I’m happy to add to LD Burnett’s wonderful post from yesterday detailing her experience with Ebony magazine—and Vince Harding’s exhorting scholars to pay attention to it—as part of her overall research. Today I wish to add to that, demonstrating how Ebony has also played a role in my understanding of several strands of intellectual history running through the early 1970s. Considering Ebony as a place of considerable debate over African American politics, culture, and history is, as the Harding article indicated, important for anyone attempting to understand elements of the Black experience.

Before I go on to some of the fascinating debates Ebony hosted in its pages in the early 1970s, a word on Harding’s essay. I’ve written before about the importance of Vincent Harding to African American historiography. This particular essay, however, best  encapsulates Harding’s career as a historian and scholar-activist. Harding referred to “the popularizers, on what I call the evangelists of black history in the 1960s” when he spoke of the importance of both Ebony and Negro Digest/Black World to his scholarship.[1] Harding, however, does go a bit further than this—he also insists on understanding the legacy of African American history up until the 1970s. Indeed, he noted that the creation of African American history was part of “the matrix of our people’s struggle for freedom,” that it could not be divorced at all from the battle for liberation.[2]

encapsulates Harding’s career as a historian and scholar-activist. Harding referred to “the popularizers, on what I call the evangelists of black history in the 1960s” when he spoke of the importance of both Ebony and Negro Digest/Black World to his scholarship.[1] Harding, however, does go a bit further than this—he also insists on understanding the legacy of African American history up until the 1970s. Indeed, he noted that the creation of African American history was part of “the matrix of our people’s struggle for freedom,” that it could not be divorced at all from the battle for liberation.[2]

Such points should not come as a surprise to any of the readers of this blog. And, perhaps, the most important section of the Harding essay is his reminder that Ebony’s overall mission remained that of a popular magazine:

“I do not wish to give the impression that during this period the magazine gave up its regular preoccupations with eligible bachelors and bachelorettes, beautiful houses, fashion fairs and millionaire black. Not by a long shot. Still, for a time, for an exciting, fascinating time, it seemed as if a combination of African and Afro-American history on one hand and freedom movement activity on the other actually crowded these perennial favorites to the side.”[3]

As intellectual historians, we always strive to delve deeper into the lives of various minds—especially those who have been relegated to the margins of history. And in regards to recent American history—for the purposes of this essay, I’ll state from roughly 1970 until the present—there’s a great deal left to be mined from popular sources of entertainment and information about the state of different American minds.

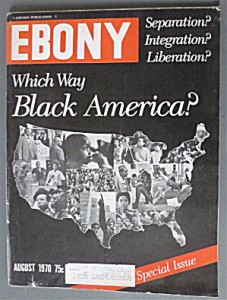

As an example, I wish to offer a brief discussion of Ebony’s landmark August 1970 issue, which included a cover story titled “Which Way Black America?” A who’s who of African American leaders argued over the direction of Black America in the immediate post-Civil Rights Movement period. What’s most interesting about this issue is that, while Black Power permeates the issue, it’s certainly not the only option discussed. In fact, this issue of Ebony is a good reminder that, when it comes to the 1970s and African American intellectual history, by no means should we focus on just the Black Power Movement. The last twenty years have seen excellent works on the Black Power Movement—William Van Deburg and Peniel Joseph come to mind of course—but we’ve also got to consider that Black Power was but one option in an era that saw many Civil Rights Movement veterans remaining active in struggle for social and political equality. Recent books such as The Challenge of Blackness and From Revolutionaries to Race Leaders remind us of the rich ideological diversity within the black community in the 1970s, but this issue of Ebony is a fresh reminder of what was being debated.

Furthermore, this issue of Ebony magazine offers definitions of key terms used to describe various aspects of African American ideology: liberation, separation, and integration. I’ll use my post next week to dive deeper into these terms, but to say this issue is valuable just for spelling out how some African American leaders perceived and defined these terms alone would be an understatement. The Johnson Publishing empire (Ebony, Jet, Negro Digest/Black World and also published books) was, in the 1960s and 1970s, at the forefront of promoting both African American history and African American intellectual debate.

Which brings me to today. I took a brief sojourn home to celebrate my mother’s birthday. I could not help but take a brief look at the stack of Ebony magazines my parents have purchased in the last year. Since I was a child, Ebony was a mainstay at home. Reading it was as automatic as reading the local newspaper. And I received my Jet fix at the local barbershop. As LD Burnett pointed out yesterday, students attending schools such as Stanford were, no doubt, exposed to big ideas about African American history through magazines such as Ebony. There’s no question I can attest to that from personal experience.

[1] Vincent Harding. “Power From Our People: The Sources of the Modern Revival of Black History,” The Black Scholar, January/February 1987, Vol. 18, No. 1, pg. 40-41.

[2] Harding, 42.

[3] Harding, 49.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Robert, thank you so much for this post. I’m really glad you brought out Harding’s aside about reading Ebony (and, by extension, any magazine) as a whole. It’s important to think about how this intellectual discourse was situated alongside and within other “slices of life.”

And thanks for concluding with that wonderful slice of life from your own experience.

🙂

Not a problem! It was certainly a treat to write!