The Book

Black Empire, Beyond Coloniality, George Padmore’s Black Internationalism

The Author(s)

Michelle Ann Stephens, Aaron Kamugisha, Rodney Worrell

In what is arguably the most thorough study of US race relations before World War II, Swedish economist, Gunnar Myrdal, argued that despite the brutal legacy of slavery and Jim Crow racism, American blacks rejected extremism. Neither Fascism nor Communism attracted them. American communists, however, mandated by Lenin, made repeated efforts to recruit them promising to deal humanely with “The Negro Question.”[1] To the extent that membership did grow in the 1920s and 1930s it was due to the efforts of the Communist International (COMINTERN) and a cadre of Caribbean intellectuals skilled in journalism and Marxist agitation.[2] These Intellectuals are the subjects of these three substantial academic books.

Although in print since 2005, Michelle Ann Stephen’s book was prescient in describing “how certain black leaders and intellectuals of Caribbean descent chose to imagine African Americans as part of a global political community …” (1). Following a “gendered approach,” she delves insightfully into how exclusively male intellectuals from the Anglophone Caribbean attempted to imagine a transnational form of black nationality that “could both transcend nationalism and reimagine the state itself,” a radicalized approach to “The Negro Question” (4). While she chose to focus on Marcus Garvey, Claude McKay and C.L.R. James – it is James who most represented the new interest in the role of black communists, black radicalism and Pan-Africanism. He was, according to Cedric Robinson, most representative of “The Black Radical Tradition.”[3] Without breaking any new ground on James’ well-known trajectory, Stephens spends a good portion of her book describing what she calls James’ “masculine” courage and fortitude (204-240). She compares it with the behavior of Toussaint L’Ouverture in the Haitian Revolution, which she calls the founding narrative in black transnational discourse, “an exalted romance of the race” (205). She chose James’ confrontation with the US immigration authorities as an example of his Toussaint-like courage. Unfortunately, there is more myth than reality in this story. Facing deportation as a Visa Overstay, James’ assertion that he would not “grovel in the dirt” by asking for bail or other forms of legal assistance (273) is portrayed as James’ heroic masculinity. In reality, James launched a large campaign, distributing a book written while at Ellis Island to every member of the US Congress and dozens of other authorities full of anti-communist claims and a claim Stephens does not mention. The book, James said, “is also a claim before the American people, the best claim I can put forward, that my desire to be a citizen is not a selfish nor a frivolous one.”[4] Beyond that, Stephens is quite correct in emphasizing James’ continued, life-long role in promoting the black revolutionary tradition of Trotskyism.

Aaron Kamugisha’s Beyond Coloniality: Citizenship and Freedom in the Caribbean Intellectual Tradition, represents the radical dimension of the black nationalist tradition. In the epigraph to Chapter 2, the author quotes from Karl Marx’s 1844 statement that intellectuals had to engage in “a ruthless criticism of

Aaron Kamugisha’s Beyond Coloniality: Citizenship and Freedom in the Caribbean Intellectual Tradition, represents the radical dimension of the black nationalist tradition. In the epigraph to Chapter 2, the author quotes from Karl Marx’s 1844 statement that intellectuals had to engage in “a ruthless criticism of

everything existing” including not being afraid of speaking out or of being in conflict with the powers that be. Kamugisha has taken Marx’ advice to heart. He starts with a categorical statement, never contradicted elsewhere, that the Caribbean “is in a state of tragedy and crisis, destroyed and corrupted by a post-colonial malaise wedded to neocolonialism.” He is adamant throughout that the cause of this dystopia is “global neoliberalism” which portends the coming of “a ruthless authoritarianism” brought on by a governing elite “genuflecting” before international capitalism(1).

After that, nothing escapes the author’s intellectual wrath. Caribbean nationalism? “Perfectly compatible with elite domination.” (p. 80). Multiculturalism? “Facilitates the reproduction of Western bourgeois ways.” The Neo-Liberal economics practiced in the region? “Middle-class genuflection to Western Capital.” (p. 54). Barbados – the most successful democracy in the region – a “tragedy” (205).

His harshest words, however, are reserved for those promoting a mixing of race, culture and language known as “creolization.” So, the spirited celebration of creolization by the Martinican “creolistes” Jean Bernabe, Patric Chamoiseau and Rafael Confiant is labeled “infamous” (85). Even Edouard Glissant’s “antillanité,” a much-admired, optimistic vision of a region where cultural and racial mixing is evident, is trashed. In this critique of the post-colonial Caribbean, Kamugisha leans heavily on James’ writings, despite his perplexing admission that his was not a full analysis of James but rather “a desire to use James to think concretely about the contemporary moment in the post-colonial world …” (p. 43). Alas, one would search in vain for a James as virulently against what the author calls the post-colonial “nightmare” presented here. Much more accurate are the reminiscences of his close friend, John Bracey:

What C.L.R. accomplished was to smooth over some of the rougher edges and to loosen up some of the more rigid dogmatism of the views of myself and other young black radicals.[5]

What could be the author’s alternative to the despised colonial mentality and status of the middle class? No existing society is mentioned. And, yet the author’s call on the “radical Caribbean intellectual” steeped in the “Black radical tradition” to claim that a radical alternative to the “coloniality of the contemporary moment, seems the only future worth imagining” (103). Finally, in calling for the “remaking” of the Caribbean, he recommends “love” and – in what has to be an astonishing ontological non sequitur – he cites Che Guevara as epitomizing that sentiment(214). At least Marcus Garvey and other “Back to Africa” promoters had a promised land, an utopia in mind. Kamugisha gives us none.

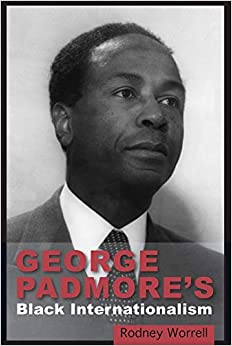

For the true man of action in the black nationalist tradition, one has to turn to Rodney Worrell’s study of George Padmore, code name of Malcolm Nurse from Trinidad. Worrell had to deal with the fact that James R. Hooker had written a well-reviewed book on Padmore seven decades ago.[6] He met that challenge very well indeed. Padmore was educated at Trinidad’s elite and fully integrated St. Mary’s College. He migrated to the US to attend the segregated Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. This experience and his many confrontations with the vile Jim Crow racism “heightened” his deep hatred of the system and resulted in radicalizing him (22). “Radicalization” led to his joining the US Communist Party, like so many other West Indian intellectuals, but few American blacks. Renowned for his writing and speaking skills, he was soon promoted to then become the first black member of the COMINTERM. Hooker had claimed that memories of Padmore’s life before his involvement in Africa were quickly forgotten and that his entire pre-1957 career was shelved by friends and enemies alike (140). It is the singularly good contribution of Worrell that he restores Padmore’s pre-1957 role. His emphasis on Padmore’s fundamental 1955 book, Pan-Africanism or Communism which reveals his deep hostility towards Soviet Communism, is well done. Padmore describes communist activities and policies towards blacks as opportunistic and hypocritical and blacks generally as revolutionary expendables.[7] That said, Worrell does not resolve the major mystery of Padmore’s “path from communism.” Was his later involvement with the British International Labour Party an ideological shift or a question of tactics? It is widely believed that it was Padmore who encouraged Nkrumah to consolidate power and move towards the creation of a one-party socialist state. Nkrumah argued that that was the “only” system suitable to Africa.[8] In 1966 the military put an end to Nkrumah’s regime and thereby the last hope and dream of black nationalists of an African homeland.

For the true man of action in the black nationalist tradition, one has to turn to Rodney Worrell’s study of George Padmore, code name of Malcolm Nurse from Trinidad. Worrell had to deal with the fact that James R. Hooker had written a well-reviewed book on Padmore seven decades ago.[6] He met that challenge very well indeed. Padmore was educated at Trinidad’s elite and fully integrated St. Mary’s College. He migrated to the US to attend the segregated Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. This experience and his many confrontations with the vile Jim Crow racism “heightened” his deep hatred of the system and resulted in radicalizing him (22). “Radicalization” led to his joining the US Communist Party, like so many other West Indian intellectuals, but few American blacks. Renowned for his writing and speaking skills, he was soon promoted to then become the first black member of the COMINTERM. Hooker had claimed that memories of Padmore’s life before his involvement in Africa were quickly forgotten and that his entire pre-1957 career was shelved by friends and enemies alike (140). It is the singularly good contribution of Worrell that he restores Padmore’s pre-1957 role. His emphasis on Padmore’s fundamental 1955 book, Pan-Africanism or Communism which reveals his deep hostility towards Soviet Communism, is well done. Padmore describes communist activities and policies towards blacks as opportunistic and hypocritical and blacks generally as revolutionary expendables.[7] That said, Worrell does not resolve the major mystery of Padmore’s “path from communism.” Was his later involvement with the British International Labour Party an ideological shift or a question of tactics? It is widely believed that it was Padmore who encouraged Nkrumah to consolidate power and move towards the creation of a one-party socialist state. Nkrumah argued that that was the “only” system suitable to Africa.[8] In 1966 the military put an end to Nkrumah’s regime and thereby the last hope and dream of black nationalists of an African homeland.

These are important books concerning a problem identified as the Negro Question which is far from solved. That said, they commit two errors of omission: they limit their analysis to the 15% of the region which is English speaking, and they completely overlook the fact that these 15% new black elites have done a commendable job governing democratically and human rights respecting regimes.

This is the black nationalism worth celebrating.

[1] Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1944). Myrdal began his research in 1937 sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation.

[2] See, Jacob A. Zumoff, The Communist International and US Communism, 1919-1929 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2015), 314-315); Duncan Hallas, The Comintern (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 1985), 115).

[3] Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism Revised and Updated Third Edition (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

[4] C.L.R. James, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways (New York: C.L.R. James, 1953), p. 202. Compare to Marcus Garvey, also facing deportation, “If there is one country in the world I love, that country is America.” Robert A. Hill (ed.) Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1983), Vol. I, 506.

[5] John Bracey, “Nello” in Scott McLemee and Paul Le Blanc (ed.), C.L.R. James and Revolutionary Marxism (Chicago: Haymarket Books,1994), 53.

[6] James R. Hooker, Black Revolutionary: George Padmore’s path from Communism to Pan-Africanism (London: Pall Mall Press, 1967).

[7] George Padmore, Pan-Africanism or Communism (New York: Anchor Books, 1972). xviii-xix.

[8] Central theme of his Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for Decolonization and Development (London: Heineman, 1964).

About the Reviewer

Anthony P. Maingot, Ph.D. is a Professor Emeritus and Founding Professor at Florida International University, Miami, Florida. His most recent book is Race, Ideology and the Decline of Caribbean Marxism (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2015).

0