Editor's Note

For nearly two decades, I’ve taught an undergraduate Honors Course at the University of Oklahoma built around the readings in Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition. Alongside LD Burnett’s series of posts rereading Hollinger & Capper, I’m going to be doing a series of posts exploring what it’s like to teach the volumes in an undergraduate, honors setting. In this first post in my series, I’m going to say a few general things about Perspectives on the American Experience: American Social Thought, the course (or actually courses) in which I use The American Intellectual Tradition. Next week, I’ll blog about teaching Volume I, Part One (“The Puritan Vision Altered”). After that, having caught up with LD, I’ll be blogging about a new section every two weeks as LD works her way through the book.

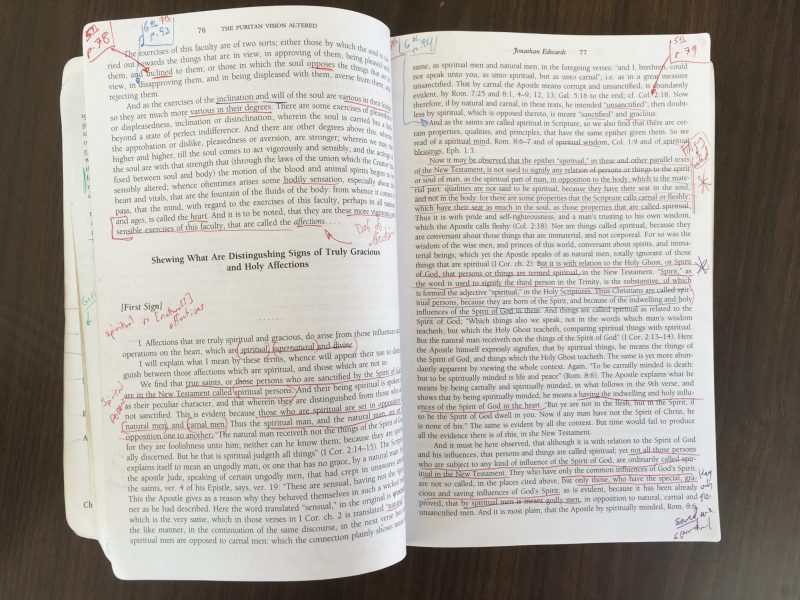

Two pages of Jonathan Edwards’s A TREATISE CONCERNING RELIGIOUS AFFECTIONS, from my copy of the 4th Edition (pub. date 2001) of Hollinger & Capper’s THE AMERICAN INTELLECTUAL TRADITION. My marginalia includes page numbers for the 5th, 6th, and 7th editions.

In 1999, about a year after I arrived at the University of Oklahoma as one of the founding faculty members of our Honors College, the College developed a new class – or really series of classes – that would be required of every Honors student and would generally be the first Honors course they took as Freshmen or Sophomores. Collectively entitled Perspectives on the American Experience, the classes were designed to be writing-intensive, interdisciplinary introductions to some aspect of American Studies (broadly understood). Back in the 1990s, team-teaching was common in the Honors College. And Perspectives was conceived as a team-taught course, with two or three faculty each bringing a different perspective on the material (hence the name).

Also in 1999, Randy Lewis, now a Professor of American Studies at UT Austin, joined our faculty in the Honors College. Randy and I developed the idea of teaching a Perspectives course that would be an introduction to American social thought through primary sources. Both because it simplified the choices we had to make and because we were both familiar with (and liked) it, Hollinger & Capper’s The American Intellectual Tradition (then in its 3rd edition) served as a starting point for syllabus. We wanted to cover the entire sweep of the American past, so we had students buy both volumes of Hollinger & Capper, used something like half of the readings in each, and added some other primary readings we particularly liked (that first time through, I think we read Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance and Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward). In its original iteration, the course consisted of an hour of lecture and two hours of discussion section each week. The class would meet together for the first hour; Randy and I then each had half the class for the two hours of discussion. The course worked very well and it quickly became a staple in both our teaching schedules. We started it with the vague sense that after teaching it a couple times, we might try to assemble our own set of primary documents instead of falling back on Hollinger & Capper. But we quickly decided not to fix something that wasn’t broken. The texts in The American Intellectual Tradition

may not have been exactly what Randy and I would have chosen were we starting from scratch. But they were rich, important, and interesting. And they spoke to each other in pedagogically fruitful ways. So the course continued using more or less the same texts with which we began.

Two things happened to it about a decade ago. First, Randy left for UT. Second, the team-taught model of Perspectives courses had waned in the Honors College and most Perspectives courses were now taught by a single faculty member. So it seemed entirely natural that I’d continue to teach American Social Thought in this new format. I’ve been doing so at least once a year ever since.

Single-faculty Perspectives courses were capped at twenty-five rather than fifty students. For reasons having to do with U.S. News rankings, this number had dropped to eighteen students by the time I began teaching American Social Thought by myself. Lecturing to eighteen students makes no sense (at least to me), so the format morphed into three hours of discussion a week, lightly guided by some introductory comments from me. Five years ago, I began distributing study questions for the next week’s readings every week. Over time I also began to eliminate the additional readings and include a bit more of the Hollinger & Capper volumes. For several years, I taught this version of the course at least once a year, often once a semester.

Then about three years ago, I had a thought that, in retrospect, seems blindingly obvious: trying to work through both volumes of The American Intellectual Tradition in a single semester was crazy. Though the course — as Randy and I had conceived it and as I had been teaching it solo for years — had worked due to the intelligence and commitment of the extraordinary students we have at OU’s Honors College, splitting the material in two made so much more sense. Not only did one course magically become two, thus making my teaching schedule more various and interesting, going slower also allowed students to explore the material at much greater depth. So, since 2016, I’ve taught one volume of the Hollinger & Capper each spring semester. In 2016, I began with Volume I. Last year, I taught Volume II, and this semester, I’m back teaching Volume I again. In this version, not only could I teach each volume cover-to-cover, but I could also add supplemental readings again; I’ll discuss what I’ve added — and why – over the next few months, as I work my way through the volumes in my blog posts. Perspectives: American Social Thought has thus gone from being a very good course to becoming two much better ones.

Some things have stayed the same through the various iterations of this course. The course requirements have been remarkably stable. We start each week with a little quiz designed simply to make sure that the students are doing and understanding the reading. The course quickly becomes impossible for students if they fall behind; the quizzes are just designed to keep them on track. In ten weeks of their choice during the semester, students also have to write very short response papers on that week’s readings. We wanted – and I want – to get the students thinking actively about the texts early in the week. And my knowing what interests them about the texts helps me craft my study plans. Over the course of the semester, students also write three short essays (these started out four-to-six pages each; they’ve been three-to-five pages since I took over the course; I may return to slightly longer essays in the future). For years, we (and I) gave out a prompt each week, keyed to that week’s readings. In recent years, I’ve started to give fewer prompts and, thus, a little less choice. Now they receive one for each part of The American Intellectual Tradition as we finish it. Finally, they write an in-class final exam.

My introduction to the course when we first meet has also stayed the same. I still work off a (now many times revised) series of notes that Randy and I drew up together nearly two decades ago. I urge my students to read the texts for their arguments. I suggest that they should be sure, among other things, to understand the author’s intent, identify his or her intended (explicit and implicit) audiences, identify the structure of the author’s argument, and evaluate the kinds of evidence he or she presents to back up his or her argument. Why would audiences of the time have found – or not have found – the argument convincing? Do the students themselves, in the 21st

century, find it convincing?

I always tell my students that I want them to read the documents as both historical documents and as living texts. And I also urge them to both respect and disrespect the texts, by which I mean they need to take the authors and their arguments seriously, but that they should also be willing to question those arguments thoughtfully.

In future posts, I’ll explore how these things tend to play out in the classroom as we work our ways through the two volumes of Hollinger & Capper.

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Sounds like a great couple of courses, Ben.

U.S. intellectual history not being my field, I’m not familiar with the Hollinger/Capper volumes, and when I say “not familiar” I mean that, as far as I can recall, I’ve never laid eyes or hands on them. I’m sure they’re very well done. That said, I’m wondering if you have thoughts about the trade-offs, if any, between the reading of selections and the reading of longer texts. In courses of this kind, I can see why selections would be the way to go, but am just wondering if you have any thoughts on that question.

The points made in your introductory remarks seem right. Beyond that, I’m wondering if you make any introductory remarks of a thematic kind. Or do the connecting themes, to the extent they can be identified, just emerge more naturally from the readings, the editors’ own introductions, etc.? Also, how much emphasis is given to the historical context of the readings and who is responding to whom among their contemporaries, and is context treated as somehow determinative (e.g., in the Quentin Skinner, if I can stereotype or oversimplify, sense) or just as something that it’s helpful to know? Maybe you’re planning to go into all this in the future posts.

Excellent comments (and questions) Louis!

Two responses:

First, though the Hollinger & Capper volumes include excerpts from larger works, a large majority of the pieces in them are shorter works rather than such excerpts. (Here‘s the table of contents for Volume II to give you a sense of this.) I agree wholeheartedly that reading a whole work is almost always better than reading an excerpt and one of the things I like about these volumes is their preference for whole works. Still, whole shorter works can’t substitute for whole longer works. But there’s only so much one can read in a week or even a semester.

Second, as I think I suggest in the above post, putting the works in their historical context is an important part of what I do with them, but I try hard not to simply confine them to that context (which is why I tell my students to also read them as “living texts”). I do think that a certain amount of context is necessary to understand any text. But I don’t believe — nor do I teach my students to believe — that context exhausts a text’s meaning in any way. And, yes, I hope to discuss the specifics of some of these things in my future posts on teaching these books.

Thanks, Ben, that’s v. helpful (esp. the table of contents link). Look forward to the future posts.

P.s. Too bad the vol 2 pb is $60 rather than $25. At $60, I have to think hard about how much I want it.

Thanks for this series, Ben, it’s always good to see what works in the undergraduate classroom. From the standpoint of teaching in public history, I’ve used volume I to distill and outline shifts in American thought and culture from the Declaration to disunion. The extracted primary sources (some of which we can show!) coordinate well with related artifacts and situate the lives of prominent early Americans in better context. I’ll look forward to your series, and I have a challenge idea for your students: Rather than an essay, how would they create an exhibit to “show and tell” aspects of the American intellectual tradition? What would a museum of American intellectual history look, sound, and feel like?

That’s a great challenge….and at the very least an interesting idea for an essay / exam question!