She had words for the wilderness, too.

She had words for the wilderness, too.

The problem with splicing together a supercut of the American intellectual tradition, as Charles Capper and David Hollinger have readily acknowledged, lies in capturing the boldness and the range of voices that we get to hear. Flipping through their first volume, which Professor Capper assigned to us in an American Intellectual History graduate seminar many semesters ago, I went looking for the women. As other contributors to this series reexamining The American Intellectual Tradition have noted, they are not easy to find. Yet in the years between Anne Hutchinson and Judith Sargent Murray, women did not fall silent. Equally intrigued by the notion that travel can shape identity and ideas, I sought out more migratory perspectives among the authors. How did America’s pilgrims document progress? What was at stake when they broke with tradition and followed new ideas across oceans and over land? With that in mind, today I nominate one Puritan woman thinker (and there are many more!) to take her place on your syllabus or museum wall: Madam Sarah Kemble Knight.

Writing her signage would be tough, for we know little of Knight’s life in Puritan Boston. Sarah Kemble was born on 19 April 1666 and she died in Connecticut on 25 September 1727. The twentysomething Sarah married Richard Knight, an itinerant sea captain, and they had a daughter. Sarah operated a boarding house/stationery shop/dame school while living on Moon Street (where young Benjamin Franklin *may* have been her student). Sometimes, as scholars report, Sarah Kemble Knight’s handwriting graced Puritan-era legal documents for cases where she served in the role of witness. But what Sarah Kemble Knight is far more famous for is getting out of Puritan Boston. In October 1704, she embarked on a solo journey to New Haven and New York, to attend to legal matters. For five hard months on the road, Sarah kept a colorful journal of her progress, itemizing her experiences alongside a vivid cache of character sketches, religious reflections, and social observations. (It’s digitized aplenty, and it’s a fairly short read, so click on through right here for a taste of Knight’s views, which comprise a mainstay of early American literary studies). She returned home to Boston in March 1705.

A woman alone on the Boston Post Road, Sarah knew she needed to move with purpose. At times, Knight was accompanied by male guides, but her trip meant a long hard slog on winter’s highway. From the outset, she seemed keen to take down field notes with the reportage instincts of a practiced correspondent. When it came to sculpting the (super)natural world on paper, she did not flinch at the vastness of the terrain, nor did she hide her fear of it. No matter the landscape, she was armed with confessions and quips. Often Madam Knight’s days of travel began before dawn and meant terror-filled crossings in worn, narrow “Cannoos” across ice-choked inlets. “I cannot express The concern of mind this relation sett me in: no thoughts but those of the dang’ros River could entertain my Imagination, and they were as formidable as varios, still Tormenting me with blackest Ideas of my Approaching fate–Sometimes seing my self drowning, otherwhiles drowned, and at the best like a holy Sister just come out of a Spiritual Bath in dripping Garments,” she wrote of one ordeal in the wilds of Kingston, Rhode Island.

A woman alone on the Boston Post Road, Sarah knew she needed to move with purpose. At times, Knight was accompanied by male guides, but her trip meant a long hard slog on winter’s highway. From the outset, she seemed keen to take down field notes with the reportage instincts of a practiced correspondent. When it came to sculpting the (super)natural world on paper, she did not flinch at the vastness of the terrain, nor did she hide her fear of it. No matter the landscape, she was armed with confessions and quips. Often Madam Knight’s days of travel began before dawn and meant terror-filled crossings in worn, narrow “Cannoos” across ice-choked inlets. “I cannot express The concern of mind this relation sett me in: no thoughts but those of the dang’ros River could entertain my Imagination, and they were as formidable as varios, still Tormenting me with blackest Ideas of my Approaching fate–Sometimes seing my self drowning, otherwhiles drowned, and at the best like a holy Sister just come out of a Spiritual Bath in dripping Garments,” she wrote of one ordeal in the wilds of Kingston, Rhode Island.

Any reader familiar with the perilous commutes of Martha Ballard, many decades later, will appreciate Sarah Knight’s struggle near Stamford, Connecticut. “Here wee took leave of York Government, and Descending the Mountainos passage that almost broke my heart in ascending before, we come to Stamford, a well compact Town, but miserable meeting house, wch we passed, and thro’ many and great difficulties, as Bridges which were exceeding high and very tottering and of vast Length, steep and Rocky Hills and precipices, (Buggbears to a fearful female travailer.) About nine at night we come to Norrwalk, having crept over a timber of a Broken Bridge about thirty foot long, and perhaps fifty to ye water. I was exceeding tired and cold when we come to our Inn, and could get nothing there but poor entertainment, and the impertinant Bable of one of the worst of men, among many others of which our Host made one, who, had he bin one degree Impudenter, would have outdone his Grandfather. And this I think is the most perplexed night I have yet had,” she wrote. New England hospitality, providential in parts, proved sparse. In her account, the warm glow of an open tavern often shone false. Knight endured her share of mistrustful owners, rowdy fellow travelers, and boiled-milk-and-molasses dinners. On evenings like those, Sarah Kemble Knight beat a hasty retreat to her room. “Poor weary I slipt out to enter my mind in my Jornal,” she wrote, then went on at dawn.

Knight broke up the diary entries with literary allusions, comments on Native Americans and African Americans, and a slew of finely shredded moral judgments on whatever she saw. So, how and why should we teach her? Read Sarah Kemble Knight’s journal because she recounts a physical and a moral trial, supplying another Puritan woman’s voice within the American intellectual tradition. Hers is a mind in transit, imprinting new experiences and struggling to see if they fit with an inherited (and rapidly expiring) Puritan worldview. Knight is a documentarian of early American manners, and her journal unfolds footage of a colonial world in flux. Long before Harriet Martineau, Fanny Trollope, or Alexis de Tocqueville launched critical tours of American morality, colonists like Sarah Kemble Knight took up the inquiry. Her views—on race and religion, men and women, New Yorkers and New Englanders—provide an intriguing contrast to those of the 19th-century reformers who star elsewhere in Hollinger and Capper’s anthology. In the classroom, Knight’s journal pairs well with Samuel Sewall’s diary and/or one of my favorite essays in early American intellectual history, David D. Hall’s “The Mental World of Samuel Sewall” (Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, 92:21-44).

Knight broke up the diary entries with literary allusions, comments on Native Americans and African Americans, and a slew of finely shredded moral judgments on whatever she saw. So, how and why should we teach her? Read Sarah Kemble Knight’s journal because she recounts a physical and a moral trial, supplying another Puritan woman’s voice within the American intellectual tradition. Hers is a mind in transit, imprinting new experiences and struggling to see if they fit with an inherited (and rapidly expiring) Puritan worldview. Knight is a documentarian of early American manners, and her journal unfolds footage of a colonial world in flux. Long before Harriet Martineau, Fanny Trollope, or Alexis de Tocqueville launched critical tours of American morality, colonists like Sarah Kemble Knight took up the inquiry. Her views—on race and religion, men and women, New Yorkers and New Englanders—provide an intriguing contrast to those of the 19th-century reformers who star elsewhere in Hollinger and Capper’s anthology. In the classroom, Knight’s journal pairs well with Samuel Sewall’s diary and/or one of my favorite essays in early American intellectual history, David D. Hall’s “The Mental World of Samuel Sewall” (Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, 92:21-44).

Finally, there’s one more way to think about Sarah Kemble Knight, and it’s more of a public history practice test. What would her intellectual history look like in an exhibit? (I asked Ben Alpers to do this with his students, so it’s only fair that I try the exercise, too). We’d want to show the original manuscript journal, but only a fragment in her hand exists. A map of the Boston Post Road might fit, some material culture to show Knight’s overland couture, and maybe a few examples of early Massachusetts legal documents or of the lex mercatoria that the well-educated Knight cited to advertise her business savvy. Part of showing Knight’s mind at work, though, is to make clear the intervention of the archive: How has her journal “traveled” through historical memory? We’d also turn to her Victorian editor, Theodore Dwight, Jr., (1796-1866), to see how Knight’s story was saved and why it became an instant classic for antebellum readers.

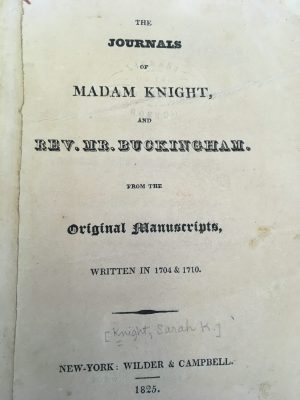

Dwight, a great-grandson of the theologian Jonathan Edwards, spun travel essays and engraved his name in American religious history by publishing Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosures, a salacious narrative of Canadian convent life, in 1836. Dwight’s approach to rediscovering Sarah Knight was more restrained, and packaged with a scholarly flourish. “This is not a work of fiction,” Dwight trumpeted in his introduction to the first edition in 1825, “as the scarcity of old American manuscripts may induce some to imagine; but it is a faithful copy from a diary in the author’s own hand-writing, compiled soon after her return home, as it appears, from notes recorded daily, while on the road.” In transcribing the (now) largely lost text, Dwight adhered to the author’s “original orthography…so far as to retain the errors of the pen, for fear of introducing any unwarrantable modernism.” Ever a canny salesman, Dwight bundled together Knight’s saga with that of Reverend John Buckingham, whose journal described the “Expedition Against Canada, in the Years 1710 and 1711.” Here is another contrast for those interested in the American intellectual tradition to discuss, with an eye on curatorial intrusion. For Dwight modernized the language of Buckingham’s journals, skipped over the enciphered bits, and slid in some historical context as prequel. In Dwight’s editorial vision of these two Puritan contemporaries, Buckingham is a godly man persevering in misadventure, while Knight is a quaintly-accented woman whose fate is keyed to Providence. Buckingham sounds modern, while Knight’s story is entombed in a bleaker (Puritan) time. How gender shades our comprehension of Puritan intellect—then and now—calls for more scholarly conversation on a complicated class of colonists. Take Buckingham’s homecoming, which is pinned primly to a single line: “I returned to my family.” At tale’s end, Sarah Kemble Knight wrote that her return to Moon Street brought “Kind relations and friends flocking in to welcome mee and hear the story of my transactions and travails I having this day bin five months from home and now I cannot fully express my joy and Satisfaction. But desire sincearly to adore my Great Benefactor for thus graciously carying forth and returning in safety his unworthy handmaid.” As Sarah Kemble Knight reminds us in her remarkable journal: In the wilderness, no two errands were alike.

orthography…so far as to retain the errors of the pen, for fear of introducing any unwarrantable modernism.” Ever a canny salesman, Dwight bundled together Knight’s saga with that of Reverend John Buckingham, whose journal described the “Expedition Against Canada, in the Years 1710 and 1711.” Here is another contrast for those interested in the American intellectual tradition to discuss, with an eye on curatorial intrusion. For Dwight modernized the language of Buckingham’s journals, skipped over the enciphered bits, and slid in some historical context as prequel. In Dwight’s editorial vision of these two Puritan contemporaries, Buckingham is a godly man persevering in misadventure, while Knight is a quaintly-accented woman whose fate is keyed to Providence. Buckingham sounds modern, while Knight’s story is entombed in a bleaker (Puritan) time. How gender shades our comprehension of Puritan intellect—then and now—calls for more scholarly conversation on a complicated class of colonists. Take Buckingham’s homecoming, which is pinned primly to a single line: “I returned to my family.” At tale’s end, Sarah Kemble Knight wrote that her return to Moon Street brought “Kind relations and friends flocking in to welcome mee and hear the story of my transactions and travails I having this day bin five months from home and now I cannot fully express my joy and Satisfaction. But desire sincearly to adore my Great Benefactor for thus graciously carying forth and returning in safety his unworthy handmaid.” As Sarah Kemble Knight reminds us in her remarkable journal: In the wilderness, no two errands were alike.

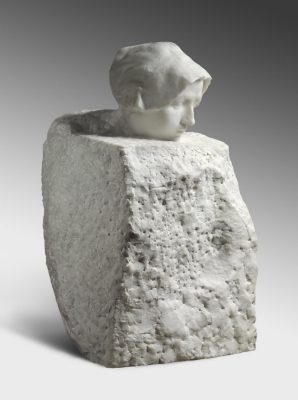

[Three views of Thought, Auguste Rodin, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Modeled 1895; carved 1900-1901].

4 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this! I was unfamiliar with Sarah Kemble Knight before your recounting. And I love your suggestions for teaching the travel journal. – TL

Just wanted to say that this was terrific–such a brilliant model of thinking through and thinking with a primary source.

Sara, thank you for this. And thank you as well for the images of the beautiful (and beautifully named) Rodin.

Thanks for the kind words, all, it’s been a pleasure to read the diverse contributions to this series. Looking forward to more!