Editor's Note

This is part 8 in my series on Lauren Lassabe Shepherd’s Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & the Campus Wars in Modern America. You can find past posts at this link.

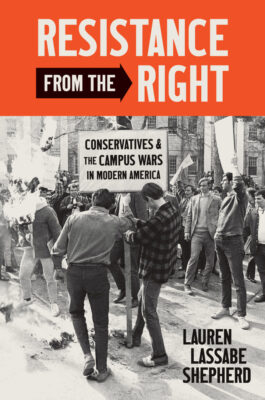

This is the cover of Shepherd’s *Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & Campus Wars in Modern America*. It shows male students protesting against Students for a Democratic Society by burning an SDS effigy at Harvard in 1969.

I can understand why some readers and academic reviewers might fear an overabundance of presentism in Resistance from the Right. Too many books—even academic ones—covering politics and political history have framed their studies in relation to recent history. Whether it is the Trump presidency, right-wing media, the Tea Party, terrorism, libertarianism, immigration woes, or the culture wars, the present and present-day concerns acts as a centripetal force in much of our political understanding. Shepherd does cover the Trump administration and Trumpism in her conclusion, but it does not in any way permeate the rest of the book. Despite her restraint, the polarization of the present moment pulls on all of our thinking, distorting the ability to obtain the perspective of distance.

This problem of presentism can certainly exist in professional histories of education, whether we consider K-12 or higher education. Education is a forever theme in the history of our culture wars, especially in our cultural-political disputes. So long as we have had public schools and universities, the public has been legitimately concerned with what is happening in them—meaning their faculty, their student experiences, their curricula, and their staff and leadership.

Conservative presidential administrations since Nixon have made all levels of education a focus of campaign rhetoric. In this series, Shepherd chronicled the ire of conservatives and the Nixon administration against left-wing campus “radicals” who opposed free speech limitations, the draft, and the Vietnam War. Beyond that, conservatives (with many liberals) have spoken out against busing as a legal remedy for discrimination. The 1970s saw concerns for religious schools. Sex education has been a concern since, well, the topic was invented as a potential curricular item. A popular theme of conservative politicians in the 1980s was a manufactured concern for the decline of public schools, exhibited in the famous “Nation at Risk” report. This continued with moderate Democrats and Republicans in the 1990s and 2000s with concerns about standardized testing scores and school “accountability.” The Bush 43 administration sought reform via the “No Child Left Behind” act of 2002. Then there was “Race to the Top” from the Obama administration in 2009.

The sum total of these efforts, over time, has been to made education feel like more of a political-rhetorical football (albeit with real monetary and on-the-ground effects) than a legitimate concern with the ground-level actions involved in teaching and learning. These efforts have also contributed to the difficulty for present-day readers to think objectively and historically—with critical distance—about the history of education. I believe this situation has also affected the ability of academic reviewers to assess new works on the history of education. Some want to see more connection to the present, as a show of relevance and to help explain today’s issues, even while others decry presentism.

I offer this meditation on presentism and the history of education to make the point that, while Shepherd’s study has obvious lessons for the present, as evident in my series of S-USIH reflections, she deeply contextualizes all of her topics in Resistance from the Right. Every chapter lives in its times with its actors and institutions. I cannot remember another study I have read that offers so much contextualization in the context of such a tight chronological period (1965-1970). Again, Shepherd was consciously restrained in the main body of her text given her period of writing and the numerous real connections to present-day conservative activities in, and attention to, the realm of higher education. Those connections are too obvious for the reader to ignore, but they do not necessarily implicate Shepherd in importing present-day concerns, norms, or moral issues into study.

In reviewing a book, one must be careful not only about reviewer assumptions (i.e., presentism), but also to distinguish between the reviewer’s wishes and legitimate points of critique. I have just a few of the latter—perhaps only two or three—and more of the former. In fact, most of the latter have to do with the fact that Shepherd’s study was generative of thought. It is provocative. Reading her work raises questions that will need exploring in future works by others (or Shepherd, if she wishes!).

By way of critique, I believe that there should be means for the reader to find and compare all of institutions considered in the book. This could be in the form of an appendix, or perhaps a more thorough index. I lean toward both, but definitely an appendix. Whatever the form, an academic user—a person who hopes to build on Shepherd’s work—should be given the opportunity to see Shepherd’s thoroughness in demonstrating that the work of YAF and campus conservatives was nation-wide. Despite the well-known fetish of higher ed commentators to focus on “the Ivies” (whether private or public), Resistance from the Right goes coast-to-coast, north and south. If student conservatives were not exactly popular on campus, they were a known entity. Some of their points found traction at various institutions. Also, higher ed junkies like me want to know if, and when, their alma maters were the subject of YAF activism!

I do realize that decisions about appendices and indices are not always fully controlled by first-time authors. Presses make decisions for them that sometimes feel absolute. It is possible, then, that Shepherd wanted more than what is here in terms of reader aids. Whatever the case, that particular aid would be really useful.

As something between a critique and a desire, I wished that gender roles and women might have been addressed even more prominently, and in a concentrated fashion, in Resistance from the Right. Most of Shepherd’s historically prominent actors in YAF were not surprisingly male. Even so, she did interview some YAF women and addressed their roles, and non-roles, in her text. I loved hearing, for instance, from Elizabeth Knowlton, Patricia Thackston-Ganner, and Judith Thorburn. Thorburn and Thackston-Ganner were contacted and answered questions (p. 24-25). A deeper exploration would be useful, however, because women’s rights were an important part of 1960s cultural activism. Bringing out nuance in a concentrated, prominent way might help explain how conservatism had to look in other directions as the 1970s progressed—helping add details to the bridge, using late-1960s college-educated politically-observant conservative women, between Michelle Nickerson’s 1950s Mothers of Conservatism and then what appeared in the conservative, anti-ERA movement around Phyllis Schlafly.

The contextual place of college-aged conservative women is explicitly addressed in Shepherd’s first chapter (pages 24-26)—which is where the abovementioned historical names arose. In that section Shepherd briefly and concisely covers gender demographics in higher ed, expectations for women in college, roles for women in all of the movements of the era, conservative women’s views on feminism and women’s rights, sexism in conservative groups, safety, dress codes, and gendered patriotism. Other women arise in Shepherd’s text (e.g., Anne Edwards, Colleen Conway McAndrews, Gayle Faunce, Priscilla Buckley, Anna Chennault, Alida Milliken), but they feel submerged in relation to the prominent male actors (few of the women I just named appear by name in the index). This submersion is of course not an accident in relation to the sexism of the times in YAF and generally. The broader story of college-aged conservative women in the late 1960s, however, might tell us more about the persistence, or occasional power and resonance, of campus conservatism then and later.

The topic of conservative campus women left me with questions: What of archival materials at women’s colleges or HBCUs that might address conservative women, either as students (individually or in recognized groups), staff, or faculty? What of oral histories about campus conservatism from the general run of women (the 48 percent, per page 24) who attended college in the late 1960s? Shepherd explored a number of newspapers and campus periodicals. Did conservative or moderate women write newspaper or magazine advice columnists (i.e., Ann Landers) about larger political issues in late 1960s? Or maybe there are scholarly articles from the period, from other disciplines, that covered the voices and activities of conservative women in higher education? Or what of survey results (Gallup, census, sociological) about college-aged women’s political views? Perhaps my questions are another book or study entirely. But I did wish for more prominent and explicit treatment, perhaps in a single focused chapter, of black and white conservative women during all phases of this study.

In what is definitely a mere wish—one, again, generated by Shepherd’s good work—I wanted a few concentrated institutional cases beyond Columbia University. I wanted to know more about the activities of YAF members and campus conservatives at, say, a southern institution, such as the University of South Carolina or Mississippi, in the 1965-1970 period. That kind of deep institutional focus affords opportunities to draw out important university actors, such as student parents, Greek system members, alumni, staff, leadership, a range of faculty members, and local community and business leaders. An attempt at a focused, integrated case story might reveal more about the flows of power, funding, and student-elder interactions. Perhaps someone else, inspired by Resistance from the Right, can do perform that deeper dive.

That’s it. I hope what I have relayed here in no way overshadows my admiration for Shepherd’s work. Given the way that politics affects on-campus happenings, for and with students, I believe every single higher education institution with a functioning library should own a copy of this book. Faculty and administrators should study it to learn about politically-motivated organizations, using or working with students, can influence all aspects of campus life. By understanding these flows of influence, universities can work better to maintain their independence. The integrity of higher education depends it.

Tune in next week for one last post on Shepherd’s book—a postscript on the spectacle of cancel culture and “deplatforming.” – TL

0