The Book

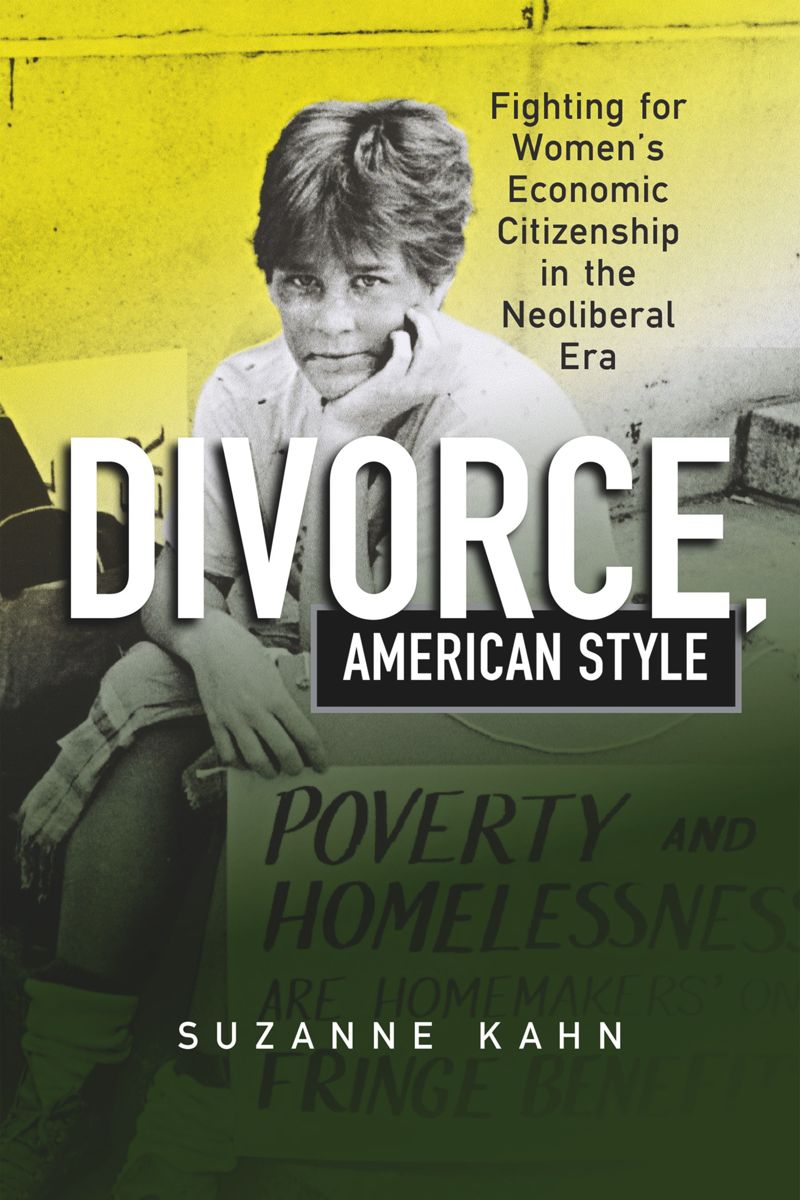

Divorce, American Style: Fighting for Women's Economic Citizenship in the Neoliberal Era

The Author(s)

Suzanne Kahn

Suzanne Kahn offers a fascinating, thorough, and highly readable study of divorce in the history of 20th Century U.S. feminism. The women that emerge, whom she labels “feminist divorce reformers,” fill a unique position at the intersection of the developing U.S. social safety net and the burgeoning feminist movement after the 1960s. They are the women who came to feminism not just in the era of rising divorce rates, but through the unique tangle of hardships that divorced women experienced.

Although married women after the 1960s were pouring into the formal labor force, their fortunes remained chained to their status as wives. Married women’s credit, health insurance, and pensions – their anchors to social citizenship – were dependent on their husbands’ employment and income, and the recognition of that income by the welfare state. Upon divorce, women (and, often, their children) found themselves between the rock of enforced dependency on former (sometimes abusive, poor, and/or remarried) husbands and the hard place of social and economic destitution. The new perspective of feminism, the language of women’s rights, and an expanding network of feminist organizations, provided a toolkit to address this predicament.

Except they didn’t. Over the next several decades, feminist divorce reform – including the National Organization for Women and welfare rights organizations, and their allies in Congress – repeatedly failed to overcome the biases in social policy that insisted on both economically rewarding the married breadwinner-homemaker family (even at great federal expense) and basing welfare support on a narrowly delimited set of valorized statuses. The constrained choices the feminist divorce reform movement faced thus swung between claiming membership in a socially privileged category (wives), and claiming economic benefits intended to incentivize breadwinner-homemaker families. The feminist alternative of recognizing and rewarding economic contributions – and supporting all individuals in need regardless of their family status – repeatedly lost out.

Several historical realities contributed to this decades-long series of disappointments. The welfare state increasingly turned toward the “selective entitlement” model of support – attempting to corral Americans into compliance with conservative social norms – under the fiscal pressures of the constricting safety net spending. And feminism faced a vicious, organized, generations-long backlash running from the anti-Equal Rights Amendment movement of 1970s onward to the antiabortion activism of today.

At the same time, feminist divorce reformers were not just any women. They were generally women for whom the hardships associated with divorce were principal in their lives. That means disproportionately White, middle-class, and (formerly) married. As activists, they were surely sometimes blinkered by privilege, but also compelled to accept less-than-ideal solutions in order to notch political victories and live to fight another day. When the rubber of their economic interests hit the road of neoliberal social welfare policy, the feminist divorce reform movement did what reform movements so often do: it compromised.

Divorce, American Style thus fills (as we say in academia) a much-needed gap in the literature. It provides a rigorously-documented narrative of a uniquely American feminism at a pivotal point in history. It provides important new leverage for understanding how both feminism and social welfare policy got where they are today by focusing on the key intersections between them, as drawn through the legislative and policy debates Kahn explores in correspondence, drafts, committee reports, feminist meeting minutes, news reports, statistical data, and politicians’ pronouncements.

I highly recommend this book.

About the Reviewer

Philip N. Cohen is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Sociology Department at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research and teaching concern families and inequality. He writes about demographic trends, family structure, the division of labor, and health disparities. His commentary on topics ranging from race and gender inequality to parenting, poverty, and popular culture has appeared in outlets such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Atlantic, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and the New Republic. The results of his research have been widely reported in major media, and he often comments on new research or trends in the news. His popular textbook, The Family: Diversity, Inequality, and Social Change, is now in its third edition. For three years he was co-editor, with Syed Ali, of Contexts, the public-facing magazine of the American Sociological Association. Since 2016, He has been the founding director of SocArXiv, an open archive for the social sciences, and an advocate for open science in the research community. He is active in efforts to reform the system of scholarly communication, and often speak on the topic of how scholars can productively engage with our many public audiences, to improve our work and deepen its impact. He is working on a new book, titled Citizen Scholar, to be published by Columbia University Press.

0