The Book

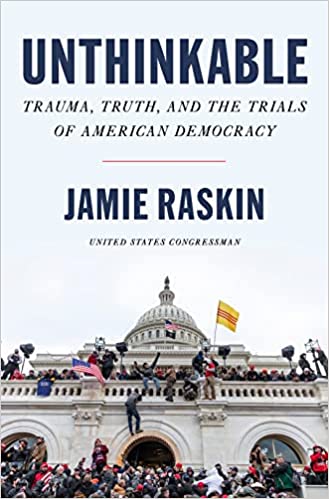

Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy

The Author(s)

Jamie Raskin

Less than a week before the nation watched in horror as a group of insurrectionists attacked the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, Representative Jamie Raskin of Maryland discovered his 25-year-old son’s body in his downstairs apartment. Thomas (Tommy) Raskin had committed suicide. Jaime discusses how he coped with the shock of these events in Unthinkable: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy. Tommy had been at Raskin’s side since before he became a politician. Raskin relates a story about how at a dinner for county Democrats in 2005 a leading official from Montgomery County discouraged Raskin from running due to the likely difficulties he would face with “the Machine.” Eleven-year-old Tommy, at his father’s side, simply asked, “Who’s the machine?” When the official listed four powerful figures, Tommy incredulously followed up with “Well, that’s four votes. What about the other one hundred and sixty thousand” (40)?

Though Tommy became his closest political confidant, Raskin described his son as being “on a path of engagement much closer to that of his grandfather, my dad, Marcus Goodman Raskin, not a politician but a public intellectual” (53). At the time of Jamie’s birth in 1962, Marcus had been in the John F. Kennedy administration, initially serving as national security advisor McGeorge Bundy’s aide before rubbing his superiors the wrong way by calling for unilateral nuclear disarmament and improved relations with the Soviet Union, which led to him being sent to the Bureau of the Budget. In 1963, Marcus and Richard Barnet, a special assistant for disarmament who had met the elder Raskin during a meeting attended by State Department officials and military leaders, created a new progressive think tank in Washington, D.C., the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS). IPS stood at the epicenter of the anti-Vietnam War movement, the civil rights movement, the anti-nuclear movement, and myriad other campaigns for peace, justice, and democracy during the Cold War. Raskin’s involvement in the anti-Vietnam War movement, which led to him being indicted in 1968 as part of the “Boston Five,” which also included Dr. Benjamin Spock, Reverend William Sloane Coffin, writer Mitchell Goodman, and Harvard graduate student Michael Ferber for their involvement in a conspiracy to aid, abet, and counsel draft resistance, fascinated Tommy. Eventually, Tommy held a summer internship at IPS and later worked with Phyllis Bennis at IPS to end the Saudi war in Yemen.

Whereas his father relished the role of public scholar, fusing activism and intellectual pursuits, Jamie entered Harvard University at 16 years old, eventually working his way towards a law degree from Harvard Law. Shortly thereafter, he became a constitutional law professor at American University, a position he held for more than two decades. He won a seat in the Maryland state Senate in 2006, where he remained until entering the House of Representatives in 2017. Nonetheless, despite the different career path, Jamie is as much a defender of democracy as his father.

Raskin’s pedigree makes him an ideal guardian of democracy. In his eulogy, Jamie described his father as “a great citizen of democracy.”[1] Therefore, it is not surprising that in his opening statement during the February 2021 impeachment trial of Donald Trump, Raskin turned to his father’s words: “Democracy needs a ground to stand upon. And that ground is the truth,” Jamie affirmed.[2] For his entire life, Marcus Raskin had fought for truth and democracy. As Raskin began working on a blueprint in 1962 for what would become IPS, he already envisioned the think tank as a promoter of “a democratic society.” He lamented the “authoritarian nature of the twentieth century,” where technological advances, growing nuclear arsenals, and “the seeming complexity of social and political problems have distorted the concept of democracy to the breaking point.” Greater citizen involvement in governing “depends upon the knowledge of the citizenry and its ability to help formulate and choose real rather than pseudo-alternatives,” according to Raskin. He argued that “democratic republican government” required “education” to make informed decisions rather than rely on the “little objective information and mostly invented or colored views” of experts in an “authoritarian government.” In the latter, “the citizen recoils, becomes apathetic and allows the Government (the few) to make the choices for the society.”[3] IPS, in its own small way, would work to empower “the people” by educating the citizenry and serving, in the words of investigative journalist I.F. Stone, as the “institute for the rest of us.”

The “imperial presidency” and Watergate greatly concerned the intellectuals at IPS. Yet for them, impeachment of President Richard Nixon and congressional reforms enacted in the 1970s did not go far enough. Writing in The New Republic in 1974, Raskin described the United States as an “ersatz democracy.” He claimed that due in part to the actions of liberals, who, he wrote, “have become uncomfortable with its [democracy’s] egalitarian tendencies,” America had an oligarchic government. Thus, “liberals have found themselves favoring oligarchy and inequality rather than democracy,” Raskin suggested. He went on to claim that “liberalism has been satisfied with the primitive formulation that each person ‘counts’ in a democracy. Where democratic participation and public deliberation do not precede the ‘counting’ principle, the individual person is merely objectified. He becomes someone who is to be informed, brought up and molded to decisions by ruling elites or impersonal institutions that employ the tools of ‘objective’ science to determine the utility of particular actions and the malleability of the public.”[4] That same year, Raskin proposed reviving the grand jury as it was understood in the eighteenth century, which involved citizens working directly with Congress while hearing testimonies, holding hearings, and proposing legislation. Raskin explained that “the grand jury was used to find out the problems of government and to institutionalize citizen control and participation.” Re-instituting grand juries would, Raskin claimed, “open the way to the emergence of a participatory nation in which citizenship would become the linchpin of a modern American democracy.”[5] It is fitting that Raskin’s son is now using his position in Congress to bring accountability to those in power and preserve democracy. After all, for Jamie, Congress represented the centerpiece of democratic governance. He considers it “the representative voice of the people–and here, the people govern,” he writes (198).

Like his father, Jamie is a believer in pragmatism, particularly as understood by philosopher John Dewey. In 1971, Marcus devoted an entire book—Being and Doing—to developing a modern update to Deweyan philosophy. Marcus called it social reconstruction. Marcus warned that “liberal authoritarianism” had colonized the United States, creating a hierarchical society that deprived citizens of their democratic rights. Social reconstruction involved “the initiation of projects, social inventions, analysis and a new political party that will reconstruct the body politic in a nonhierarchic direction with shared authority,” Marcus wrote.[6] In his own way, Jamie continued this effort. As he explained to a journalist in late 2021, pragmatism “is essentially democratic political experimentation for the common good. That to me is the promise of democratic politics–developing projects to try to make life better for people and transform the human condition.”[7]

On January 6, Jamie’s two crises–one personal, the other political–seemingly merged when he stood up to give his response to the Republican objections to Arizona’s presidential electors. As Raskin began his speech and thanked his colleagues for their condolences, the chamber filled with applause as Congresspersons rose to their feet to express support for Raskin during such trying times. Tommy’s memory also helped Raskin as he fled the marauding rioters later that same day, while also worrying about the safety of his daughter, Tabitha, and Hank Kronick, Hannah’s, his other daughter, husband, who had joined Raskin in the Capitol to watch the certification process. “My trauma, my wound, has now become my shield of defense and my path of escape,” Raskin writes of this moment (34).

Over the next days, weeks, and months, Jamie confronted the profound grief caused by each of these tragedies, which remain linked in his mind. Raskin refers to a “strong bond between parenthood and patriotism” (248). Citizens, like parents nurturing their children, had a responsibility to protect their country. Thus, for Raskin, the impeachment of President Trump offered a way to defend both his son’s memory and democracy itself. “January 6–that stomach-churning, violent insurrection; that desecration of American democracy; that demoralization of all our values; that explosion of seething hatred that caught his sister and his brother-in-law in its tentacles–would have wrecked Tommy Raskin,” Raskin writes (293).

In the aftermath of the insurrection, Raskin saw it as his task “to defend democracy” and “oust him [Trump] and take down the right-wing authoritarianism he had cultivated and that was spreading like a second deadly plague across the land” (186). To this end, Raskin supported evoking the Twenty-Fifth Amendment and impeachment. Raskin’s family had experienced first-hand the danger of a power-hungry executive. He describes the impeachment process against President Richard Nixon as “starkly personal for me” (194). This is not surprising given that his father, Marcus, and IPS co-founder Richard Barnet, had been included on Nixon’s “Enemies List.” Not yet a teenager when Nixon was in the White House, he took center stage during the second impeachment of President Trump when Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi chose Raskin for the position of lead impeachment manager.

Charging President Trump with “incitement to insurrection,” the House voted 232-197 to impeach the president on January 13. Yet, at the end of the day, Raskin looked beyond the impeachment of a single individual and considered how the trial “was about who we are” (387). Though he thought partisanship a sign of America’s freedom of speech, he also urged his fellow politicians to pursue the common good, as opposed to seeking to further partisan causes. He implores his fellow congresspersons “to act as constitutional patriots and place our oaths and commitment to constitutional processes and values way above the narrow and short-term interests of our political parties and way, way above the ambitions of specific power-seeking individuals” (389). Raskin takes solace in the fact that although Trump avoided punishment, the final tally of 57 “guilty” votes was more bipartisan than for any previous impeachment conviction.

After the Republican-led Senate voted against the establishment of an independent commission to investigate the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol in May 2021, Speaker Pelosi created a thirteen-member Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol composed of eight Democrats and five Republicans. Raskin, who is part of the commission, describes its task as two-fold: “to determine the truth and to protect democracy” (410). Beyond the commission, Raskin also demands reform. He labels the Electoral College a “flawed institution,” even more so as its behind-the-scenes processes “have been transformed into new arenas for no-holds-barred partisan struggle and conflict” (414). Boring procedural events, such as the creation of “certificates of ascertainment” by the state governors, are under attack in the face of one conspiracy theory or another. Raskin initially hoped to use the select committee to go beyond investigating the events of January 6 to strengthening and preserving the principle of one person, one vote. As he explained in an interview in late 2021, “Our select committee, I believe, should do whatever it can to reform the Electoral Count Act, to make it conform as much as possible to the popular will.”[8]

Raskin concludes his book by referring back to its title. Of his son, he says, “He dared to think about not only what was unthinkably dreadful in the human experience but also what might be unthinkably beautiful in our potential future, a future he hoped for and worked to bring about so passionately” (422). Tommy shared with his grandfather an optimism about humankind’s ability to overcome its worst tendencies in pursuit of the common good. In fact, each generation of Raskins has fought to protect and expand democracy in an effort to improve the human condition. As Jamie told another journalist in late 2021, “January 6th was not the final act, but perhaps the prologue to a titanic struggle between democracy and violent authoritarianism in America.”[9] Trumpian authoritarianism is only the latest threat to democracy. The family project begun more than a half century ago by Marcus Raskin continues to this day, now led by Jamie Raskin, who also carries on the legacy of his young son.

[1] Jamie Raskin, “Lessons I Learned from My Father,” January 16, 2018, https://ips-dc.org/lessons-learned-father/

[2] Katrina vanden Heuvel, “How to Hold Senate Republicans Accountable,” Washington Post, February 15, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/02/15/how-hold-senate-republicans-accountable/

[3] Brian S Mueller, Democracy’s Think Tank: The Institute for Policy Studies and Progressive Foreign Policy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 2.

[4] Marcus Raskin, “Ersatz Democracy and the Real Thing,” The New Republic, November 9, 1974, 29

[5] Marcus Raskin, Notes on the Old System: To Transform American Politics (New York: David McKay, 1974), 149-151.

[6] Marcus G. Raskin, Being and Doing (New York: Random House, 1971) xvi, xxiii, 209–27

[7] Michael Tomasky, “Jamie Raskin: Democracy’s Defender,” The New Republic, January 3, 2022. https://newrepublic.com/article/164778/jamie-raskin-democracy-defender-profile

[8] Tomasky, “Jamie Raskin: Democracy’s Defender.”

[9] David Remnick, “A Person of the Year: Jamie Raskin,” The New Yorker, December 16, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/a-person-of-the-year-jamie-raskin

About the Reviewer

Brian S. Mueller is a historian, author, and teacher. He specializes in the history of American foreign policy, social movements, radicalism, and the politics of intellectuals. He is the author of Democracy’s Think Tank: The Institute for Policy Studies and Progressive Foreign Policy (University of Pennsylvania Press, June 2021). His current project, provisionally titled Faith & Solidarity: The Central America Peace Movement of the 1980s, will offer the first comprehensive history of the anti-interventionist movement that arose in response to U.S. intervention in Central America in the 1980s. He received his PhD in 2015, and is currently a lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

0