Editor's Note

Cedric Johnson is an associate professor of African American Studies and political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is the author of the book Revolutionaries to Race Leaders and editor of The Neoliberal Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, Late Capitalism and the Remaking of New Orleans. His work has appeared in Jacobin, Souls, Catalyst, and Journal of Developing Societies.

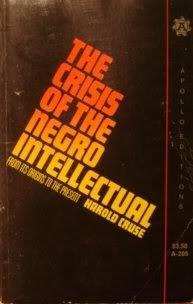

Daniel Geary’s recent blog post (“Not a Classic” 9/18/17) criticizes Harold Cruse’s 1967 book, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual as bad intellectual history. He accuses Cruse of doing something he had no intention of doing, however, and in the process, Geary fails to offer much background and insight regarding Cruse’s motives for writing the book, why it was so widely read and hotly debated at the time, and what impact it had on African American politics and letters in the years after. In other words, Geary does not approach Cruse’s work with the seriousness and attention to historical context he’s offered in his writings on C. Wright Mills and Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

As some have noted in the comments section to Geary’s post, Cruse did not craft The Crisis as intellectual history. It’s safe to say that in early 1965, when Cruse first signed a contract with William Morrow to produce two books, an original monograph and a compendium of his essays, he didn’t have any ambition of becoming an academic. Why then would he have been preoccupied with the norms and expectations of intellectual historiography? Professional historians were not his target audience. He wrote the work as polemic, one  that was deeply influenced by his time in the Communist Party and as such adopts the tone of memoir, political essay and manifesto at various turns. As Cruse admitted, The Crisis was “premeditatively controversial.” “I quite naturally anticipated that I would be in for some rather heated counterattack from even certain Blacks (and whites) who were not mentioned in my protracted polemic” he later wrote, “It was my conviction that Black social thought of all varieties was in dire need of some ultra-radical overhauling if it was to meet the comprehensive test imposed by the Sixties.” His intention was to reorient black politics in a more nationalistic direction, i.e. a politics focused less on civil rights and the attainment of middle-class consumer life, and instead on collective ownership in the realm of mass culture.

that was deeply influenced by his time in the Communist Party and as such adopts the tone of memoir, political essay and manifesto at various turns. As Cruse admitted, The Crisis was “premeditatively controversial.” “I quite naturally anticipated that I would be in for some rather heated counterattack from even certain Blacks (and whites) who were not mentioned in my protracted polemic” he later wrote, “It was my conviction that Black social thought of all varieties was in dire need of some ultra-radical overhauling if it was to meet the comprehensive test imposed by the Sixties.” His intention was to reorient black politics in a more nationalistic direction, i.e. a politics focused less on civil rights and the attainment of middle-class consumer life, and instead on collective ownership in the realm of mass culture.

Geary is right to condemn the limitations of the integrationist-nationalist dichotomy Cruse abides, but as crude as this heuristic may appear to contemporary academic eyes, it reflected relevant interpretative and political conflicts at the time. The book surfaced at a moment when various black publics were veering towards more extensive commitments to black power militancy. Even some civil rights organizations, like the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality, which were previously committed to interracialism as political practice and social ideal, were in the process of purging whites from their ranks. And perhaps most significantly, The Crisis lands during a phase of substantial investment in black urban leadership recruitment and infrastructure through the Community Action Program and other Great Society initiatives. In fact, Cruse expresses skepticism of these liberal efforts in The Crisis when referring to Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU), warning that “the Anti-Poverty program is able to buy off all the ghetto rebels with consummate ease.” Geary’s reading ignores the real historical debates and actual stakes that animated Cruse’s writing.

There’s much to disagree with in The Crisis, and I for one think the book has reaped a bitter harvest, one that many continue to sup on despite the harm it does to our understandings of politics and culture. Cruse’s arguments legitimated an elite-driven, conservative black politics predicated on the myth of ethnic pluralism. To this day, in academic writing and popular understandings of black politics, many continue to share his view of the black population as a stable, cohesive constituency, with shared worldview and interests, a perspective that papers over the complex and internally-contradictory nature of black political life.

On a related front, his musings on cultural appropriation and the need for black ownership continue to define how many view black cultural production, even as the mass culture industry Cruse confronted in the middle twentieth century has become more diversified and fragmented. Upon returning from World War II, Cruse struggled to find success as a playwright, and in his estimation, his travails stemmed from a Manhattan theatre industry reluctant to accept Negro writing that wasn’t geared towards integrationist sensibilities—hence, his disdain for Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun and The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window. As he searched for venues to workshop his plays during the early fifties, Cruse also took courses in television production and submitted applications for employment at numerous stations in the New York area.

Taking his personal aspirations and experiences in the culture industry to heart, you can see why he stakes out such a strong position in The Crisis regarding the need for greater compensation and control for black artists who were being either ignored or ripped off by Broadway, Hollywood and music industry executives. Still, Cruse’s arguments are anchored in a proprietary notion of black culture that obscured the contradiction between culture as dynamic, lived-historical experience, which cannot be reduced to racial affinity, and as those discrete practices and artifacts that might be commodified for market exchange and profit-making. Cruse thought that the problem was not commodification per se, but rather who benefited financially. What was needed then was more black ownership and artistic control, which he believed might have importance for the race writ large in terms of economic independence and recognition. We can hear echoes of Cruse’s arguments regarding cultural appropriation—albeit distorted ones— in recent protests at the Whitney Biennial demanding the removal of a white artist’s depiction of the civil rights martyr Emmett Till’s corpse, in calls for African Americans to support Nate Parker’s 2016 film The Birth of a Nation as some act of protest, and in incessant debates over hip hop music and black authenticity.

In the fifty years since its publication, we should read The Crisis now, not as anybody’s intellectual history, but as an ideological Rosetta stone of post-segregation black politics. The contextual details Geary misses regarding the landscape of sixties black politics and debates over liberal integration are hidden in plain sight, and have been written about extensively. We should continue to criticize the shortcomings of The Crisis, but that task should at least begin with some basic understanding of the historical context of the book’s creation.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

I really appreciate this thoughtful response. I set out in my own post simply to judge Cruse’s work as intellectual history and assess whether or not Christopher Lasch’s pronouncement that Crisis was a “monument of historical analysis” held up. To me, it held up surprisingly poorly. Certainly, there are other ways to read Cruse, and maybe he never meant to be read that way himself (though he has been by others). But I agree that Cruse an important figure for his time and should be understood as such and I learned a great deal about this from Cedric Johnson here.