Editor's Note

August 11, 2023, marks the 50th anniversary of hip-hop’s origins. S-USIH invites contributions on hip-hop’s intellectual history across its decades to celebrate this anniversary. The following post is from current S-USIH blog editor Katherine Rye Jewell, drawn from her research on the history of college radio.

Hip-hop and college radio have a complicated but connected history. Some stories are well-known, such as how members of Public Enemy found one another and their love for music and expression at Adelphi University’s WBAU on Long Island. KCMU at the University of Washington and WKCR at Columbia University and WHPK at the University of Chicago featured groundbreaking hip-hop shows that cultivated artists and fans alike, including Sir Mix-A-Lot, Nas, and Common, among many others. Few hip-hop radio DJs have the track record of WKCR’s Stretch and Bobbito (Columbia University) for legendary musical contributions.

These stories of success punctuate what has often been a troubled relationship between Black musical expression and collegiate signals, in which students of color struggled to find programming that reflected their musical preferences or offered access to the airwaves. Yet other opportunities for cultural connection and dissemination exist – such as college radio’s jazz programming chronicled by AJ Johnson and other historians and musicologists. Regarding hip-hop, sociologist Anthony Kwame Harrison notes how college radio, particularly at predominantly white institutions, presented the possibility of creating “sonic belonging” for students often feeling outside of campus culture.[1]

The same can be said for communities surrounding these stations, and particularly for those that responded to DJs’ efforts to create a community mission. At these stations, even at predominantly white institutions, the relationship between hip-hop and college radio went beyond fostering musical creation a cross-over: it helped support, with media connections, the communities that were the foundations of hip-hop culture. Such potential for community cooperation, sonic connections, aural infrastructure to forge belonging and meaning point to the deeper significance of hip-hop to local and national culture while also highlighting hip-hop’s roots in soul and funk and the activist networks and organizations that sought to democratize and diversify institutional cultures. Such projects persisted despite universities’ often-damaging projects in urban renewal and gentrification and failure to meaningfully incorporate Black students into campus cultures.[2] House parties and community celebrations nurtured hip-hop’s emergence as an art form, with its politics and expression grounded in the experience of urban residents in the early 1970s, with art and music frequently only found on college or community signals across the nation. Yet as the landscape of Boston’s college radio demonstrates, those private spaces nonetheless became a part of the city’s ecosystem, revealing the city party infrastructure and connections to media that would be instrumental in hip-hop’s rise.

Image: WMBR studio door in the Walker Memorial building, pasted into “The Book” in WMBR studio, Vol. AB.

In Boston, soul music fans could turn to college stations after 1969. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the campus Black Student Union chapter enjoyed a fruitful connection with the campus radio station, WTBS (later WMBR). Boston Globe columnist John Robinson described the “aridity of the AM airwaves insofar as consistent soul programming is concerned.” He encouraged readers “to expose the assault of insipid broadcasting” by tuning in to student-run programming. Although Boston University used a “funding crisis” to drop its soul program, The Drum, Harvard, Boston College, Emerson, MIT, and Tufts all offered a range of “black-oriented” programs. Harvard consistently programmed jazz since the 1950s, while Emerson offered The Black Experience. Northeastern also offered Soul’s Place, dedicated specifically to the genre.

Yet Robinson singled out The Ghetto at MIT for its quality and time dedicated. In addition to the “Memphis Sound” program and a throwback R&B show on weekends, MIT’s station kept hungry listeners sustained with music of a quality “which is very high indeed.” Although most of these stations had only low-power FM signals. WTBS’s eight watts when The Ghetto debuted increased to 720 by 1972, helped along by an MIT Trustee and FCC member who helped smooth the process. But as with other stations still offered only a limited range. But the future of radio targeting black residents seemed bright, in Robinson’s view. Even with this limited coverage, the signal reached densely populated areas. As the first engineer for The Ghetto, W. Ahmad Salih remembered, the number of shows and nightly programming meant MIT’s station became “the number-one Black radio in the entire Boston metropolitan area.” MIT’s offerings amounted to more than alternative musical entertainment. These shows collectively offered “a vehicle to sort of help in uniting the black community,” the former staffer explained. More than music, The Ghetto and the BSU offered local, national, and international news.[3]

With other college-radio offerings in the market, student DJs designed programs to emulate higher-power, black-oriented FM stations elsewhere, succeeding in diversifying the sound of The Hub’s airwaves. As Salih remembered, “We became like the No. 1 station in Boston—I mean black, white, everything.” WTBS featured visiting artists to promote local appearances and reach fans. Pop entertainers such as the Jackson Five and jazz artists such as Al Jarreau visited WTBS to record promos and give interviews. Visitors included Aretha Franklin, Richard Pryor, Issac Hayes, and Stevie Wonder because, as Salih put it, “if you had any event that was going on in Boston that was black, then you had to get it on ‘The Ghetto’ because everyone would hear it.”[4] In 1972, The Ghetto hosted a concert by War that attracted more than 20,000 fans.

Inspired by these connections, Ghetto staffers imagined a “City Party,” with the “hub” at the Walker Memorial building, where the radio station broadcast. The Ghetto would broadcast music from the party, with “satellite parties” at other area colleges, who rebroadcast the program. Then, as Salih described, “everybody in their homes and cars were urged to turn on The Ghetto—and to play it loud!” Remote DJs would “check in” to the central broadcast and keep the party going. Salih remembered, “You could stand outside almost anywhere in the Boston metro area and hear the party. People were dancin’ in the streets!” The event netted the station more than $10,000 in proceeds.[5] Student staffers for The Ghetto found side-gigs as warm-up acts or emcees for concerts, given their notoriety.[6]

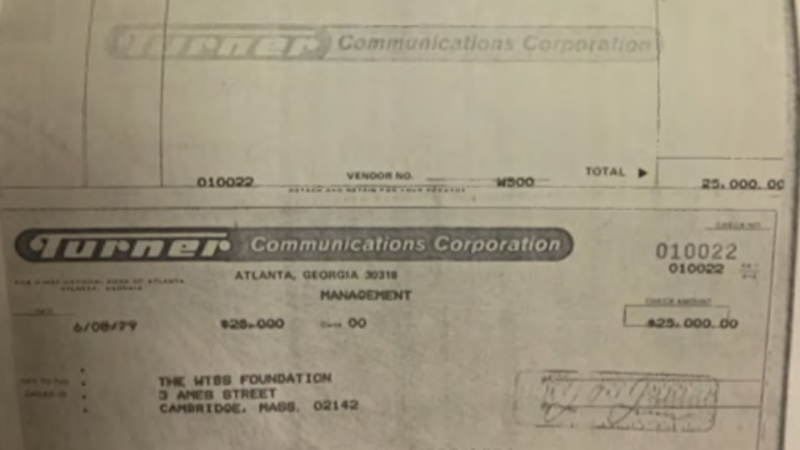

Ted Turner’s check compensating WTBS for releasing its call letters, thus becoming WMBR, April 8, 1979. “The Book,” WMBR Studio, Vol. X.

The Ghetto’s staffers became key leaders at the station. Unlike other institutions, where Black students found campus stations similarly closed to black students, MIT proved different. James Clark, a DJ for The Ghetto, became WTBS’s General Manager in 1971, and Salih became the station’s first licensed engineer along with serving as comptroller.[7] MIT’s station continued to offer significant time to programs targeting the area’s Black residents with music and news tailored to their interests. Eventually, commercial FM stations in the market emerged to displace MIT’s status as Boston’s leader in Black music, but it remained an important spot on the dial for soul, R&B, and reggae, featuring both student and community DJs.

MIT’s unusual governance structure allowed WMBR the freedom to work with local communities and area radio stations to promote these events, and which also facilitated a famous event at the station in the 1970s: the change in its call letters from WTBS to WMBR when Ted Turner effectively purchased them in 1979. WTBS’s independence from MIT, a divergent governance structure, revealed the variety of student-run stations and their oversight, in addition to formatting. Although the station received generous assistance with on-campus space and qualified as a student activity, it enjoyed greater independence than other college stations, which fostered its community radio culture. Like other college stations across the nation, when DJ Kool Herc’s party turntablism spread and sparked artistic innovation, WTBS’s college and community DJs were there to pick up on the sounds.

Despite existing in an ecosystem somewhat apart from commercial FM and AM radio, or even from host institutions, NCE-licensed stations still worked within the broader structure of broadcasting. MIT’s station learned the opportunities and challenges of this relationship. Balancing the demands of student-run radio as a student activity often strained a station’s community functions, with rifts existing between student DJs (who remained in many cases overwhelmingly white) and community DJs. Where beneficial relationships still existed, Black students on campus still often struggled in their desire to seek college radio to construct “sonic belonging” in the 1990s. College radio’s reputation for launching white indie-rock artists, and nurturing a genre of “college rock,” tends to overshadow the medium’s longstanding and parallel relationships with hip-hop.

Nonetheless, mining the links between college radio and hip-hop reveals how the emerging genre shaped and constituted new conceptions and reflections of community, town-and-gown relationships, and the role of higher education – though fraught – in cultural development. Indeed, college radio’s connections to the experiences and contexts that shaped hip-hop’s artistic and political evolution reveal its deeper meaning and significance to U.S. cultural and political history.

Katherine Rye Jewell is professor of history at Fitchburg State University and the author of Live from the Underground: A History of College Radio, from University of North Carolina Press (December 2023).

[1] Anthony Kwame Harrison, “Black College-Radio on Predominantly White Campuses: A ‘Hip-Hop Era’ Student-Authored Inclusion Initiative,” Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies 9, no. 8 (2016): 135–54; Aaron J. Johnson, “Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University, 2014). MC and hip-hop scholar Akua Naru has also presented work on the relationship between hip-hop and college radio.

[2] Davarian L. Baldwin, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities (New York, NY: Bold Type Books, 2021).

[3] John Robinson, “Black-oriented FM…sounds of the soul,” Boston Globe, March 20, 1973. BAMIT, “Reflections of an MIT Student Activist,” Medium, July 31, 2017, https://medium.com/bamit-review/reflections-of-an-mit-student-activist-d2035740e2ff. Accessed February 11, 2019.

[4] W. Ahmed Salih in Clarence G. Williams, Technology and the Dream: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT, 1941-1999, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 380–381.

[5] “Reflections of an MIT Student Activist.”

[6] Salih in Williams, Technology and the Dream.

[7] “Reflections of an MIT Student Activist.”

0