I’ve been thinking in very broad and still tentative terms about my next major research project, which will not – so help me Clio! – focus on late 20th century U.S. intellectual history. I’m ready to roam a little bit in terms of periodization and scope; I’ve got the range for it. Besides, life’s too short to put off doing whatever it is that enlivens your mind or enlarges your soul. So I’ve been doing a little bit of off-road reading, and I’ve really enjoyed it.

Here are my picks (and pics) for the month of September.

Books I read:

Donald R. Kelley, Faces of History: Historical Inquiry from Herodotus to Herder (Yale, 1988)

Kelley is a good and trusty guide through “the Western canon” of historical writing. But I especially appreciate that he included a major section on the Byzantine historiographic tradition. Kelley explained, “In general, the historiography of the ‘second Rome may be peripheral to the Western canon under consideration here, but it does form a bridge between classical antiquity and those Christian conceptions of the human condition which would so profoundly reshape Western visions of the human past” (74).

Thanks to two intriguing paragraphs from that section of his book, I found my way to this absolutely essential read:

Thanks to two intriguing paragraphs from that section of his book, I found my way to this absolutely essential read:

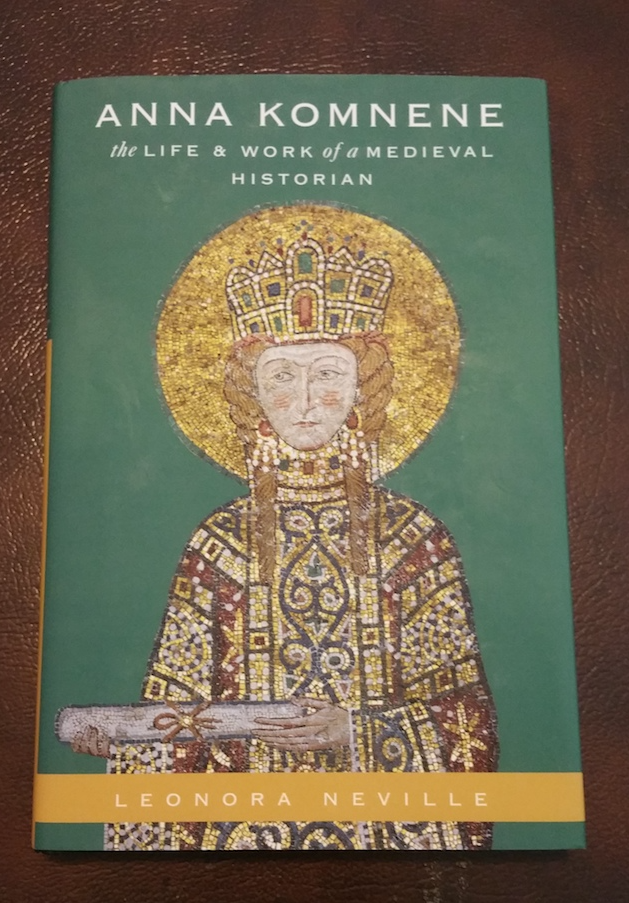

Leonora Neville, Anna Komnene: the Life & Work of a Medieval Historian (Oxford, 2016)

Anna Komnene (often transliterated Comnena) was the extraordinarily well-educated daughter of Emperor Alexius Comnenus. Anna was a witness to the First Crusade, and her account of connected events in the Alexiad, a history of her father’s reign, is one of the only such sources we have written from a Byzantine point of view.

Some later Byzantine historians and many Western scholars who turned to the Alexiad in later centuries constructed a narrative of Komnene as a Lady Macbeth-like power hungry woman who wanted to ascend to the throne instead of her brother John. But Kelley presents a riveting alternate reading that explains Komnene’s major work as a brilliantly crafted narrative that was trying to do two completely incompatible things at once: stand as an exemplary text in the long and well-developed Byzantine tradition of formal historical writing (a man’s work) while at the same time honoring and remaining within the equally well-developed expectations of what is and is not properly the work of a good woman in Byzantine culture. Given the constraints of the genre, how can a woman – even a brilliantly-educated one – claim and demonstrate masterful authority in this sphere of writing without making herself, and hence her family, disreputable?

Some later Byzantine historians and many Western scholars who turned to the Alexiad in later centuries constructed a narrative of Komnene as a Lady Macbeth-like power hungry woman who wanted to ascend to the throne instead of her brother John. But Kelley presents a riveting alternate reading that explains Komnene’s major work as a brilliantly crafted narrative that was trying to do two completely incompatible things at once: stand as an exemplary text in the long and well-developed Byzantine tradition of formal historical writing (a man’s work) while at the same time honoring and remaining within the equally well-developed expectations of what is and is not properly the work of a good woman in Byzantine culture. Given the constraints of the genre, how can a woman – even a brilliantly-educated one – claim and demonstrate masterful authority in this sphere of writing without making herself, and hence her family, disreputable?

It’s a riveting read, and I think this is the kind of book I’d assign for a “historical methods” or “historiography” course, especially the course enrolls students from various subdisciplines. This one I’d mark as a “must read” for historians concerned with the intersections of gender and historical writing. And I would note: the Byzantine era may be very far away, but some of the challenges Anna Komnene faced and tried to overcome as an author and a woman are still very much with us (yes, even with us historians), as this recent New York Times op ed suggests.

Carl L. Becker, The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers, 2nd edition (Yale, [1932] 2003)

This was a real pleasure to read. It’s not long – four lectures Becker delivered at Yale and then edited for publication. His argument, in a nutshell, is that the philosophes did not replace benighted faith with dispassionate reason, but that their reason was an impassioned sort of millennialism that sought a new heaven and a new earth, but shifted the temporal locus of those hopes from a time beyond time to a time within time. Basically, secularization has been less secular than it seems – a point he makes in his concluding chapter by considering the millennial hopes of Karl Marx. It’s a fine argument, though not an uncontested one, certainly, but it’s so lightly and lovingly made in this book.

And, for those of us who do “history of sensibilities” or “the cultural history of ideas,” one crucial passage in the second chapter bears consideration:

If we would discover the little backstairs door that for any age serves as the secret entranceway to knowledge, we will do well to look for certain unobtrusive words with uncertain meanings that are permitted to slip off the tongue or the pen without fear and without research; words which, having from constant repetition lost their metaphorical significance, are unconsciously mistaken for objective realities. In the thirteenth century the key words would no doubt be God, sin, grace, salvation, heaven, and the like; in the nineteenth century, matter, fact, matter-of-fact, evolution, progress; in the twentieth century, relativity, process, adjustment, function, complex. In the eighteenth century the words without which no enlightened person could reach a restful conclusion were nature, natural law, first cause, reason, sentiment, humanity, perfectibility (these last three being necessary only for the more tender-minded, perhaps).

If we would discover the little backstairs door that for any age serves as the secret entranceway to knowledge, we will do well to look for certain unobtrusive words with uncertain meanings that are permitted to slip off the tongue or the pen without fear and without research; words which, having from constant repetition lost their metaphorical significance, are unconsciously mistaken for objective realities. In the thirteenth century the key words would no doubt be God, sin, grace, salvation, heaven, and the like; in the nineteenth century, matter, fact, matter-of-fact, evolution, progress; in the twentieth century, relativity, process, adjustment, function, complex. In the eighteenth century the words without which no enlightened person could reach a restful conclusion were nature, natural law, first cause, reason, sentiment, humanity, perfectibility (these last three being necessary only for the more tender-minded, perhaps).

In each age these magic words have their entrances and their exits . And how unobtrusively they come in and go out! We should scarcely be aware either of their approach or their departure, except for a slight feeling of discomfort, a shy self-consciousness in the use of them. The word ‘progress’ has long been in good standing, but just now we are beginning to feel, in introducing it into the highest circles, the need of easing it in with quotation marks, that conventional apology that will save all our faces. Words of more ancient lineage trouble us more….As for God, sin, grace, salvation–the introduction of these ghosts from the dead past we regard as inexcusable, so completely do their unfamiliar presences put us out of countenance, so effectively do they, even under the most favorable circumstances, cramp our style.

In the eighteenth century these grand magisterial words, although still to be seen, were already going out of fashion, at least in high intellectual society….

–Charles Becker, “The Laws of Nature,” The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth Century Philosophers (1932)

Books I’m reading:

Montaigne’s Essays and Selected Writings: A Bilingual Edition, translated and edited by Donald M. Frame (1963)

Montaigne’s Essays and Selected Writings: A Bilingual Edition, translated and edited by Donald M. Frame (1963)

While reading Becker, who takes you back, I decided I wanted to go back a little farther even. I figured it was time to re-read Montaigne, which takes me back very far indeed: to the Renaissance Literature survey course taught by the much-admired Ron Rebholz. He taught Montaigne early in the semester, paired with Thomas Wyatt. Rebholz had edited the Penguin Edition of Wyatt’s poems – it’s a fine edition, and I still turn to it regularly. Montaigne, I had lost somewhere along the way. But given the project I’m mulling over, it seemed to me that it was time to reunite with that traveler and essay once more to meet him on the page.

Anyway, I ordered the same edition of Montaigne that we had used in that class. It arrived day before yesterday. Alas, yesterday, my annual rendezvous with debilitating strep throat also arrived, so I have been listless in my reading. However, the lovely thing about a bilingual edition (this works for Loeb volumes as well) is that you can read them lying down, and you don’t have to shift the position of the book as you turn the pages. Just pick your side – French or English, left or right – prop the book up against a pillow, and read while resting.

Surekha Davies, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge, 2016; 2017 paperback)

Surekha Davies, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge, 2016; 2017 paperback)

When I can sit up comfortably again (thank heaven for laptops!), I will resume reading this fine work by Surekha Davies, an early co-laborer on the Grafton Line. I am looking not only for an avenue of entry into the larger question that’s sort of rattling around in my head, but also (always) for a more engaging way to teach the U.S. history survey. I have used the maps and ethnographic drawings of John White to talk about the way that Europeans sought to sort out the near-upending of their whole cosmology (even as they went about upending the cultural practices and daily lives of the peoples they encountered). But Surekha’s view is broader and will help me discuss and illustrate more richly just what it meant and what it took to “make room” conceptually for the peopled worlds they encountered.

Up next (whenever it gets here!):

Anthony B. Chaney, Runaway: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness (UNC 2017)

Anthony B. Chaney, Runaway: Gregory Bateson, the Double Bind, and the Rise of Ecological Consciousness (UNC 2017)

I read this project as a bound dissertation. Anthony kindly lent me his finished dissertation, at my request, so that I could see what a well-written dissertation that had the makings of a book would look like. I was amazed, but not at all encouraged – his prose was clear and lovely. And who writes clear and lovely prose in a dissertation?! But I’m glad I read it then, and I will be more than glad to return to the 20th century to read the book that promises to be even better.

But then I’m headed back to the prose of the Renaissance and will move forward from then/there – though I will always have time for a poem or two by Thomas Wyatt. Here are two of my favorites: “My galley charged with forgetfulness” and “Whoso list to hunt…”

Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

The Komnene book sounds very interesting. Thanks!

Regarding Becker and secularization, Simon May argues in his recent book that “faith in love as the one democratic, even universal, form of salvation open to us moderns” came about because of “a decline in religious faith. It has been possible only because (italics added), since the end of the eighteenth century, love has increasingly filled the vacuum left by the retreat of Christianity.”*

I had to read Becker 10 years ago, so I remember the basic thesis.

However, since I’ve forgotten some parts (and it’s fresh in your mind), in terms of specific contemporary concerns that Becker explicitly or implicitly points to, does he also hint at the notion that all human existence abhors a vacuum in this area (longing to sacralize time, space, or otherwise)? I’d love to reread this sometime because of the implications it might have for the framework of my dissertation. Is there anything in Becker’s book that would be helpful for answering this question?

The Davies book looks interesting. When I was teaching the American History survey courses, I relied on Lewis Hanke’s Aristotle and the American Indians (Indiana University Press, 1959), a short but succinct exploration of the debate over whether Native Americans had souls. It helpfully focused on Las Casas’s and Sepulveda’s ideas (I ended up creating a whole lecture based on Hanke’s book).

Anthony Chaney’s book is definitely on my list. . .

*Simon May, Love: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 1.

Mark, thanks for the comment.

Becker’s argument is that the philosophes were not the first generation of secular thinkers so much as a last generation of Christian thinkers — that they were not a generation of skeptics, but a generation of believers. And empiricism or common sense or German spiritualism were not “substitutes” for faith in the ultimate redemption of the world and humankind from suffering and evil, but were means of bringing those about. Becker doesn’t make any claim that this intellectual movement represented some kind of theologically orthodox Christian thought — indeed, these thinkers shared an aversion to any idea of something like “original sin.” So I guess Becker could have framed this as a “schismatic” or even “heretical” movement — Pelagianism for the 18th century — but his concern was rather to emphasize the way that a specifically Christian eschatological hope and sense of the fullness of time had shaped the vision of the philosophes. There’s less a substitution of “reason” for “faith” than there is a transposition of the eschaton from something beyond time to something within it. Becker ends with a consideration of the Russian revolution and raises again the question that framed the beginning of his talks — is this development a further “progress” toward a final end (the fulness of time, the fulfillment of the process of history), or is this (and, by extension, the Enlightenment, and everything else), just another cyclical oscillation between hope and hopelessness.

The Becker book is one of my favorites. I’ve also read the Chaney book way too many times, both in its dissertation and book versions. Let me assure you that these are very different versions! Rumor has it that Chaney is looking for all extant versions of the dissertation for the purpose of shredding them.

Currently reading: Good Booty, Ann Powers. Learning to Die in the Anthropocene, Roy Scranton. The Patterning Instinct, Jeremy Lent.

Anthony, your book arrived today. It’s a real thing. It’s so much more real than any draft that preceded it that I won’t even have to think about the ways it is different, because it is Itself.

Congratulations, my friend.

(But as for me, hélas, I fear that once again you have made it look all too easy.)

Some brief thoughts on Montaigne here. He strikes me as a kind of lynchpin figure — I mean, that’s surely one reason Kloppenberg begins with him — precisely because he doesn’t neatly fit. He’s transitional, it seems to me, but also kind of “loaded” in terms of much later and more full developments of thought. He might have made a good Pragmatist if he had been born 300 years later. Instead, he helped to make them.

That last passage from Montaigne about acceptance of “natural pleasures” prompts me to wonder, before shutting off the computer for the day, whether someone has written a history of ideas about pleasure. I’m sure the answer is yes; I don’t mean so much a cultural history of the notion, though that’s doubtless been done too, but rather a survey of philosophical, theoretical, or quasi-philosophical thought on it.

One might posit a crude attitudinal spectrum running from, say, an Augustinian emphasis on renunciation of (merely) physical pleasure to the celebration of sex and eros (of all varieties) in modern and contemporary culture, be it high literary fiction, movies, or pop music. And somewhere on the spectrum would be the classical Greek attitude, which (at least per Foucault, The Use of Pleasure) gave an important place to self-mastery, in the sense of freedom from ‘enslavement’ to pleasures. Add Freud on ‘the pleasure principle’ and ‘the reality principle’, season to taste, and throw the whole thing in the microwave for ten minutes (sorry, it’s late here).

Well, in the very unlikely event this book hasn’t been written already and someone proceeds to write it, I’ll take a cut of the royalties.