The Book

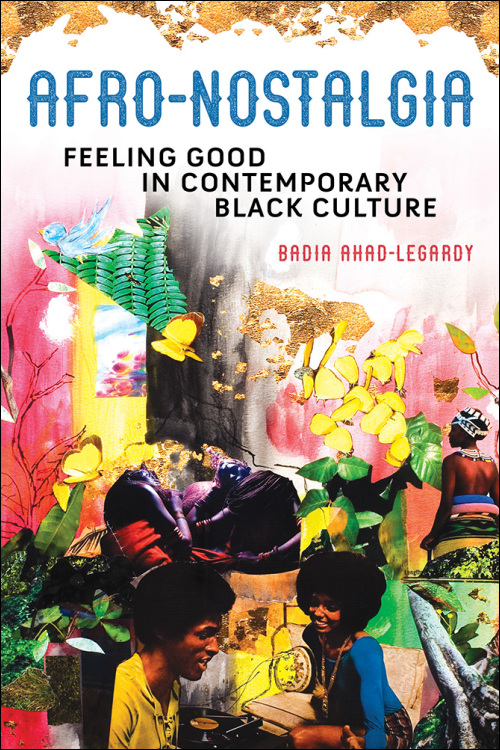

Afro-Nostalgia: Feeling Good in Contemporary Black Culture

The Author(s)

Badia Ahad-Legardy

How can one be nostalgic about a traumatic past? That’s a key concern in Badia Ahad-Legardy’s book Afro-Nostalgia: Feeling Good in Contemporary Black Culture. She points out that the study of nostalgia generally leaves out the relationship between blackness and nostalgia: “historical nostalgia, with respect to African American memory, is rarely (if ever) invoked, precisely because narrative of black subjugation and disenfranchisement do not easily mesh with the romantic wistfulness generally associated with nostalgia” (p. 1). In other words, “the ‘past,’ for many African-descended people, does not bring with it sentiments of good feelings” (p. 159).

When I was preparing this review, I watched Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s Oscar winning documentary Summer of Soul, a remarkable film about the 1969 Harlem Summer Festival, a series of concerts celebrating Black pride, attended by hundreds of thousands of people. The film asks why these concerts – and the stunning footage captured by filmmaker Hal Tuchin – had largely, and inexplicably, been forgotten. One particularly memorable scene shows singers Billy Davis, Jr. and Marilyn McCoo watching themselves perform at the concert with their group The 5th Dimension. They’ve never seen the footage, and as they watch themselves performing decades ago, they are overcome with emotion – loss, nostalgia, pride, and sorrow. And, perhaps, anger in realizing that the film, and the Harlem Summer Festival, had been almost lost to history. Despite taking place in Harlem, the Summer Festival was eclipsed by Woodstock – which happened that same summer, mostly ignored by music critics and historians, and thwarted by film producers and studios, arguably due to racist ideas about its importance and potential market. Questlove’s revelatory restoration and reclamation project offers a powerful example of afro-nostalgia’s potential.

Drawing from a diverse array of sources, including academic research, literature, film, and popular culture, Ahad-Legardy traces “the risks of nostalgic remembrance” that often obscures trauma. By turning to cultural production and pleasure to explore nostalgia, she joins a productive list of recent scholarship that (re) examines African and Black cultural imagery in light of contemporary concerns of representational ethics.[i] She calls upon African American artists and writers “who materialize nostalgic pasts that unmoor, through imaginative invention, the traumatic roots of the black historical past” (p. 87). She points to “nostalgia’s power to shape and wield politically and socially conservative forces” (p. 19). She contrasts her conception of afro-nostalgia with black conservative or Jim Crow nostalgia. Such nostalgia “is often evoked as an expression of one’s discontent with the present, and the recollection of a more glorious past – whether real or imagined – is seen as a respite from the ills of the current moment” (p. 159).

Afro-nostalgia, in her view, focuses “on the evocation of individual and communal acts of affective pleasure” (p. 19). For example, she proposes that comedian Dave Chappelle’s 2004 block party, held in Brooklyn and featured in his 2005 film Block Party, “is an attempt to reclaim a sense of communal solidarity and identification” (p. 19). Chappelle recalls the 1972 Wattstax concert, featuring primarily African-American musicians from Stax Records, another legendary music festival that has been much less widely celebrated than, for example, the 1968 Monterey International Pop Festival or the 1969 Altamont festival.

Through careful analysis of how nostalgia is conceptualized and invoked, often by conservative voices, she develops a counter concept of afro-nostalgia, “to consider nostalgia as a relevant and meaningful concept in constructing new narratives of black life that resist, complicate, and complement dominant traumatic framing” (p. 159). She argues that “the relationship between nostalgia and trauma is not a binary one; they are, instead, conceptual cousins” (p. 7). Here Ahad-Legardy invokes cultural theorist Ann Cvetkovich’s notion of “public cultures of memory,” to argue that it’s possible for traumatic pasts to be “refigured as transformative sites of healing” (p. 7).

Ahad-Legardy provides an alliterative map for recuperating nostalgia through four paths: retribution, restoration, regeneration, and reclamation. In chapters devoted to each, she invokes Black cultural and literary examples as illustrative instances and for conceptual development. For example, she saw joy and unabated black bliss in artist Kerry James Marshall’s 2003 Vignette that depicts two silhouetted figures running outside amidst flying birds. Yet, her students responses to the painting “were all about slavery” (p. 85.) These contemporary students viewed the painting “the mere fact of their blackness was enough to intimate that this scene was implicated in a larger narrative of subjugation.” (p. 85). She introduces the chapter on regeneration with this example to underscore how oppression informs Black lives, but at the same time, to work through a reimagining of black origins in more positive, nostalgic terms.

In a powerful section, she reflects on obtaining genetic information from an AncestryDNA analysis kit. She invokes her maternal great-great grandmother, Catherine Lowe, nicknamed “Red” for her assumed Choctaw heritage. But the DNA results flatly deny any Native American markers. As she wonders whether her family invented a different ancestral lineage, she draws upon the notion of a “re-fabled self,” to show how regeneration often implies “the (re)formation of something new after a loss or injury” (p. 87). In the chapter on reclamation, she offers an engaging discussion of foodways, as she links eating preferences, religious food strictures, and family stories. She illuminates food as an evocative nostalgic trope, “how the positive emotions associated with food nostalgia are entangled with broader political and racial nostalgic desires, and how contemporary black chefs, in particular, navigate this shifting terrain” (p. 118).

In this way, her work on afro-nostalgia taps in to wider cultural, personal, and political concerns. Many of us find ourselves rethinking nostalgic feelings about the food we grew up with, our family histories, and the “history” we were taught – or not taught – in school. She offers an insightful and instructive way to think about nostalgia with insight, encouraging a reflective engagement with nostalgia as a productive act, not merely a reactionary response to contemporary reevaluation of historical events. She concludes: “I read afro-nostalgia as an opening to consider other important and understudied sentiments produced by and through the afterlife of slavery, particularly those emotions, feelings, and memories from which black folks are considered ‘immune’” (p. 165.)

[i] See, for example, Mark Sealy, Steven Evans, and Max Fields, eds., African Cosmologies: Photography, Time and the Other (Amsterdam: Schilt/Houston: Fotofest, 2020), Lyneise E. Williams, Latin Blackness in Parisian Visual Culture, 1852-1932 (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), Rebecca Peabody, Steven Nelson, and Dominic Thomas, eds., Visualizing Empire: Africa, Europe, and the Politics of Representation (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2021), and Kristina Wilson, Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body: Race, Gender, and the Politics of Power in Design (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021).

About the Reviewer

Jonathan Schroeder is the William A. Kern Professor in the School of Communication at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. His publications include Visual Consumption (Routledge, 2002), Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America (MIT Press, 2017; co-author), and Designed for Dancing: How Midcentury Records Taught America to Dance (MIT Press, 2021; co-author). He is a board member of the Race in the Marketplace Forum and a member of the Diversity Scholars Network, University of Michigan.

0