Editor's Note

Stephen Whitfield is professor emeritus of American Studies at Brandeis University. His ten books include A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till (1988) and The Culture of the Cold War (1991, 1996).

The official website of Robert A. Caro isn’t shy about quoting the Sunday Times (UK), which calls him “the greatest political biographer of the modern era.” Even as readers await the fifth volume of The Years of Lyndon Johnson, the claim cries out for perspective and comparison.

Admittedly no such incontestable primacy is possible for any biographer. The criteria are too debatable and the unlikelihood of a single biographer atop Olympus too obvious. Yet the case for Caro looks strong.

The Path to Power (1982), Means of Ascent (1990), and The Passage of Power (2012) all won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and Master of the Senate (2002) got a Pulitzer Prize as well as a National Book Award. In 2006 the American Academy of Arts and Letters gave Caro the Gold Medal in Biography, and a decade later he won the National Book Award for Lifetime Achievement. In 2010 President Obama gave Caro the National Humanities Medal and mentioned that, as a 22-year-old, he read the honoree’s first biography, The Power Broker (1974), and was “mesmerized.” Subtitled Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, it won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography as well as the Francis Parkman Prize, bestowed for literary excellence in the presentation of the past. At the end of the century, when the Modern Library conducted a poll to identify the hundred greatest works of nonfiction of the previous hundred years, The Power Broker made the list.

Two years after The Power Broker appeared, he began his research for his second project. Because the Princeton-educated Caro is not an academic, no graduate students have helped him. His only assistant has been his wife Ina, who was sixteen years old when they met; he was nineteen. He expected to write one volume. But so exponential has been the growth of The Years of Lyndon Johnson that the third installment, Master of the Senate matches the length of the two previous volumes combined. It is as thick as the printer could bind the 1,167 pages into a single volume. Caro takes no shortcuts. The Path to Power (1982) required him to spend six years researching and describing Johnson’s first 33 years, from birth in 1908 until defeat in a Senatorial primary race in Texas in 1941. Means of Ascent (1990) covered the next seven years of Johnson’s life, but Caro needed eight years before that installment was published. Johnson spent twelve years in the Senate — exactly as long as Caro took to complete Master of the Senate. The Passage of Power (2012) needed 736 pages of text to get from the nominating convention in the summer of 1956 to Johnson’s State of the Union address in January 1964. Caro’s publishing schedule has thus barely kept pace with the arc of Johnson’s own career. At the age of 64, the ex-President was still far from elderly when he died, only four years after leaving office.

Caro’s website invites comparison with other biographers. Consider David McCullough (1933-2022). The Yale-educated historian won two Pulitzer Prizes for Biography. Both of his subjects were Presidents: Harry Truman (1993) and John Adams (2002). Both books became HBO television adaptations. McCullough diverged from Caro, however, by showing unstinting admiration for the Presidents whom he portrayed. McCullough found few dark threads — or perhaps he picked Presidents whose careers showed few dark threads. He also won two National Book Awards, in 1978 for a volume on the building of the Panama Canal (The Path Between the Seas) and four years later for Mornings on Horseback, exploring the early life of Theodore Roosevelt. In 2006 George W. Bush presented McCullough, a Republican, with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. McCullough’s book on the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, The Great Bridge (1972), also made the Modern Library list of the century’s greatest works of nonfiction. His oeuvre could be described as readable rather than controversial; and his stature was enhanced when Ken Burns picked him to narrate the nine-episode PBS series, The Civil War, which premiered in 1990. McCullough eventually narrated seventeen television documentaries. For such vocal assignments, Caro is unsuitable, because his New York accent is too thick. Instead of “time,” he says “toime”; instead of “fine,” he says “foine.”

Perhaps the sharpest contrast between the two authors, however, is that McCullough claimed to choose topics because he wanted to learn about them. So boundless was his curiosity about the nation’s past that he published about three times as many books as Caro, who has instead believed in one topic — that “it was important to explain political power.” That has been his sole focus — so much so that Caro once told an interviewer: “I wasn’t interested in writing a biography but in writing about political power.” Though he has not refused to accept awards for biography, “the basic concern in all my books,” he declared, “is how political power works in America.” That subject was not narrowly construed. Caro realized that he “would have to write not only about the powerful but about the powerless as well — would have to write about them (and learn about their lives) thoroughly enough so that I could make the reader feel for them, empathize with them, and with what political power did for them, or to them.” Indeed, to believe that absorption with the techniques of power has motivated Caro does him a serious injustice. He has wanted show “what power does to people,” and with great poignancy and compassion he has traced how the misuse of power has affected the powerless.

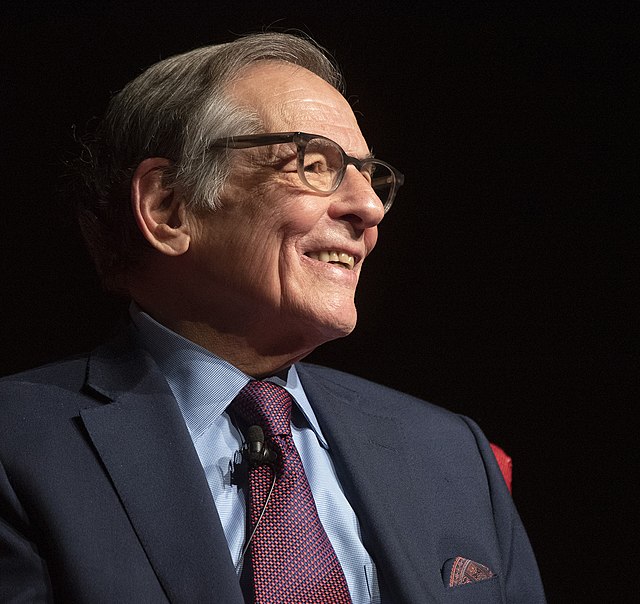

Robert Caro 2019. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

If Caro has had another serious rival — that is, someone who churns out best-sellers that are honored for their assured grasp of the American past, it would be Ron Chernow (1949- ). His first book, The House of Morgan (1990), won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. His sixth, Washington: A Life (2010), won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography. Chernow also published biographical studies of John D. Rockefeller, Ulysses S. Grant, and the Warburg family — all of which made quite easy the decision of the American Academy of Arts and Letters to bestow upon him its Gold Medal in Biography. But Chernow is best known — and undoubtedly much wealthier — because of Alexander Hamilton (2005). It is impossible to think of that best-seller without instinctively connecting it to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical, which redefined that genre. Another widely-read free-lancer was Barbara W. Tuchman (1912-1989), who won Pulitzer Prizes for The Guns of August (1962) and for Stilwell and the American Experience in China (1971). Her virtuosity was evident in her books about fourteenth-century Europe and about the American Revolution. These volumes demonstrated a breadth that also hints at Caro’s singularity. He has chosen depth. The impact of these biographers suggests that readers are living in an especially vital era of reconsideration of the key personalities that shaped the American past. But Caro stands out because his books are designed to illustrate and amplify a single theme.

Perhaps the only relevant antecedent to what Caro has done is Abraham Lincoln by Carl Sandburg (1878-1967). Its enormity and fame are evocative enough to suggest a comparison. Both authors were newspapermen before they turned to biography. Neither biographer was trained as a historian or ever held an academic position. Such is the brevity of American history that, when Sandburg was growing up in Galesburg, Illinois, he knew townspeople who remembered hearing Lincoln orate. Sandburg gained early acclaim for his poetry, which won him two Pulitzer Prizes. But his publisher, Harcourt, Brace, wanted him to inspire young readers with a four-hundred-page book about Lincoln’s boyhood and youth. Instead, the draft that Sandburg submitted in late 1924 ran to about 300,000 words. Harcourt reacted by publishing a two-volume, 962-page set, entitled Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years (1926), which his own biographer, Penelope Niven, called “a vast, epic prose poem.” Sandburg denied that he was a historian, and indeed he didn’t use footnotes or endnotes. “He conjectured,” she noted. “He used apocryphal stories, put words into Lincoln’s mouth, thoughts into his head.”

Perhaps because of these emanations from the realm of imaginative literature, the critic Malcolm Cowley declared that The Prairie Years “belongs with Moby Dick and Leaves of Grass and Huckleberry Finn.” Sandburg even fell for a literary hoax, consisting of fake letters that young Lincoln sent to Ann Rutledge. Sandburg regarded them as “entirely authentic,” until he was forced to apologize. To be sure, the incomplete scholarship of the 1920s on Lincoln would have handicapped any biographer of that era. Not until 1953 did The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln appear, and about a quarter of its pages consisted of newly published documents. To Sandburg’s readers, however, the limitations of The Prairie Years probably didn’t matter; the two volumes flew off the shelves of bookstores.

For Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939), Sandburg was better prepared, getting help from professors like James G. Randall of the University of Illinois and Allan M. Nevins of Columbia University. Sandburg also tried to appreciate the secessionist perspective by talking to Southern writers like Allen Tate, the poet who wrote “Ode to the Confederate Dead” (1928). So that Sandburg might convey the ambience of the White House, President Roosevelt gave him a personal tour in 1937. The War Years appeared as a four-volume set on December 1, 1939, crowning over two decades of collaboration between the author and his publisher. On December 4, Sandburg made the cover of Time magazine.

A wary Charles A. Beard, the most important American historian of his generation, addressed the problem that Sandburg’s opus presented: “Strict disciples of Gibbon, Macaulay, Ranke, Mommsen, Hegel or Marx will scarcely know what to do with it.” Beard nevertheless hailed Sandburg’s “indefatigable thoroughness” and predicted that his work would endure as “a noble monument to American literature.” (Beard didn’t say: American “learning.”) Columbia University’s Henry Steele Commager showed similar ambivalence. The volumes were “not primarily a work of scholarship,” yet Sandburg’s poetic gift made his “the greatest of all Lincoln biographies.” In 1940 The War Years won the Pulitzer Prize for History. Lincoln was of course the Great Emancipator. But readers may have been drawn more to his mystical nationalist creed, when the Third Reich and its allies were dangerously poised to conquer so many peoples. Democracies no longer seemed imperishable. In 1940, when Harvard awarded Sandburg an honorary degree, he was cited for writing a timely “epic that fortifies the national faith.” The ominous shadow of the European crisis helps explain why The War Years is less lyrical — and is closer to reportage — than is The Prairie Years.

Sandburg’s status in historiography then seemed secure. In 1948, when David H. Donald published his first book about Lincoln, Sandburg provided the introduction. General readers were once likely to think of him before thinking of any other biographer of the sixteenth President. In February 1959, on the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth, Sandburg spoke to a joint session of Congress to honor the occasion. Behind him on the dais sat Sam Rayburn of Texas, the Speaker of the House, as well as the Senate Majority Leader, Lyndon Johnson. Since then, Sandburg’s authority on the antebellum era and the Civil War has largely evaporated. Indeed, only three years after his commemorative speech on Capitol Hill, Edmund Wilson mounted a nasty attack. In his own book on the Civil War, the eminent critic admitted to “moments when one is tempted to feel that the cruelest thing that has happened to Lincoln since he was shot by Booth has been to fall into the hands of Carl Sandburg,” whose six volumes Wilson sometimes found “insufferable.” He would have considered them “more easily acceptable as a repository of Lincoln folklore if the compiler had not gone so far in contributing to this folk-lore himself,” by making the President into “a backwoods saint.” Wilson’s book stemmed from an extensive meditation on the cost of both preserving the Union and abolishing slavery. The withering dismissal in Patriotic Gore helped torpedo Sandburg’s reputation.

The fate of Sandburg’s once-acclaimed hagiography testifies to the vagaries of taste and to the inevitable shifts of critical judgment and scholarly knowledge. Such revisions constitute a warning that no one can foresee the durability of Robert A. Caro’s own mammoth biography, which has been accused of the opposite problem — excessive harshness — from which Sandburg’s volumes suffered. No one can foresee whether Caro’s readers will be situated in the academic community or outside of it, or both. In the very year that The Power Broker won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, Dumas Malone of Charlottesville, Virginia won the Pulitzer Prize for History with his Jefferson the President: Second Term (1805-1809). It was the fifth of Malone’s six volumes about the nation’s third President. This biography totals over three thousand pages. Having published it over the course of a third of a century (1948-82), he demonstrated the sort of doggedness that resembled Caro’s. Malone lost his eyesight in 1977 but heroically continued working on the final volume for five additional years. His work is indispensable to historians, even as their interest has shifted to focus on Jefferson’s place in the tragic legacy of slavery and race.

Will The Years of Lyndon Johnson have struck the right balance, posed satisfactory answers to the right questions? Caro’s anticipated fifth volume may help readers to reach such judgments. But let his late editor at Alfred A. Knopf take a stab at prophecy. “These books will live forever,” Robert Gottlieb predicted. “We all know that.”

0