Editor's Note

This is part 9–and the last post–in my series on Lauren Lassabe Shepherd’s Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & the Campus Wars in Modern America. You can find past posts at this link.

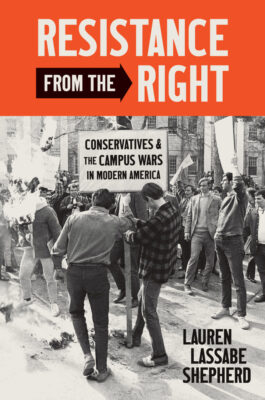

This is the cover of Shepherd’s *Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & Campus Wars in Modern America*. It shows male students protesting against Students for a Democratic Society by burning an SDS effigy at Harvard in 1969.

When I first conceived of this postscript the aim was to consider deplatforming and cancel culture. Once I started writing, however, cancel culture receded into the background. It is too big of a topic. It also involves importing too much present-day language and circumstances into the history I cover. Deplatforming also risks presentism. The term came into the English language relatively recently. It was created well after 1965-70—in 1998, per Merriam-Webster. Even so, it at least fits better conceptually into what happened in the time frame Lauren Lassabe Shepherd covered in Resistance from the Right. Deplatforming applies well enough to be a past-present bridge.

The spectacle around controversial campus speakers is a central piece of Shepherd’s work—i.e., how they draw attention, through the demonstrators, the intentions of those who invite them. For demonstrators and protestors, it is their chants, drums, bullhorns, and the din of a human gathering that fills our senses. We cannot help but notice. Given the real and perceived power of faculty and administrators, the creation of a spectacle feels like the only way, at times, for ignored or disempowered students—assumed to be ignorant supplicants—to generate action and foster change. There is power in political theater. It is a power, however, with vectors running in sometimes unexpected directions.

Resistance from the Right begins with a story about the apparent deplatforming of a controversial campus speaker. There are speaker events and demonstrations woven into every chapter. In Part 3 of this blog series I outlined, for instance, how campus conservatives integrated humor into their theatrical counter-demonstrations. Satire was part of their political theater. In today’s reflection I focus on the premeditated and planned aspects of their public campus spectacles.

Even though I do not focus today on the notion of cancel culture, it is related to deplatforming. The phenomenon of cancel culture transcends higher education—occurring in journalism, all levels of politics, celebrity culture, Hollywood, and beyond. It seeks to punish extra-legally through the destruction, or radical reduction, of one’s public presence. Cancel culture goes beyond shaming in that it can, and often does, affect one’s material well-being. It may involve the loss of a job or livelihood. On campus, however, it consists of a variety of negations that coalesce around “deplatforming.” It involves disinviting commencement speakers, shouting down campus lecturers, etc. It could also mean, educationally, the general, soft removal of one’s presence from the curriculum.

Shepherd opens Resistance from the Right at Dartmouth College in May 1967. George Wallace, the former Alabama governor and now presidential candidate, had been invited to speak. A hall with the capacity of 1400 was filled, and another estimated 1000 outside to listen to a concurrent broadcast. Inside the hall, members of Students for a Democratic Society and the Afro-American Society had obtained tickets in order to shout down Wallace. Their mission would be successful. Courtesy of their boos and “Wallace-Racist” chants, Shepherd relays that he could not be heard. Wallace sympathizers in the audience conducted a counter-protest, yelling “shut up!” and “get out!” When the crowd outside “broke past police barricades” and into the hall, Shepherd tells us that Wallace’s Alabama state trooper escort (yes, they were with him in New Hampshire) then removed him from the venue (p. 1).

The thing is, Wallace wanted this outcome. The reaction was choreographed. He desired the “spectacle of dissent” in order to play the victim. He could then blame disorder in higher education and its leftist students for America’s problems. Wallace wanted to claim that leftists and proponents of equality and peace were intolerant and violent—the true enemies of nation. By provoking hostility and hate (e.g., “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!”) he could make larger political points about the viability of conservativism (p. 1-2). Law and order were made desirable in this context. De-platforming Wallace strengthened his cause.

Shepherd outlines elements of this kind of choreography later in the book when discussing the work of the College Republican National Committee’s Executive Director, Morton Blackwell (p. 142-143). In a research coup for Shepherd, she found College Republican organizing manuals on “Public Programming” and “How to Present a Public Program” (p. 225n27-38). In addition to outlining logistical basics for on-campus speakers (e.g., booking flights, pick up crews, hotels, lunches, dinners, meeting faculty, photography, receptions), Blackwell providing venue staging tips and tactics (p. 144). This were things get juicy and interesting.

Blackwell’s venue choreography—or the CRNC’s guidebook on the same—consisted of several manipulative elements for College Republicans. Shepherd relays, it seems, almost all of them (p. 144):

- Make sure the room is too small. The planner should come up with realistic attendance number and then reduce it by twenty percent (!). The room should be packed to overflowing. A packed room created the possibility of better journalistic coverage. To help with illusion of crowding and excitement, chairs should be removed.

- Be sure to promote the event as “controversial.”

- Double the marketing coverage such that students see multiple flyers about the speaker across one’s campus.

- Campus conservatives should request that faculty make attendance mandatory for a class.

- If one can get professors to make speaker event mandatory, push them have the next class discuss and critique the event.

- College Republican hosts should use cameras with flashbulbs to dramatize the speaker’s arrival and departure.

- Hosts should be on the lookout for hostile leftist attendees and strategically seat, or place, College Republicans throughout the venue to break up potential “knots of hecklers”—the placing should be in a diamond fashion so as to have sympathetic campus conservatives on both sides of the room, as well as in the front and back.

- Open the event with a blessing from a local minister and a recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance.

- Make the introduction as exciting as possible.

- Plan your questions for the conclusion and provide them in advance to the guest speaker.

- If other questions are allowed, make sure a facilitator selects questions from “friendly audience members to take the pressure off the speaker.”

These kinds of tactics might have prevented what happened to Wallace at Dartmouth—if prevention had been desired. But the spectacle of being, in today’s parlance, de-platformed or canceled, could also serve one’s purposes. There was no aspect of a speaker event that could not be manipulated to undermine academic purposes—to maximize political effect.

A key lesson in maximizing manipulation was to be in power as the host and sponsor. The sponsoring group selects the speaker and the topic, markets and stages the event, and controls the questions. The host can also implement the dozen or so tactics outlined above.

One purpose of this postscript is to convey a teaching point for campus leaders and workers. The main lesson to be learned from Shepherd’s work for today’s university administrators, or department chairs or institute directors, is to never cede total event control to a campus student political group. You can allow for free expression, via the invitation, without ceding every point of choreography outlined above. Administrators can lessen the the spectacle of deplatforming on campus by preventing the manipulation of their institution.

——————————————————–

If you have been following this series since the start, thank you. My goals were manifold: convey the relevant stories and lessons from Shepherd’s book, explore the book more thoroughly for my own sake, understand the longer conservative effort in higher education (and how it seems to have begun in Shepherd’s period of study), and, finally, to promote Resistance from the Right to new potential readers. I did not mean for this series to expand into nine posts; in the beginning I thought it would be 4-5 total. But here we are—at around 9400 words total over the series. Anyway, buy the book! Or at least encourage your local libraries to own it. ? – TL

0