My apologies in not returning to my previous post on “Gloaters and Brooders”—and to this loose series of posts, which I’m calling “Profiles in Complexity”—earlier. The end of the semester is always a challenging time, but this year “challenging” really fails to describe the exhaustion of a year-plus of constant adaptation and anxiety.

I am especially regretful about not returning to the post because it received a number of exceptionally insightful and probing comments. I’ll start, then, by responding here, rather than in the comments section.

In the first comment, Louis responded to my argument that Ira Katznelson made a choice to frame his book Fear Itself as a tragedy, with FDR forced into a dilemma, what I paraphrased, as “What would you do, in other words, if you were forced to choose between working with Theodore Bilbo or letting Hitler destroy global democracy?” Louis asked,

while Katznelson did not have to ask that specific question, wouldn’t any book about the New Deal have to address in some way the choices and dilemmas FDR faced? That would not *necessarily*, I suppose, lead to the kind of tragic perspective you say Katznelson has, but some effort to confront FDR’s choices (and perhaps motives) would seem unavoidable. (Otherwise it’s sort of like, to put it glibly, Hamlet without the prince.)

Robert Westbrook actually offers an indirect answer to Louis’s question in his comment, arguing that FDR and other northern New Dealers were not as conscious of the existence of a moral dilemma between racial justice at home and antifascism abroad as Katznelson tries to claim.

One of my complaints about Katznelson’s story is that, while the course of the New Deal may well be tragic to him since, as he sees it from our time, it failed to reconcile the preservation of democracy with racial justice, he fails to demonstrate that New Dealers felt much torn at all between these two ideal ends. Katznelson renders FDR and other Northern liberals as actors fully alert to their various tragic dilemmas. I question not only his account of the dilemmas but also his portrait of the New Dealers’ moral sensibility. The “dirty hands” defense of one’s subjects (what I call the “frame of consolation”) such as that Katznelson offers is far less compelling if these subjects fail to see in some anguish that their hands are dirty, however obvious it may appear to a later historian to be the case.

What I take from this is the necessary critique of history writing that the “choices” or “dilemmas” that we see in retrospect may not have occurred to the historical actors as actual conflicts—either in practice or in principle. We intellectual historians as a tribe of writers are very talented at introducing tension and complexity because we are trained to look for it. Generally the written record of anyone who puts down a lot of their thoughts on paper—in speeches, letters, books, poems, essays, songs—is bound to give us enough material to construct a case for complexity, to read into their intentions and motivations an ambivalence or painful conflictedness that might be our imposition rather than something that was intellectually or emotionally available to them.

Yet Robert Westbrook also questions my argument that we should move away from this tragic frame, as he argues that it is both valuable and inescapable.

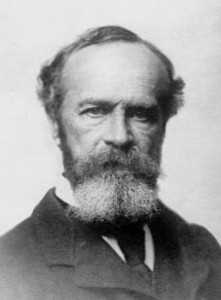

If historians are going to write the stories of moments of great moral import, they can hardly avoid tragic narratives since as William James [says] most such moments require that human beings “butcher the ideal” of a full reconciliation of competing commitments. Intentions are essential to such stories (you cannot butcher this ideal if you do not strongly feel the pull of the competing commitments that comprise it) if we historians are going to credit our subjects and not only ourselves with a tragic consciousness of their actions.

Westbrook’s reference to James is pregnant with meaning. It comes from the collection of essays The Will to Believe, and that is essentially what I think is at stake here: the desire to put a tragic frame around history is a way to maintain history as a form of knowledge that vindicates a robustly voluntaristic understanding of humanity. More simply, historians who choose or value tragic frames in history do so because they have a passionate urge to assert and validate the existence of free will. (“My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will!”)

Before anyone casts me as a determinist, let me explain my objection here. It is not to the belief in free will, but to the way that this view of history centers free will, taking it as both a sine qua non and a ne plus ultra: it is the alpha and the omega of this mode of history writing, even as it does its work silently (in the same way that the basic foundations of any paradigm operate). It makes the belief in free will into a metaphysical drama, something one cannot be ambivalent about but must fight for, even proselytize.

We can look back at much of what I’ve described as “the problem paradigm”—the moral and intellectual investments in adding “complexity” to the past, the eagerness to encode certain coincidences in history as “ironic” or “tragic” (it’s only ironic if there’s intention involved), the fixation on intentions and motives—in just this light, as parts of a deeper agenda to make of history a vindication of the will to believe.

And here is where we can historicize, because this desire for a historiography centering free will was a response to particular historical conditions, particularly within the academy. But before I move in that direction, let me pause to rearticulate what I am saying in a different way so that my perspective—my values or commitments—is clear.

Let us take the famous saying of Marx from the Eighteenth Brumaire: “Men[1] make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” One can certainly look at that statement as bearing a heavy weight of tragedy—this is not how it is supposed to be! Humans are supposed to be freer than this! Under such circumstances we can never live up to the dictates of our conscience—we can never make our choices align perfectly with our principles because our hands are always partially tied.

But one can also look at this idea as merely a statement of fact: this is how things are, and it is up to us to decide what we can make of what limited freedom we have. It is not tragic that we our will, though free to recognize what is right, is restricted to doing what is possible.

To be clear, I am not saying that the former perspective should be eliminated from the writing of history. What I am saying is that looking at history from within this particular worldview is a choice—it is not the natural or only way of thinking about humans acting in time. I personally find it faulty on an analytical level and uncongenial on a moral level—it smacks too much of a very Protestant understanding of free will for me, to be frank—but all I am asking for is some self-awareness that it is not the only way to “do” history, that this “problem paradigm” is the product of a particular historical moment.

As a preliminary sketch, the intellectual landscape that produced this mode of historiography can be blocked out in a few strokes. The first and most important is that it was a response to the massive prestige of mid-century social science, with its gigantic systems and all-encompassing schemas. The claustrophobia that permeated history departments as some practitioners tried to import these ambitious formalisms and structuralisms and functionalisms has been well attested: we all know the story of how the cultural turn hacked out a path for historians fleeing the reign of cliometrics.

But there was something deeper at work than just a resistance to the quantitative, or a frustration with the intellectual arrogance of the “hard” social sciences. The association of modernization theory—and the large chunks of the academy that went with it—with US imperialism was certainly part of it, as was the counterculture’s critique of social stultification and its praise of spontaneity and willfulness. These factors would continue to animate historiography, I’d argue, well after their immediate contexts had passed—permanently shaping the sensibilities of historians who came of age in the Seventies and early Eighties.

To get beneath these rather obvious influences, however, is difficult, and I have run on long enough for this post. I apologize to Bill Fine for not being able to address his comment, although it’s quite possible that Louis and Robert Westbrook will feel that I didn’t adequately address theirs either!

Notes

[1] To be pedantic, Marx used the gender-neutral Die Menschen: “Die Menschen machen ihre eigene Geschichte, aber sie machen sie nicht aus freien Stücken, nicht unter selbstgewählten, sondern unter unmittelbar vorgefundenen, gegebenen und überlieferten Umständen.” To go a bit further, I think the materiality of “sie machen sie nicht aus freien Stücken” is lost in the standard translation. Perhaps idiomatically, “as they please” is fine, but “from free pieces”—the most literal rendering—suggests the fantasy of an artist whose unlimited freedom to create with whatever materials they wish or can imagine that Marx is explicitly denying. We don’t get to choose our materials.

7 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

“It is not tragic that our will, though free to recognize what is right, is restricted to doing what is possible.” Yes, it is. The very definition of a tragic act (as James and I understand it) is that it fails fully to reconcile competing goods or avoid contrary evils. “This is how things are, and it is up to us to decide what we can make of what limited freedom we have.” Yes, this perspective is at the heart of a tragic sensibility (tied to hope not optimism). But, that said, it is always a matter of more or less butchering. To say “I had no choice; I was the prisoner of circumstance (or structures or epistemes)” invites complacency and more rather than less butchering of competing ideals. The best history (and social science), to my mind, centers on the interplay of structure and agency (what Anthony Giddens called “structuration”). Of course, one can find many social theorists who would thoroughly minimize agency, and advance what Foucault termed the erasure of “man.” So perhaps you are right. Keeping agency (and tragedy and irony) alive may be a humanist protest against the mid-century anti-humanism of Levi-Strauss, Foucault (at one point), Althusser, and others. So much the better, I say. Proud to march in that parade alongside Marx, Simmel, Weber, Giddens, Berlin, Bourdieu, and Unger. “Permanently shaping the sensibilities of historians who came of age in the Seventies and early Eighties.” Yes, guilty. And unrepentant.

I’ll make a couple of brief remarks that won’t really directly or fully address Andrew’s objections to “the problem paradigm.”

I agree with Robert Westbrook (and Giddens; see, e.g., his The Constitution of Society) about the interplay of agency and structure. Of course, as Westbrook — I think — implies, there are probably times when structures are (objectively) more constraining and times when they are less constraining. It depends on the particular historical episodes, events, decisions, or problems (!) one is examining.

In a related vein, some historical figures appear as more “tragic” than others, and thus a historian might want to use the word “tragedy,” or stress “tragic” dilemmas, more when discussing those figures. Even if one doesn’t much like “the problem paradigm” and its assumptions, there are some historical actors who just seem to have “tragedy” written all over them, perhaps because the “structures” seemed to constrain their “agency” severely — or at least, they perceived themselves to be constrained in that way. One classic example, I think, is LBJ. Eric Goldman even wrote a book called The Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson. He just seems like a tragic figure if one is familiar, to some extent, with the period in question. That’s certainly not to excuse or defend his choices, or to deny that he had choices, but just to recognize that the dilemmas he saw himself as facing were agonizing for him. That well-known photograph of him holding his glasses in one hand and looking down at a table, with his head in his other hand, says it all pictorially.

In my comment last time I made the mistake of putting you in the free will camp. The current post is cleaner, and it’s probably good that in focusing on the description of a metaphysic, you omitted the feints to issues of identity and power. They confused me, if no one else.

I think I see you’re not corralled by the hoary free will vs. determinism binary [“all I am asking …,” etc]. “The desire to put a tragic frame around history is a way to maintain history as a form of knowledge that vindicates a robustly voluntaristic understanding of humanity.” This insight may prove useful as you continue to historicize it.

But you need to conceptualize the more-than-free-will that’s needed to generate tragedy, where agency is sometimes exaggerated but often conflicted and always limited, actions are taken with limited knowledge of ambiguous or contradictory circumstances neither chosen nor controlled, and intentions are often unrecognizable in their consequences. Agency is imperfect at best, yet somehow ennobling.

To this point the distinction between the two positions hasn’t been clarified very well. On the one hand, the free will thematic as described leaves out most of what makes free will tragic, or at least problematical, minimizing empirical complexity to save moral complexity, to use your earlier terms. How can free will convincingly generate even that – which alone falls short of the tragic – unless its enabling conditions and antagonists are better laid out?

On the other hand, in affirming the not-determinist view, you let choice in through the back door, in two ways at least: 1st – the reality of things is such that we do have some freedom [“’it is up to us to decide what we can make of what limited freedom we have.’ Yes,…”]; and 2nd – though the historiography may be the “product” of a particular time and place, historians at least can step outside, or against it. [But in Kuhn, people never choose a paradigm, no matter how pragmatically affirmational.]

The result is a distinction with little more than an unclarified difference. It’s confusing for your readers: paradigms are in the air, but in the end they opt for the really interesting pluralist parade, with a dazzle of agency over here, and the drumbeat of structure over there.

If we are going to think about tragedy, let us go back to the Greek goat plays, where a protagonist is destroyed because of his nature, NOT because of the choices he has made. *Oedipus the King* begins with a plague striking the city. Neither the doctors or the soothsayers know what to do because the pest has never been encountered before. Their failure enrages the king, who got where he is by imposing his ideas on everyone who has opposed him, whether male authority figure like the older man he encounters at the crossroads or supernatural monster like the Sphinx. Oedipus is a jerk of course. In the play, the critical scene is when Tiresias, a magic man, comes down from the mountains to inform the king that he alone brought the plague. Because Oedipus has always been determined to impose his will on whatever and whoever he can, the cause of the crisis lies in the very actions that raised him above everyone else. His choice is his destiny, fulfills the structuration determining how everybody in the play relates to each other and the supposedly free choices they make when they face crisis. Tiresias insists the plague will rage uncontained until the king changes his ways. Oedipus responds with rage. The only path he is able to follow is to force the future to follow the route his desires demand. Whatever contains him will destroy him, but radical detachment from conventions from social conventions symbolized in killing his father and marrying his mother eventually destroys him as well. The script seems pertinent to the contemporary situation. The chorus in the play, that is to say, the citizens of Thebes witnessing the action of the drama, move from respectful hope that their king will defeat this plague to suspicion that he might in fact be the cause of everyone’s misery to open rebellion and the choice of a new king, less gifted in every way but accountable to the citizenry precisely because he is is a mediocrity. Oedipus, even in humiliated defeat, cannot accept that the citizens might select a man as unimaginative and boring as Creon to be their leader. The tragic, I would submit, is not, at least as understood in classic drama, never a question of free will and wrong choice, but of destiny determined by one’s place in the structure of “things”–however one’s theoretical bent inclines one to define that, but if we follow the logic of tragedy, that choice is not one of free will but of place in a larger institutional structure.

OK, fine. Use the term in that (relatively narrow) way if you wish. But usage changes over time. According to my OED, from the 16thc forward “tragic” has escaped the bounds of classical drama and come to mean simply “Relating to or expressing fatal or sorrowful events; causing sorrow; extremely distressing, sad.” Since at least William James (“The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life”) some moral philosophers (including analysts such as Michael Walzer of the “dirty hands” issue in just war theory) have focused on a particular kind of tragedy in this broader sense: that sorrow, distress, or sadness engendered by the oft-encountered experience in the moral life of choices in which competing ethical ideals cannot be fully reconciled, and the cost to one will be greater than that to the other(s). As James said, “The actually possible in this world is vastly narrower than all that is demanded; and there is always a pinch between the ideal and the actual, which can only be got through by leaving part of the ideal behind.” This is the sense in which Katznelson uses “tragedy” (and Seal rightly understands Katznelson’s usage–as do Louis and I. Not sure about Fine.) As James reference to “the actually possible” suggests, tragedy can often be, in part, the consequence of conditions not of our own making. But, as Seal notes, James was not a philosopher about to remove human free will from the equation altogether (on this see his “Dilemma of Determinism”). What Louis and I are pleading for Seal to acknowledge is the interplay of agency and structure in the moral life–and the often “tragic” (in the now widespread vernacular meaning of the word) consequences of that interplay.

Robert,

Thank you so much for your responses here. I think where I demur from your position is in the question of whether tragedy is an intrinsic or extrinsic property of a set of conditions. My argument is that it is something we impose from the outside, that as historians we choose to call something tragic when we imagine a different past in which the historical actor in question (whose point of view we often identify with) were freer to act than they in fact were. Katznelson wishes that FDR had been freer to disregard Southern Democrats’ votes, that he had been less subject to the necessity of keeping the South in his camp. (Again, your question of whether progressive New Dealers really saw the limits of the New Deal as principally defined by Southern racism is extremely important here.)

I think there are better and worse ways for historians to do the work of imagining alternative pasts, and my view is that typically when historians reach for the tragic frame, they are not likely to be very rigorous or systematic in posing a counterfactual. I think this is because history as a discipline has been generally suspicious of well-developed counterfactuals; economists have been far more likely to engage in this kind of work. At any rate, a historian’s point in invoking the tragic frame often seems to have much more to do with declaring their own political commitments than with investigating genuine alternative paths that were spurned or unrecognized by the historical actors in the moment. I am, in other words, skeptical about what knowledge is gained by the act of invoking the tragic frame.

I wholeheartedly agree, Andrew, that tragedy can be a frame imposed by historians in situations where it does not apply. Such was the burden of my criticism of Katznelson’s adoption of the frame. But that is not to say that there are cases in which the frame is utterly appropriate (maybe this is what you mean by an “intrinsic” property of a set of conditions). All you need is agents torn between two (or more) competing ideals strongly held in a situation in which the demands of neither can be fully met without sacrificing the demands of the other (what James called “butchering the ideal”)—often because of constraints beyond the agents’ control. James (and I) hold that such situations are a (sadly) commonplace feature of human moral life. Historians do not have to impose it on a situation, they may well find it there in the evidence available to them. (Among the crucial pieces of evidence is what John Dewey called the “dramatic rehearsal” of consequences that agents undertake prior to moral action, which can be difficult for historians to find.) Then we argue about whether or not the evidence of their finding is convincing (as Katznelson and I have done). In sum, I am not asking you to abandon your criticism of historians who reach too readily for the tragic frame (I have made such criticism myself), but rather to acknowledge that human experience is filled with tragic episodes that historians are bound to come upon and to feel compelled to narrate as such. And to conclude on a positive note, I agree with you that counterfactuals can be an important tool in such investigations, especially for historians who suspect that the agents they are studying were themselves too ready to reach for a tragic frame in justifying their actions. The (very) difficult task for historians is to exercise moral imagination and judgment in their work without falling prey to anachronistic moralizing.