Last August, I ordered a used book from a bookseller in the United Kingdom: John H. Gleason’s 1950 study, The Genesis of Russophobia in Great Britain. I knew I would need the book for my chapter on the Crimean War and the idea of “Western Civilization,” but I wasn’t ready to turn to it yet.

Now, instead of turning to this topic, the topic is turning to me, to all of us, thanks to current events.

“Current events,” it just now occurs to me, is a sort of exasperated rhetorical handwaving gesture historians make about the right-now, the one-damn-thing-after-another in the present that we will some day be history, and that we’d love to be able to think about historically ourselves if we weren’t right in the middle of it

. The problem for historians is that as we tidy up one little corner of the timeline the debris keeps piling up. I can’t even muster the energy to organize my laundry room; what in God’s name am I supposed to do with the chaos of “current events” except to hope that some poor sap fifty years from now brings some order to the mess.

Anyway, current events being what they are, it’s a timely work to read just now.

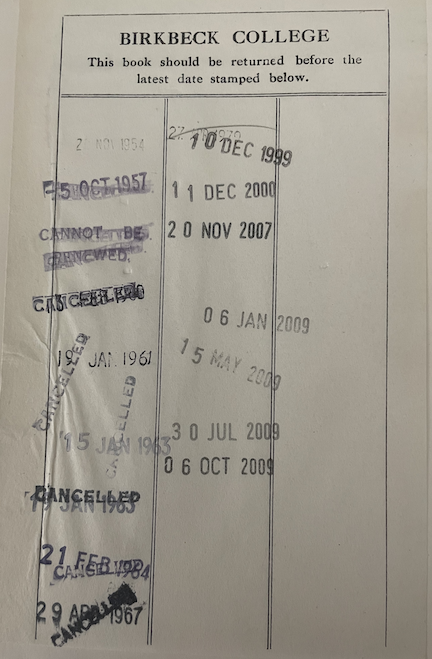

Library due dates and cancellation stamps in a Cold War work of scholarship on Anglo-Russian relations.

My particular copy of the book was withdrawn from the library of Birkbeck College at the University of London. In the back of the book you can see the due date stamps for every time the book was checked out of the library, from 2 Nov 1954 to 6 Oct. 2009. I believe the book was deaccessioned soon after that, because I found a movie stub used as a bookmark inside the book dated from earlier that year, so I’m guessing no one else used it after that. In fact, it was chekced out four times between January and October of 2009—I’m guessing either a professor or a grad student was using this book for research.

I am also guessing that someone at that college today dearly wishes that the library had a copy of this book. But in 2009, who knew that the souring of Anglo-Russian relations between 1815 and 1840 and the polemical run-up to the Crimean War would be a hot topic again, something needed to explain “current events”?

Anyway, it’s clear to me that it’s time to read this book that has been sitting on my shelf since last August. I will report back.

In the meantime, here is the first paragraph of the introduction, an interesting artifact of the Cold War:

Few matters can be of greater importance at the present day than the establishment of mutual trust and toleration between the Soviet Union and English-speaking peoples. It is my hope that the present study of the origins and early development of Russophobia in Great Britain may in some slight measure foster such sympathy. The story is one of the disruption of cordiality and the growth of hostility between Russia and the United Kingdom at a time when the basic foreign policies of the two nations were, if not identical, at least complementary. It is to be hoped that relatively trivial disagreements will not again perpetuate a lack of mutual understanding and thus induce insuperable fear and hatred.

What is happening in Ukraine is hardly the result of a relatively trivial disagreement. Would that it were! Instead, we are getting a reprise of something awful. But what? Cold War, World War II, World War I, Crimean War, Great Power imperialism? All of the above? Something old and something new, something bloody, something blue? It almost doesn’t matter, except it matters very much.

Everything old is new again, before historians or librarians even have time to turn around.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Instead, we are getting a reprise of something awful. But what? Cold War, World War II, World War I, Crimean War, Great Power imperialism? All of the above?

The question you pose — I recognize it’s partly a rhetorical question, not therefore one that especially expects to be answered — has probably been taken up in some commentary I haven’t read, but I’ve not seen a lot of discussion of this particular question.

I don’t think we’re going to see a reprise of WW1 (except insofar as there was, before the invasion, trench warfare in the Donbas region between separatists and their opponents). Nor a reprise of WW2. (A conventional all-out war on a global scale would be difficult to imagine today, given for one thing the existence of nuclear weapons.)

So if not WW1 or WW2, is this a reprise of the Cold War? Well, it lacks the particular ideological elements of the Cold War, with Putin’s nationalist revanchism substituting for Soviet Communism. It also lacks an Iron Curtain dividing Europe, etc.

There is probably one old-ish feature of international relations that has come more to the fore in the current situation, the notion that great powers sometimes engage in what Hedley Bull, in his classic The Anarchical Society (1977), called “the unilateral exercise of local preponderance.” Bull thought this contributed, at least sometimes, to “international order,” which is really only true if one has a kind of top-down view of international order — and even then, it’s not always the case. It’s especially not the case, it seems, when the unilateral exercise of local preponderance involves an outright invasion of a sovereign state that the great power sees as being in its sphere of influence, or if Putin’s speeches are taken at face value, sees as being part of the great power itself.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the invasion (from my standpoint at any rate), despite the warnings of U.S. and other intelligence agencies, was how it ran against expectations. The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 was a case of unlawful aggression, but it occurred in a part of the world, the Middle East, where armed conflict is common, and where interstate war (see Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, Arab-Israeli wars etc., current war in Yemen, though that’s an internationalized civil war) can’t be seen as completely obsolete. In Europe, by contrast, interstate war could have been seen as obsolete. There hasn’t been a “classic” or archetypal interstate war in Europe since WW2 (the wars in the former Yugoslavia were awful, but they don’t really count as interstate wars in my book). The Soviet (and Warsaw Pact) uses of force in Hungary and Czechoslovakia don’t count as interstate wars either. So (unless I’m forgetting something), this invasion is the first thing of its kind in Europe since WW2. From a historical standpoint, that’s significant. Also significant is the international reaction. The UN General Assembly vote to condemn the invasion was overwhelming (141 member states voting for it, 35 abstaining, only 5 voting against).

So in a sense “everything old is new again,” but in another sense the old cannot really become new, because the collective understanding of what is acceptable international behavior has arguably changed. In 1977, Bull thought that war could, in certain cases, have an “order-preserving” function, as in wars of self-defense or “law enforcement,” wars to preserve the balance of power, and, “more doubtfully,” wars to bring about “just change.” (p. 189) In 2022, not so much. Civil wars are still relatively common, but “international society,” to use Bull’s phrase, increasingly sees interstate war as illegitimate and beyond the pale, whether it’s war between small countries or between a relatively small one and a big one (here, Ukraine-Russia). From this perspective, the hopeful spin on this utterly horrible event (if such a phrase is not too paradoxical sounding) would see it as one of the last gasps of an obsolescent phenomenon. I’m not saying that is the only way or necessarily the right way to see this, but it is one possible way.