when in fact just a sliver of the professoriate is included in the Venn overlap from a much larger and more influential group of people who are creating and articulating and promulgating ideas incessantly.

In sum, I do take issue with the insistence of Hollinger and Capper that the kind of texts they include must be explicit arguments. But I understand the disciplinary necessity of that delimitation: it becomes impossible to distinguish “the American intellectual tradition” as an object of inquiry distinct from “American culture.”

I’m not sure they need to be distinguished.

There are certain things in the post and the comments with which I agree. Having said that, I would like to offer a slightly different perspective from the vantage of someone older (by roughly a decade) than L.D. (and thus even less of a contemporary of Robert Greene and Matthew Linton), and also (I tire of repeating this but it may be necessary) of someone who is not a historian and specifically not a member of the charmed circle of scholars of U.S. intellectual history.

I agree with the suggestion that the chronological leap in this part of AIT from 1967 to 1978 is so bizarre as to border on the indefensible. However, I might suggest different (or additional) readings from this period than L.D.., who mentions 1970 as the annus mirabilis of radical feminism. The year 1970 also saw, if memory serves, the publication of Charles Reich’s The Greening of America (much of which I think had previously appeared in The New Yorker). I’m not entirely sure now of the reasons, but I read the book at the time (not really buying a lot of the argument) and also a subsequent collection of critical responses to it. Greening stirred up a lot of controversy and discussion in the non-academic general press, as did an utterly different kind of book, B.F. Skinner’s Beyond Freedom and Dignity, which appeared the following year (I think I read it in ’72, when the paperback appeared). Rawls’s A Theory of Justice also came out in 1971, but since AIT includes a Rawls piece from the late ’50s, I guess H & C can get a pass on that score.

Chomsky’s “Responsibility of the Intellectuals” (which I’ve glanced at parts of but not properly read) and Said’s Orientalism (which I haven’t read) both seem like selections that should survive any overhaul. There has to be something about Vietnam, and I guess if they’re going to impose a dubious (but perhaps necessary for space reasons) one-piece limit on the topic, the Chomsky is as good as anything. Chomsky is indirectly at least a critique of modernization theory, but there is no representative of modernization theory included, and I wonder whether the inclusion of a few pages from, say, Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth (1960) might not be indicated. (Ditch the Kuhn, I’d say, if you need to make room for it; nothing against the Kuhn, but space constraints impose these choices.)

Switching gears a bit, although I don’t think I’ve read the particular article by Pogge included here, I think H & C are right to include one reading on the general topic of global justice. If someone wants to ditch the Pogge, one alternative would be to replace him with a contemporary piece; another option would be something from an earlier work, say by Charles Beitz (e.g., Political Theory and International Relations, 1979) or Henry Shue (e.g., Basic Rights, 1980). Both Beitz and Shue, btw, are discussed extensively in Samuel Moyn’s recent Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World, a book with which I have some disagreements, but that’s irrelevant here.

I won’t address directly whether H & C’s approach of ratifying, through their selections, the Jacoby retreat-into-academe thesis is justifiable (I could see arguments on both sides of this). I am not happy btw about the fact that, apart from bits and pieces in The Atlantic, I have not read Coates, and hope to rectify that at some point. Finally, it seems to me that, not from the standpoint of ticking multicultural boxes but from the standpoint of recognizing the changing demographic face of the country and its “voices,” if one were to say that the black artist-intellectuals mentioned by M. Linton are “the representatives of the AIT in our current age,” one would need to mention some current Hispanic artist-intellectuals as well.

This is an interesting post, lots to munch on here.

For what it’s worth, I think Coates, more Didion, the first pages of the novel Jurassic Park and some pages from the middle and then the last pages from Richard Powers’ The Overstory should be in the next edition.

A carefully selected script from a thoughtful, poignant episode of M*A*S*H might work for the 1970s/1980s section. – TL