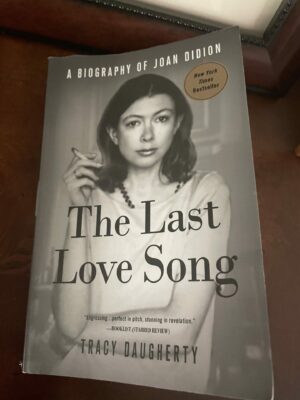

Over the past couple of months I’ve been spending a lot of time with Joan Didion. In addition to re-reading her collected nonfiction, I made my way through Tracy Daugherty’s biography, The Last Love Song (St. Martin’s, 2015). Didion’s writing is a love song to a vanished California that never was, an imagined paradise lost to Okies and aerospace engineers. Daugherty’s biography is, I suppose, a love song to Didion’s voice. But it stands also as an homage to another lost paradise.

In his preface to the book, Daugherty writes, “Above all, in studying Didion, I am fashioning literary biography as cultural history as well as an individual’s story. I take my cue from her long and varied career. Her life illuminates her era, and vice versa. If this were not so, a biography of Joan Didion would serve only prurience. Writing is the record we have of our time. Just as certain memories burn brighter with age…so, too, do the pages of our contemporaries, the marks they have made of our lives, cast us more vividly as immediate circumstances vanish and the record’s uniqueness comes more to the fore.”

In his preface to the book, Daugherty writes, “Above all, in studying Didion, I am fashioning literary biography as cultural history as well as an individual’s story. I take my cue from her long and varied career. Her life illuminates her era, and vice versa. If this were not so, a biography of Joan Didion would serve only prurience. Writing is the record we have of our time. Just as certain memories burn brighter with age…so, too, do the pages of our contemporaries, the marks they have made of our lives, cast us more vividly as immediate circumstances vanish and the record’s uniqueness comes more to the fore.”

Daugherty’s language—pages, marks—gestures toward the stolid materiality of “the record” where Joan Didion is concerned. Daugherty’s book is filled with descriptions of those actual marks on pages, of notes penciled on the backs of photos, of single index cards and bound galleys, of clipped yellowed newsprint columns and itemized expense reports, of multi-page layouts in print magazines. Those once ubiquitous media of “our time” are themselves among those vanishing “circumstances” that make Joan Didion’s perspective unique.

What emerges from Daugherty’s book is not just a story of the life of Joan Didion but a story of the world of print, the world of magazine publishing, during the Cold War. It’s the story of how a young couple of writers, Didion and her husband John Gregory Dunne, could manage a comfortable shabby chic life on the proceeds of regular columns for The Saturday Evening Post, reporting assignments for LIFE, and the occasional script treatment.

It’s not the Hollywood writing that dazzles, but the magazine work—the work, and the pay. Joan Didion made her living and her mark as a magazine writer. The essay collections were pulled together from magazine columns and features. Some of her most lyrical prose about California—“Holy Water,” for example—ran first as copy for her column in The Saturday Evening Post. Not The Paris Review, not The American Scholar, but the mass circulation general interest magazine my grandparents took. “Slouching Toward Bethlehem” ran with a photo spread in LIFE.

I knew all this already about Didion; we know all this about Didion and the other practitioners of “the New Journalism.” This is why we call them new journalists, after all: they wrote for “the magazines,” magazines with huge readerships, magazines that paid well. That is the vanished world captured so beautifully, if incidentally, in Daugherty’s biography of Didion, at once much more real yet just as unrecoverable as California before all the “new people” arrived to upend paradise.

0