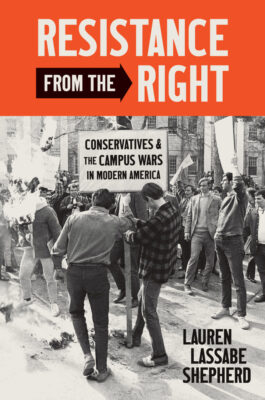

This is the cover of Shepherd’s *Resistance from the Right: Conservatives & Campus Wars in Modern America*. It shows male students protesting against Students for a Democratic Society, by burning an SDS effigy, at Harvard in 1969.

One of the more difficult things for faculty, staff, and leadership to deal with in higher education is idea that their cherished place of work is also a site for information wars. Many professors—especially in the STEM fields and professional schools, but also in some social sciences—want to imagine that they can teach their content, ideas, and thought processes at some remove from society. Courtesy of more regular student conversations and demands, student affairs staff are generally more aware of those outside forces impacting learners. Even so, staff members cannot always see how those forces are directly impacting the classroom or student groups. Many students, too, want to imagine that what they are doing in school can be compartmentalized from others areas of their life. None of these parties, whether busy students, aloof administrators, and myopic faculty, spend much time thinking about how outside actors might be impacting their distinct experiences. It takes work for all of these parties to connect the dots.

Lauren Lassabe Shepherd’s Resistance from the Right helps the reader make these connections. It deconstructs our various blind spots, or points of naivete. The book helps those of us in higher ed to expand our imaginations to include some unsavory, or unfortunate, facts. It outlines various tactics employed by those who use our institutions as just one more place to fight their political, social, and cultural battles. Reading Shepherd’s book brings an element of realism to one’s situation. It deeply troubles our personal, and social, myth of the “ivory tower.” Resistance from the Right helps us see that some of our institutions have foundations that rest on clay rather than bedrock.

There are many places in Shepherd’s book where one could reflect on the notion of information wars on campus. I recall being particularly struck by that idea around pages 61-63. In this portion of the narrative of chapter three Shepherd is reflecting on how YAF (Young Americans for Freedom, whose 1960 creation is covered in chapter one) focused on communism as the “issue ripe for exploitation” (p. 61). Earlier they had already, in the Sharon Statement of 1960, “branded communism ‘the single greatest threat’ to liberty” and had argued that the United States “should stress victory over, rather than coexistence with, this menace.” Members of YAF, moreover, were convinced this was “an urgent matter of human rights” due to estimated deaths of innocents “in Russia, China, Cuba, and elsewhere” (p. 61). They believed—and Shepherd articulates this well—“that communism was not an ideological abstraction but an imminent threat on a global scale—one infiltrating their very campuses through radical peaceniks and civil rights agitators” (p. 61).

This historical motivation for Young Americans for Freedom was, in fact, sincere. It carried an emotional valence. Members of YAF had a deeply felt conviction that certain campus actors exposed the nation to risk. Their sincerity and conviction gave them power. Think about how, in your life, encounters with sincere believers impact you. Whatever topic is presented, if the conversation partner is sincere and they have some facts on their side, they leave you with questions and doubts. They diminish, temporarily at least, your own energy for your oppositional cause. The fact that the information they provided is tied to larger ideas strengthens their case. In this historical situation presented by Shepherd, fears of communism—the beating heart of the anticommunist ideology—had been in the air since the 1920s. The YAF cause had a 40-plus year track record of concern by the late 1960s. Two hot wars had been fought, with the second still in progress, to fight the perceived communist menace. It made sense to YAF and to many off-campus to fight an information war in higher ed to return young people to a proper respect for the enemy.

Conservative actors on campus, whether students or outside influencers, but on this long-held fear. They could use it to build up their ranks on campus, creating a pipeline for larger societal and political conservative movement. Members of YAF could help by organizing “against ‘the left’” (p. 62). This mean focus on the anti-Vietnam War movement to tap into communist fears, while conflating that with the civil rights and Black Power movements, as well as radical feminists and libertines (p. 62). By utilizing real and familiar fears, these 1960s conservatives could, perhaps, build a movement.

By 1968, YAF had already been around for 7-8 years. Shepherd notes that their brand had already obtained an association with extremism. To combat this, they sought partners. In a coalition with newer student organizations they could disguise their own positions and interests. When YAF could not find partners, they made their own. Shepherd notes that they created “auxiliaries with ‘innocuous’ names, such as the National Student Committee on Cold War Education or the Pennsylvania Committee for Improved Schools and Education” (p. 62).

Beware then, today, of “new” student groups. Perhaps a new entry in various campus conversations is just an old group with a new front. Look for people connections to older entities with more established resources. Perhaps a new domestic or campus crisis really does create a novel group or coalition. It is true that students form ephemeral entities, and that new campus factions are formed. It does not hurt, however, to be wary of old ideologies and campus actors who are not letting a crisis go to waste. Information wars sometimes require the disguise of sources. This prevents reflexive dismissals and categorizations.

Next week: More tactics and strategies in campus politicking and student information wars. – TL

0