The Book

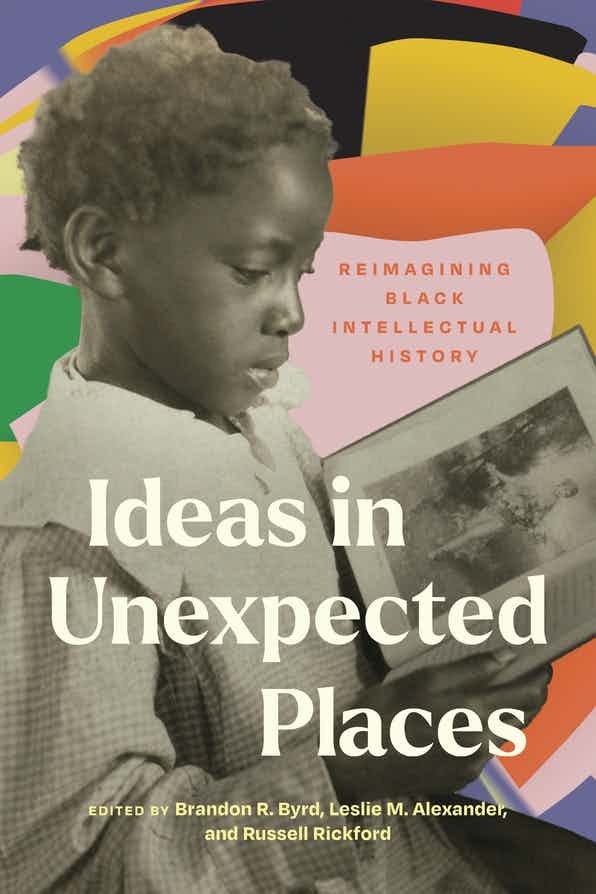

Ideas in Unexpected Places: Reimagining Black Intellectual History

The Author(s)

Brandon R. Byrd, Leslie M. Alexander, and Russell Rickford

In this midst of some resistance to the teaching of African American history in schools and misrepresentations in the media about the teaching of “critical race theory,” we find ourselves in a war of ideas. In this context, Brandon R. Byrd, Leslie M. Alexander, and Russell Rickford’s Ideas in Unexpected Places: Reimagining Black Intellectual History have delivered a volume of sophisticated historical analyses about the ideas and thought of Black people. This new volume offers fresh interpretations of Black history including topics such as slavery, anticolonialism, Black internationalism, Black Power, and the digital age.

An impetus of the volume was the African American Intellectual History Society’s second annual conference in 2017. Hosting an international contingency of scholars from the Caribbean, U.S. and Europe, the attendees were inspired by keynote speaker Davarian Baldwin’s notion of locating ideas in “unexpected places.” The co-editors identify ideas in “unexpected places” in new and traditional archives that include “the voices of Black people who never escaped slavery, who lacked formal education, or who developed their ideas outside of the written text (p. 3).” Thus, the volume’s title “Ideas in Unexpected Places” is highly appropriate. The volume includes five sections: Part 1: Intellectual Histories of Slavery’s Sexualities; Part 2: Abolitionism and Black Intellectual History; Part 3: Black Internationalism; Part 4: Black Protest, Politics, and Power; and Part 5: The Digital as Intellectual: Poetics and Possibilities. The breadth of the book is wide, but the chapters therein provide deep intellectual engagement of ideas across several fields and disciplines.

The co-editors are to be commended for their excellent introduction chapter and exceptionally strong chapters. Their respective chapters reflect the growing rise and significance of Black internationalism in African American thought and intellectual history. For this review, I will not discuss each chapter, but instead will overview three chapters and briefly speak about the volume as a whole. In “Hapticity and ‘Soul Care’: A Praxis for Understanding Bondwomen’s History,” Deirdre Cooper Owens investigates the psychological and physical experiences of enslaved Black women and the authority white men inflicted on their bodies. Enslaved Black women, Owens, argues practiced “resistive life-sustaining” measures to protect themselves and as a show of agency. Owens employs the concept of “soul care” as a framework for interpreting and understanding Black women’s experiences during slavery. She defines “soul care” as “a framework for examining how enslaved women sparked nineteenth-century discourses on ethics and the moral parameters of womanhood.” (50). The concept of “soul care” offers a critical perspective to bring to light black womens’ experience and to view them as both “subjects and agents of history” (51). “Soul Care” is a powerful interpretive tool that contributes significantly to the reservoir of ideas in the Black intellectual tradition.

Marlene L. Daut’s “Anitconquest and the Development of Anticolonialism after the Haitian Constitution of 1805,” demonstrates Haiti’s contributions to the Black intellectual tradition. Daut states “the foundational documents of Haitian sovereignty also challenged the logic and material practices of colonialism in the Atlantic world.” (77). Haiti’s 1805 Constitution was one of those documents referred to by Daut. The constitution includes statements that slavery was abolished, promises not to engage in conquest of other nations, and it identified Haitians as “Black” people. Building on ideas in the Haitian Declaration of Independence in 1801, Daut argues that the 1805 constitution was foundational in anticolonialist thought and inspired Black thinkers in the U.S. Daut’s chapter enhances our understanding of Black anticolonial thought by extending it to the early nineteen century and beyond the postcolonial and anticolonial thought in the 1950s and 1960s. Daut also teaches us that Black anticolonial thought emerged in closer proximity to the U.S. than one might think.

Richard D. Benson’s “A Learning Laboratory for Liberation: Black Power and the Communiversity of Chicago, 1969-78” centers education as a site for Black intellectual production. He argues that Black educators, students, and community organizers in Chicago’s South Side “provided curriculum and instruction that critically intersected with Black life on a local, national, and transnational scale.” (192). This “communiversity” challenged media manipulation and the harms of capitalism, reflecting pragmatic ideas from the Black Power movement. In illuminating the work of the communitiversity in Chicago, Benson reveals the ideas and ideology that served as a “Black alternative curriculum.” (193). As a historian of education, myself, I was pleased to see a chapter on Black education in this volume. This chapter, like the others, speaks profoundly to the current debates about the teaching of Black history in schools.

I could have easily selected any chapter as representative of the excellent scholarship throughout the volume. All the chapters are exceptional and represent the wide range of this strong volume. Anyone interested in how ideas gestate and develop in unexpectated places will find this volume highly informative. The editors have brought together scholars across fields and disciplines and produced a volume that is a major contribution to the fields of intellectual history and African American intellectual history. This volume can also be invaluable for the general public during a time when we need robust and rigorous examinations of ideas in African American history. This volume delivers.

About the Reviewer

Derrick P. Alridge is Professor of Education at the University of Virginia. An educational and intellectual historian, Alridge’s scholarship examines education in the U.S. with foci in African American education and the civil rights movement. His books include The Educational Thought of W.E.B. Du Bois: An Intellectual History and The Black Intellectual Tradition: African American Thought in the Twentieth Century (with Neil Bynum and James B. Stewart).

0