Editor's Note

This is one in a series of posts examining The American Intellectual Tradition, 7th edition, a primary source anthology edited by David A. Hollinger and Charles Capper. You can find all posts in this series via this keyword/tag: Hollinger and Capper.

Selection 7, Part 1 of Hollinger and Capper (7th edition), is Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The most famous image from this image-packed sermon is that of God holding each of us at arm’s length in abhorrence, “much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect over the fire,” ready to drop us in. That’s not so hard to understand. Many feel the same way about the sermon.

Remember that grudge you once held against religion, from way back in your childhood, because of the way it made you feel bad about yourself or kept you up nights fearing hell? Read “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” and make that grudge feel just like new. To support this claim, I could choose a passage almost at random. But I’ll choose a few sentences from page 89 because they’re so cinematic:

And though he will know that you cannot bear the weight of omnipotence treading upon you, yet he will not regard that, but he will crush you under his feet without mercy; he will crush out your blood, and make it fly, and it shall be sprinkled on his garments, so as to stain all his raiment.

The use of fear for the purpose of persuasion; a cringing guilt that paralyzes the will; the conception of God not as loving but vindictive: “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” demonstrates in spades the offenses often laid at the doorstep of Christianity—at least this brand of it—and much ridicule has been heaped on the Calvinists, in turn. H. L. Mencken got off a few zingers, but I’m fond of the gag in the film Cold Comfort Farm, based on the 1932

Ian McKellen as Amos Sarkadder preaching to the Quivering Brethren in Cold Comfort Farm.

novel by Stella Gibbons. Out in rural England, far from the unruffled reasonableness of Victorian urbanites, gathers the Quivering Brethren, a particularly primitive Calvinist sect whose favorite hymn includes the refrain, “The Earth shall burn, but we shall Quiver.” Even those secular humanists who tolerate people of faith tend to withdraw that tolerance at such festival displays of self-loathing and timidity.

To a believer in climate science, however, and to a scholar who has taken environmental thought as a special interest, phrases like “the Earth shall burn” have an added resonance. Of all the readings in Hollinger and Capper, Part 1, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” is easily the most modern, the freshest-sounding to my ears. Take, for example, the following passage:

Were it not for the sovereign pleasure of God, the earth would not bear you one moment; for you are a burden to it; the creation groans with you; the creature is made subject to the bondage of your corruption, not willingly; the sun does not willingly shine upon you to give you light to serve sin and Satan; the earth does not willingly yield her increase to satisfy your lusts; nor is it willingly a stage for your wickedness to be acted upon; the air does not willingly serve you for breath to maintain the flame of life in your vitals, while you spend your life in the service of God’s enemies. God’s creatures are good, and were made for men to serve God with, and do not willingly subserve to any other purpose, and groan when they are abused to purposes so directly contrary to their nature and end.

This flies in the face of any assurance, commonly drawn from verses in Genesis, that the earth exists for humans to dominate. They challenge, too, assurance drawn from Francis Bacon that the earth exists for humans to exploit. When I read about the earth groaning, the images that come to mind are not those of Yosemite, Yellowstone, or Denali, or of any sublime photo from the Sierra Club calendar. I see, rather, images of heavy industrial extraction, waste-choked rivers, steaming toxic sinks and landfills–images so high on the depression quotient they’re almost too horrible to bear.

There’s nothing new in the point I’m making. The link between Calvinism and environmentalism in an American setting has been practically self-evident from the beginning. Usually, when the link is made, it’s for the purpose of derision or dismissal. Mark Stoll’s book, Inherit the Holy Mountain: Religion and the Rise of American Environmentalism is an exception. Stoll shows how, at least through the Progressive Era, enlightened policies which we would today identify as “environmental,” were conceived and facilitated by a series of Americans with roots in the Connecticut Valley and Reformed Protestantism, inspired by Calvin’s emphasis on “God in nature.” I’d like to take exception, as well, with the following question: What other works, even in today’s world, speak to the sick systemic and the posthumanist impulse as directly as the passage above?

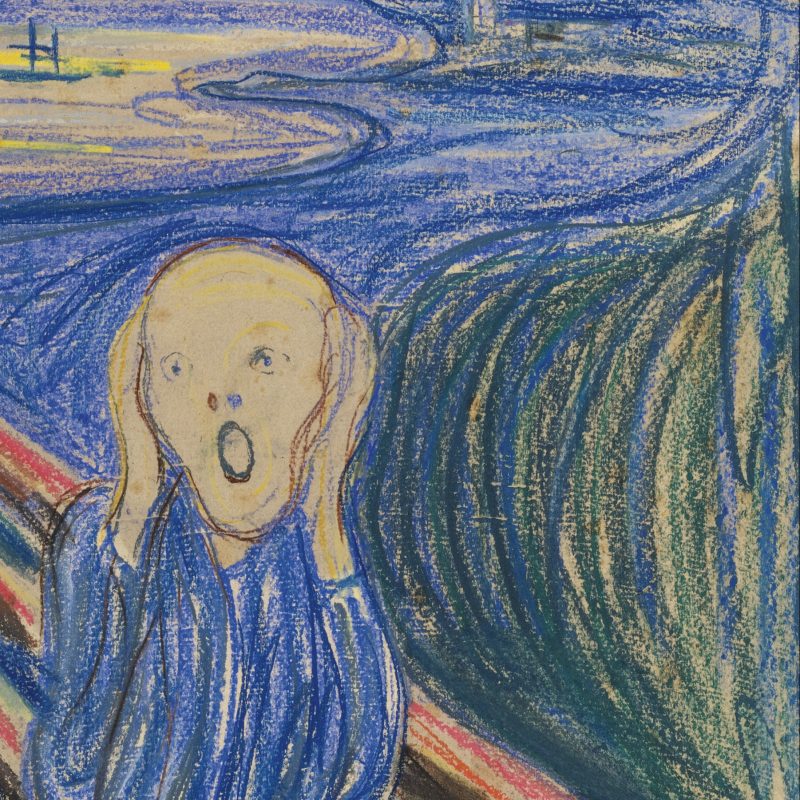

According to historian Thomas S. Kidd’s introduction to The Great Awakening: A Brief History with Documents, when Edwards preached his sermon in Enfield, Connecticut, in 1741, he had to break off from speaking because his congregants had begun to scream. So, in answer to the question above, how about Edvard Munch’s The Scream? It’s as iconic a modernist image as they come–does it strike a similar note? There are at least a couple of ways to interpret the wavy lines that seem to radiate around the figure on the bridge. They are sound waves, allowing the viewer to see how loud the screamer is screaming. We might also see them as an expression of the fact that the figure is continuous with his background; he’s blending in, he’s being subsumed, and that’s what’s causing him to scream.

question above, how about Edvard Munch’s The Scream? It’s as iconic a modernist image as they come–does it strike a similar note? There are at least a couple of ways to interpret the wavy lines that seem to radiate around the figure on the bridge. They are sound waves, allowing the viewer to see how loud the screamer is screaming. We might also see them as an expression of the fact that the figure is continuous with his background; he’s blending in, he’s being subsumed, and that’s what’s causing him to scream.

From this perspective, what’s most significant about “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” is not that it demonstrates some religious atavism, a primitive fear of supernatural beings and locations, embarrassing to us now. The point is, rather, that it illustrates a naturalism that, when one gets a glimpse of it, is no less likely to induce panic.

***

In the late 1980s, I visited a friend in Los Angeles. I picked up one of that city’s culture weeklies; I can’t remember the name. I do remember noticing that it was less like my hometown equivalent–The Dallas Observer–and more like The Village Voice, which is to say, it was thicker and included sections on books and ideas. I read a line that struck me to the heart and has stuck with me ever since. It went something like this: “If we knew how interconnected we were, we wouldn’t be able to stand it. And yet our experience is one of terrible aloneness.”

The lines illustrate a dynamic that I sense in “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” and its reception during the Great Awakening. The reality of interconnectedness is too much to stand; thus, one retreats into a more complacent isolation, which winds up being a kind of hell. What complacency is Edwards trying to penetrate? This is not a period I’ve studied in depth. I’ve read that the hysterias of the witch trials can be explained at least partially by the repressed guilt of Indian dehumanization and genocide. Some similar explanation may help us understand the hysterias of the Great Awakening. They might be understood, for example, as a deep-seated reaction to the transactional character of the errand in the wilderness as presented in another foundational sermon in the first section of Hollinger and Capper, “A Model of Christian Charity.” If we are collectively obedient, this sermon assures, we will be a model, “a Citty on a Hill.” If, however, we don’t hold up our end, we “shall be made a story and a by-word” to the contrary (15).

This theology of bargaining spurred not a few conflicts, the one with Anne Hutchinson included. In one of the documents from the aforementioned Kidd, Nathan Cole, a New England congregant, writes in 1741, “I was an Arminian until I was near 30 years of age; I intended to be saved by my own works such as prayers and good deeds.” Then he heard George Whitfield, and it changed his theology: “My old Foundation was broken up, and I saw that my righteousness wouldn’t save me.”

If theology parallels natural philosophy, here’s another connection between Edwards’ sermon and the ecological consciousness. An Arminian transaction to effect one’s own salvation is in some sense parallel to the transactions implied by a Newtonian universe wherein particular causes lead to particular effects. Edwards refutes the Arminian transaction in a way parallel to the way contemporary systems thinking refutes Newtonian causation. At the levels of complexity shared by human and eco-systemic relations, causation is not so simple and straightforward a calculation. Everything is connected; we are continuous with our environment, and therefore there is nothing we can do apart from it, nothing that doesn’t affect its systemic processes, and due to the circular character of systems, no assertions into the environment that don’t return to register our responsibility.

How different is that from the idea of a God who is always watching, always judging, and–considering the unsystemic character of the way we live–always holding us in contempt? Edwards’ version is more anthropomorphic, certainly. I’m not sure it’s any less real.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Love this essay. Great connections. Everything comes around even theology.

Thanks for this excellent post. If you’d like to explore a multimedia interpretation of Edwards’ sermon, then check out the version of it that Billy Graham preached during his “Canvas Cathedral” crusade in Los Angeles in the autumn of 1949. Easily located on YouTube, Graham’s take offers a vivid point of comparison/contrast for students to discuss, and breaks up textbook reading with vibrant audio. The Edwards Center at Yale has harvested audio clips and historical context for Graham’s iteration here: http://edwards.yale.edu/education/billy-graham.