Editor's Note

Today’s guest post is by Zoie Horecny, who is a 4th year PhD student in history at the University of South Carolina. She earned her MA in Public History at UofSC in 2021. She has spent almost a year working for the Pinckney Papers Project, which is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Zoie is interested in the history of slavery, the Atlantic World, local history, and intellectual history. In 2020, she was awarded the Walter Edgar Scholarship by the Colonial Dames for her work in early American history. In 2021, she was the Thomas E. Davis Scholarship recipient for her work on the American South in a transnational context.

Joshua Gordon (1765-1845) is best known by mainstream scholars for his twenty-two-page, handwritten manual, Witchcraft Book (1784).[1] His guidebook describes cures, ways to care for livestock, and how to identify a neighbor who wishes you harm. But to local historians and genealogists in Lancaster County and York County, South Carolina, Joshua Gordon is a well-known local figure who happened to write a witchcraft manual. He was a prominent enslaver, church member, and childhood friend of President Andrew Jackson.

His life beyond his most notable intellectual product is demonstrative of the Atlantic Word, despite his inland location. As the son of Scots-Irish immigrants, Gordon travelled down the Great Pennsylvania Wagon Road from Lancaster, Pennsylvania as a child.[2] They settled in the Carolina backcountry. Later, Gordon, like many in the Carolina backcountry, supported the Patriot cause in the American Revolution. He was injured in Sumter’s Defeat and used his pension to further his interests in agriculture, and later in becoming an enslaver.

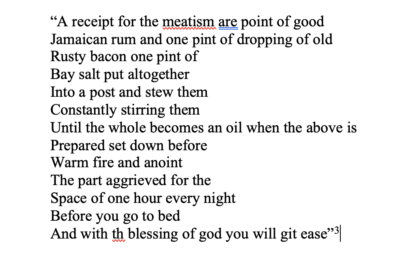

After the war, Gordon returned home to work in agriculture, writing down his tricks of the trade in Witchcraft Book. Gordon’s practice was connected to enduring Western traditions in the occult, but at the time was still considered emerging medical knowledge. His spells explore how early frontiers connected to an Atlantic economy:

Witchcraft Book is intellectually and materially linked to the early modern Atlantic World. Gordon listed material like “Jamaican rum,” only available through long distance trade. [1] While the backcountry was often labeled as pre-modern or ignorant by outsiders in this time period, his experience demonstrates reliable access to goods.[2] Gordon employed modern techniques like using clock time. In addition, Gordon’s techniques not only embodied beginnings of modern scientific standards but are also religiously inclusive. He sought religious affirmations in this cure. The lines between magic, science, and religion are nuanced, flexible, and blurred in this early modern moment.[3]

Beyond using Atlantic trade routes, Gordon had connections within the interior of North America. The manual features an “Indian Cure” for sick children that he learned from a man who was a prisoner of an unnamed indigenous group for five years.[4] He described them as “a nation who lived in new penseelvaney and on a river named white river.”[5] His fragmentary detail offers some evidence to where this cure originated. The White River ends east of present-day Muncie, Indiana on the Ohio border. People such as the Delawares began moving west from the colony of Pennsylvania to this area, as European colonizers and conflict pushed them off their traditional homelands.[6] Tensions culminated in Pontiac’s War in 1763, in which the Delawares, among others, participated in ritualistic raids in the backcountry from Pennsylvania to North Carolina.[7] They captured up to approximately two thousand men from the 1750s to 1760s. Due to British negotiations, hundreds of these men were released in 1764.[8] Perhaps Gordon’s source was one of these men? The Ohio border is a long way from the backcountry of South Carolina, but this is plausible in the well-connected colonial frontier. By examining texts from this period about indigenous people with a critical eye, historians can better detail and understand how and where indigenous ways of knowing disseminated.

However fascinating Gordon is not a niche, occult practitioner. He later embodied the codification of a slave society in South Carolina. By looking at census data, at the time of his death he enslaved at least twenty-four individuals on his plantation (which was originally a Catawba land lease) on Six Mile River.[9] He was a part of a growing class of slaveholding elite in the upcountry.[10] His occult activities did not exclude him from being a founder of Six Mile Presbyterian Church, where James Henley Thornwell developed and began preaching religiously based, pro-slavery ideology.[11] Although he was a colonizer and an enslaver, Gordon coveted occult practices, despite their fading mainstream popularity.[12]

When examining the scope of his life, Gordon has many contours. He captures the experience of settlers and their children, who populated the backcountry, making it a culturally diverse place. But ultimately, the process of colonization is not one simply of cultural exchange.[13] Gordon found a place to rely on his occult traditions, but also a place to exploit native land and participate as an enslaver in an Atlantic economy.

[1] Joshua Gordon, Witchcraft Book. South Caroliniana Library (SCL), 1784; Jon Butler, “Magic, Astrology, and the Early American Religious Heritage, 1600-1760,” The American Historical Review 84, no. 2 (1979), 337.

[2] Letter from Charles Gordon to Louise Pettus, 5 June 1957, Louise Pettus Collection, Winthrop University

[1] Joshua Gordon, Witchcraft Book.

[2] Charles Woodmason, The Carolina Backcountry on the Eve of the Revolution: The Journal and Other Writings of Charles Woodmason, Anglican Itinerant ed. Richard J. Hooker (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953.

[3] Catherine L. Albanese, A Republic of Mind and Spirit a Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007; Wouter J. Hangraaf, “How Magic Survived the Disenchantment of the World.” Religion

, 33 (2003): 357-80.

[4] Joshua Gordon.

[5] Joshua Gordon.

[6] The Delaware name designation broadly defines Indigenous peoples who descended from the Delaware River who referred to themselves in this area as the Lenape.

[7] Amy C. Schutt, “Defining Delawares, 1765–74.” in Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 112.

[8] Matthew C. Ward, “Denouement: ‘Pontiac’s War,’ 1763–1765,” In Breaking the Backcountry (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), 219-254.

[9] Year: 1840; Census Place: Lancaster, South Carolina; Roll: 512; Page: 390; Petition of Joshua Gordon, ca. 1810,” South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 176.1 0010 004 ND00 66714 00

[10] Rachel N. Klein, Unification of a Slave State: The Rise of the Planter Class in the South Carolina Back Country. University of North Carolina, 1990.

[11] Blanche M. Paul, “Works Progress Administration Survey of State and Local Historical Records: 1936,” 1; Eugene Genovese, “James Henley Thornwell and Southern Religion” in Abbeville Review, May 5, 2015; James O. Farmer, The Metaphysical Confederacy: James Henley Thornwell and the Synthesis of Southern Values (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1986).

[12] Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People. Cambridge, (MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

[13] Aime Cesaire, Discourse on Colonialism (Monthly Review Press, 2001), 31-46.

0