Editor's Note

This is part 3 in my series on Lauren Lassabe Shepherd’s Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & the Campus Wars in Modern America. You can find parts 1-2 here and here.

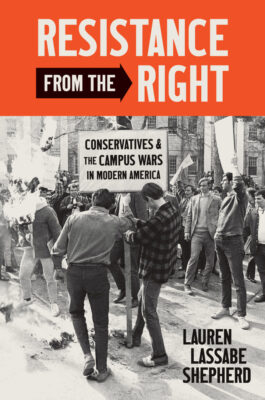

This is the cover of Shepherd’s *Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & Campus Wars in Modern America*. It shows male students protesting against Students for a Democratic Society, by burning an SDS effigy, at Harvard in 1969.

Members of Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) did not stop with creating “innocuous” auxiliaries and front groups to help forward their anti-leftist cause. Working from a base message that heavily emphasized anticommunism, many other practical tactics and strategies were employed on college campuses. Lauren Lassabe Shepherd outlines most all of these efforts in Resistance from the Right.

In addition to the creation of innocent-seeming front clubs, they also formed study groups. These YAF-backed groups sought to mix a few of their own members with regular students. They would read and discuss texts in order to promote anticommunist agenda. Through these groups they might draw in allies, make converts, and perhaps obtain longer-term adherents (p. 62). The groups presented the chance to promote opportunistic friendships and fellow-feeling.

The study groups and new auxiliary groups were encouraged, when possible, to form partnerships with other student campus entities and outside organizations. Shepherd outlines that these included “the US Junior Chamber of Commerce, the Young Republicans, …local business or civic clubs,” ROTC members, and even Young Democrats “when possible” (p. 62). Partnerships helped foster the illusion of a larger front—of something big if also quieter than the New Left.

When YAF’s new campus committees were organized with their partners, they set shared objectives, set up advisory boards, and, most importantly, touched base with “press outlets to ensure that, like the Left, their activities made headlines” (p. 62).

Because Shepherd is not concurrently narrating the work of the campus left, we do not know how much YAF tactical work either mimicked their opponents or was novel to them. That point matters less than the fact that a conservative campus counter-establishment arose in the late 1960s.

Meanwhile, these new auxiliary groups and committees included “state legislators as advisory board members” (p. 62). In turn, group members would draft “anticommunist bills” for local legislators, hoping to have them proposed in legislative sessions. They carefully chose, when possible, “ ‘moderate’ lawmakers to introduce the bills.” If this worked, the YAF or partner students would “assume the responsibility for doing all the work on behalf of the sympathetic legislator” (p. 63). In sum, they became local lobbyists and volunteers for politicians.

Much of the intimate knowledge about this, for Shepherd, came from a strategy document authored by Randal C. Teague that was published in New Guard in December 1967 (p. 212n47). Teague served as a YAF board member, and was also the YAF’s executive director at one point. Shepherd had introduced Teague earlier in the text, having also interviewed him in June of 2018 (39, p. 208n18).

In that prior section Shepherd outlined how Teague believed that “YAF members had the right gut instincts” but lacked the necessary “intellectual underpinnings” to discuss and promote their politics (p. 39). This was especially true in campus settings where they were only being introduced to works and ideas from their liberal, or even radical, professors. The remedy was book sales. The Volker Fund provided conservative books (i.e., the right great books) with the right ideas (i.e., traditional morals) to YAF chapters, as well as to College Republicans and Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) chapters. The Volker Fund also donated books to college libraries.

To summarize: Study groups. Auxiliary groups. Advisory boards, Partnerships. Lobbying at the state level. Practice bill writing. Book donations. Intellectual strategies to counter perceived liberal professors. Support from deep-pocketed donors.

While I was aware of the existence of YAF, ISI, College Republicans, the Volker Fund, and other conservative elements in higher education due my prior reading on the history of conservatism, I was entirely unaware of the sophistication in place by the late 1960s. Reading Shepherd’s book was my first encounter with the complexity of their operations, as well as the interrelatedness of these entities. I feel I should have known about these tactics, strategies, and the work done, but here I am. I am grateful for the publication of Resistance from the Right.

Next week: On the weaponization of humor in campus politics. – TL

0