The Book

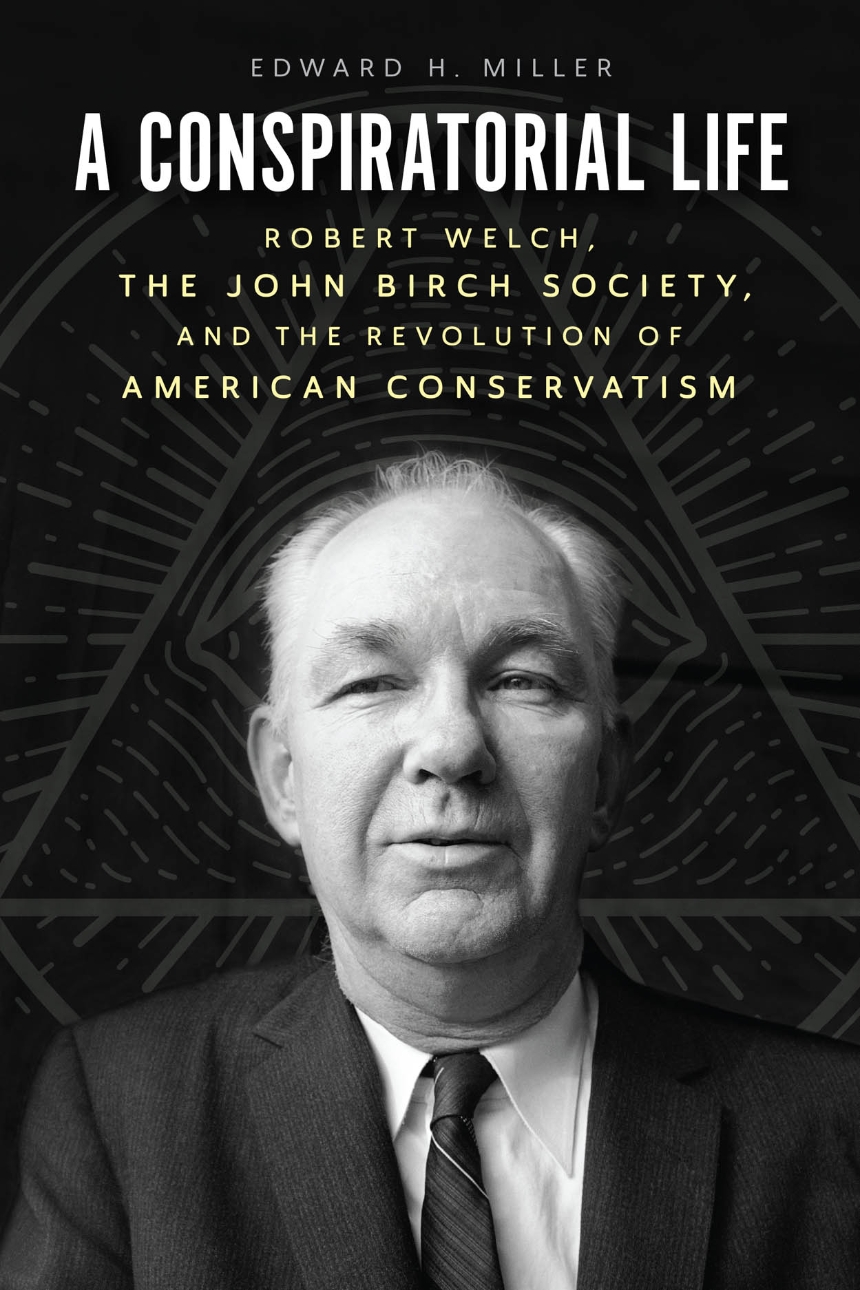

A Conspiratorial Life: Robert Welch, the John Birch Society, and the Revolution of American Conservatism

The Author(s)

Edward H. Miller

Most accounts of the rise of conservatism in the 20th century follow a familiar set of characters: William F. Buckley, Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan. Historian Edward Miller suggests an alternative leading man: Robert Welch. His new biography of the founder and leader of the John Birch Society, the anticommunist grass-roots organization founded in 1958, makes the case that the scholarly focus on the politically respectable right has led to a distorted understanding of the history of conservatism—one that is especially problematic given the prevalence of loony conspiracy theories on the right today. Reaganism has fled the scene, and “we live,” Miller writes, “in the age of Robert Welch.”[1]

A Conspiratorial Life draws on Welch’s private papers, although Miller does not say where these are located, only crediting a “generous” anonymous source for allowing him access (catnip for conspiracy theorists!). It offers many new insights into Welch’s life, and the history of the JBS, while making a compelling case for expanding our vison of postwar conservatism. Yet there’s something frustrating about the easy equivalence between Welch and the modern right. While today’s conservative activists draw motifs from the politics of the mid-twentieth-century, the broader dynamics have profoundly changed.

Welch grew up in North Carolina, the grandson of a slaveholder who had fought for the Confederacy.[2] His father owned a plantation growing wheat and corn, but Welch was never interested in staying on the land, going North to attend Harvard Law School. After graduating, he decided to remain in Massachusetts and start a candy manufacturing company, believing this to be a line of industry in which he could excel with little experience. But his company went bankrupt in the Great Depression, and Welch wound up an employee of his younger brother James—who started his own sweets company that would far outstrip the profits of his older sibling’s enterprise.

Welch’s travails in the 1930s were not just personal but political. He was enraged by the infringements of the New Deal on the autonomy of business, and he opposed entry into World War II, joining the America First Committee. He admired Robert Taft and worked with the National Association of Manufacturers; had he been president of his own company, he might have become a leader of the organization. At this point, he was not yet estranged from electoral politics; Welch even ran for lieutenant governor of Massachusetts in 1950 (he lost).

After World War II, Welch had followed the Chinese Revolution with mounting anxiety. In an effort to fathom why Truman failed to win in Korea, he even traveled to East Asia to meet with anticommunist leaders and activists there. Joseph McCarthy provided a clear answer: Communists had infiltrated American government and were handicapping it from within.

Welch had been a loyal Republican in the early 1950s, always in Taft’s camp, but cautiously optimistic about Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidency. Once McCarthy was censured by the Senate, though, Welch’s disillusionment with the Republican Party was complete. He began to reach out to the friends he had made in conservative circles since his America First days. After a meeting with other conservative activists in New York (Sun Oil president J. Howard Pew and Foundation for Economic Education leader Leonard Read), Welch penned a letter that would eventually grow to book-length, summing up his observations about political life and containing a surprising “surmise:” that President Dwight Eisenhower “could be an actual Communist agent, a disciplined member of the Communist Party who has been acting on orders from the Communist Party for at least 15 years.”[3]

Welch began to send the letter to his friends in the conservative business world, asking them to keep it under wraps. In 1958, he went farther still: He gathered eleven other executives and conservative thinkers in Indianapolis for a two-day meeting that resulted in the founding of the John Birch Society—named for a Christian missionary who had been killed by Chinese Communists a few days after the end of World War II. It was the perfect metaphor for the new enemy emerging where the old one had been defeated. Birch’s family believed that the State Department had hidden the real culprits of his murder, and his story encapsulated Welch’s main preoccupations—the failure of the United States to keep Communism from rising in Asia, and the duplicity and betrayal of the American government in the anticommunist cause.

In starting the JBS, Welch wanted to build a grass-roots network of anticommunist activists. They would not engage in electoral politics, but rather in long-range projects of political education: screening films, running discussion groups, distributing books and articles, publishing a magazine. Modeling its activities on Welch’s vision of the Communist Party in the 1930s, it would organize “cells” of committed members and then run “front groups” that ran more public campaigns, like the 1959 Campaign Against Summit Entanglements that sought to pressure Eisenhower against any meetings with Nikita Khrushchev. Members were instructed to keep their membership secret and keep JBS publications out of sight in case a nosy neighbor stopped by to “borrow sugar”—adding cloak-and-dagger excitement to what might otherwise have been routine.[4]

After Welch’s accusations about Eisenhower surfaced, William F. Buckley and other conservatives distanced themselves from Welch—even as politicians such as Goldwater relied on the support of JBS activists. Welch pretended he didn’t care, but he faced pressure to step aside and let someone else take over the organization—which he staunchly refused to do. Miller describes Welch’s attempt to police the ranks of the JBS to expel vocal anti-Semites whose claims he believed would damage the credibility of the cause, much as Buckley feared that Welch would (even though Welch seems never to have grappled with the ways that his conspiratorial vision explicitly echoed political fantasies about all-powerful Jewish cabals).

Over time, Welch’s emphasis shifted to focus on the civil rights movement, which he saw in global terms—a manifestation of the broader anti-colonial politics of the 1960s. National liberation movements and civil rights were both plots run by the Communists, who sought to foment racial conflict in order to take over. Even Bull Connor’s dogs in Birmingham, Welch insisted, only bit protesters after they were antagonized by Communist agents who knew that the photographs of snarling dogs attacking children would be media gold.

Then in the mid-1960s, Welch changed his position still further. Even the Communists, he began to argue, were “only a tool of the total conspiracy”—a secretive, all-powerful group of “Insiders” who sought to control the entire world through a global government.

Although the JBS is often thought to have had its heyday in the 1960s, Miller suggests that it was able to capitalize on the rightward shift of the country in the 1970s, leading the opposition to sex education in California and fighting abortion rights (Welch believed these were a conspiracy by the “Insiders” to promote actual infanticide of young children).[5] Generous financial support from Nelson Bunker Hunt, a Texas oil millionaire best known for his attempt to corner the world market in silver in 1980, helped the JBS stay afloat. Meanwhile, Welch faced new challenges from within, such as an attack on his leadership from a young member who took the approach of the organization to its logical conclusion and claimed that even the JBS had been infiltrated by Communists.

Miller estimates that JBS membership probably peaked around thirty thousand. Given the many people who participated and who brought all that they learned into countless local political fights, there’s a powerful case to be made for broadening how we think about the history of the 20th-century right—to view Buckley and Reagan as one offshoot of a mobilization that relied centrally on the paranoia-fueled political work of the people Welch inspired. But how to think the influence of the Birchers today? The John Birch Society continues to exist—and by some accounts, it even thrived and grew over the years of Trump’s presidency. The antagonism toward mainstream Republicans, the belief in a shadowy group of “Insiders” who seek one-world government, even the embrace of cultural politics and the right’s insistence that feminism, gay rights and racial equality all hid a deeper political agenda of cultural Marxism—all of this is familiar.

But today’s context seems far from the suburban conservatism of the Cold War years, and despite Welch’s fevered vision, the John Birch Society seems sedate and respectable in retrospect. Its study groups, coffee houses, film screenings and political education efforts were so different in tone from the mass politics of a Trump rally—let alone the Charlottesville march or the Capitol riot. The ranks of the right today include many small businessmen and self-employed people who may resemble the Birchers in certain ways—but the movement as a whole seems driven by a spirit of rage and desperation light years from that which guided Robert Welch and his supporters. In this sense, while the contemporary right may trace parts of its lineage and its emotional framework to the JBS and the anticommunism of the mid-twentieth century, its politics are in other ways entirely new.

[1] Edward H. Miller, A Conspiratorial Life: Robert Welch, the John Birch Society and the Revolution of American Conservatism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 1.

[2] Miller, 17.

Miller, 161.

[4] Miller, 212.

[5] Miller, 359.

About the Reviewer

Kim Phillips-Fein is the author, most recently, of Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics.

0