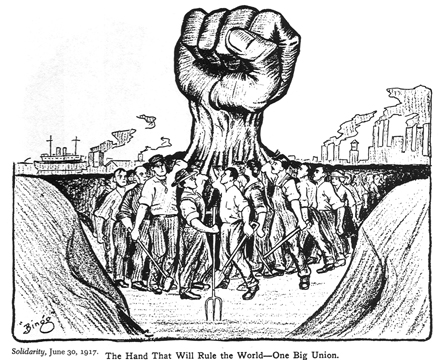

The Wobbly core belief in One Big Union and the solidarity of the working class found support in Whitman’s reference to “the knit of identity” in “Song of Myself” which refers to his approach throughout the poem of blurring the distinctions between individuals and himself, pulling all people together into a common country, a common experience, a common humanity. His terror that the One Big Union that he loved so much (the United States) would be torn asunder by the Civil War led him to repeatedly champion the value of collective experience. Socialists reading Whitman’s references to the unity of America and the solidarity of the working class could easily extrapolate from these references a celebration of the union movement.

In addition, Whitman’s anarchist memes can be found in the I.W.W.’s commitment to educating its members so that they would be capable of operating as powerful and purposeful human beings. Whitman repeatedly voiced his support of public education. These ideas are also present in Emma Goldman’s anarchist reading of Walt Whitman which posits that social transformation is only possible if preceded by personal transformation. To accomplish this feat of mass education, the Wobblies mobilized the socialist press to produce books for the masses. Fulfilling Whitman’s dream of a small edition of his poetry published for the masses, a Little Blue Book version of Walt Whitman’s poems was among the first volumes to be found in the socialist HaldemanJulius publication catalog. The I.W.W. actually distributed to workers Little Blue Book editions of Whitman’s poems, and many Wobblies traveled with a copy of Whitman’s poetry in their packs and read him avidly. In their goal of educating newly-arrived immigrants, the Wobblies established schools and libraries, and even published a grammar book which featured Whitman’s poetry in its exercises. Thus newly-arrived immigrants who might soon become members of the I.W.W. were nursed on the mother’s milk of Walt Whitman’s poetry. Wobbly organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, martyred Wobbly Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Wobbly songwriter Ralph Chaplin, and Wobbly poet Arturo Giovannitti all claimed Walt Whitman as an inspiration. This infusion of Whitman into the Wobbly culture produced echoes that reverberated throughout its core mission.

Whitman’s “mass of common people” could not have gotten more common than the tramps and hoboes who were routinely recruited by the I.W.W. A product of the vagaries of the seasonal employment situation in the western United States, these migratory workers formed the foundation of the loosely-built Wobbly structure. The wide-ranging experience of itinerant workers developed in the Wobblies a rugged, tolerant, and unconventional lifestyle that shocked the sensibilities of middle class Americans. The Wobblies saw America as a frontier, a break with the stereotypes of the past, a chance for a new kind of life. This same feeling of expansiveness Whitman evokes over and over in his poetry through his catalogs of the American experience and landscape. The wandering Wobbly would find a sympathetic vibration in this poetry. In Specimen Days, Whitman provides “an Undeliver’d Speech” called “The Prairies” in which he sees the American West as the seedbed that will give rise to “a character for your future humanity, broad, patriotic, heroic, and new”; the Wobblies gave rise to a similar mythos in their glorification of the West and the men who roamed its parameters.

In its first years of existence, the I.W.W. increasingly became identified with the hobo culture, a culture composed of men who could be viewed as rebelliously unconnected to conventional norms, and – importantly – men with no wives or families. In the Christian socialist memes of Eugene Debs, Jesus, the ultimate solitary celibate, was often depicted as a hobo, an iconic figure that Wobblies could take to heart. The Wobblies, thus, came to be identified with a culture of rebellious masculinity. The Wobblies sometimes considered wives and families to be one of the links in the chain that connected laborers to the corrupt culture of capitalism. This political organization of male-ness reverberates with Whitman’s ideal state of male comradeship as the basis of a truly democratic society. In the late nineteenth century Horace Traubel and his Whitman Fellowship followers discouraged a homoerotic reading of Whitman’s poetry, but the imagery and language of homosexual desire persisted. Perhaps the migratory, transient, rootless, male Wobbly culture, homosexual or not, was drawn to this language.

The Wobblies believed that working for wages for the profit of the capitalists was a form of slavery. Indeed, they called the working class “wage slaves.” Expending too much energy for the benefit of “the Bosses” seemed irrational to a Wobbly. More importantly, however, in its goal of achieving at least an eight hour work day, the I.W.W. advocated “Bread and Roses” as a motto for the working class – that is, both fair wages for fair work and the leisure time in which to begin to cultivate that part of ourselves which resonates with the arts and our better selves. All of these ideas can be traced to Whitman memes. “How I do love a loafer!” Whitman wrote in 1840, saying that the loafer is “a philosophik [sic] son of indolence.” Whitman wrote that “When I have been in a dreamy, musing mood, I have sometimes amused myself with picturing out a nation of loafers. Only think of it! An entire loafer kingdom! How sweet it sounds!” (112). But the idea of loaferism was also related to the politics of Whitman’s time. The Whigs of New York City in Whitman’s time were associated with capitalist values – the Democrats with whom Whitman identified were associated with loafing, a by-product of the closed labor market of the time. This comingling of the world of art, work, and anti-capitalist attitude was picked up by Wobblies, who visualized an anarchist future in which work and leisure were indistinguishable.

The Wobbly relationship with Walt Whitman was one of mutual satisfaction. In the wage slaves of the I.W.W., Whitman’s poetry finally found the mass audience that he so craved during his lifetime. In appropriating the poetry of an American icon, the Wobblies laid claim to a legitimate elevation of purpose and values in the context of American life. That the poetry subverted many traditional norms gave it additional éclat in the context of the revolutionary Wobbly project. In short, Walt Whitman fulfilled a propaganda function in the I.W.W. at the same time that the I.W.W. provided living, breathing proof of the truth of Whitman’s poetic imaginings. Thus, in a dynamic interplay with the discourses of socialism, anarchism, humanism, and freethought in early twentieth century America, Whitman’s texts helped to shape those forces while at the same time the texts were reshaped by their radical disseminators.

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Elizabeth,

Thanks for this second installment. I’m enjoying the posts.

I wonder how the Wobblies and Whitman, given their links to a kind of “frontier” mentality, reacted to Turner’s Frontier Thesis and the supposed closing of the frontier?

Did you explore Tobias Higbie’s work on the Hobos for your thesis? If so, I wonder how Higbie deals with Whitman in hobo culture. I’m reading Higbie’s new book and will now be on the lookout for Whitman references therein.

Side note: IWW is listed above as “International” instead of the proper “Industrial Workers of the World.”

– TL

Mea culpa for the International/Industrial slip. Of course I know the correct name of the organization!

I use Higbie’s book Indispensable Outcasts: Hobo Workers and Community in the American Midwest, 1880-1930 in my thesis, drawing attention to the way Higbie’s critique of homosexual hobo culture interfaces with both Whitman’s blatant homosexual imagery and his masculine imagery. Higbie writes: “Whereas the dominant culture described laboring men, their rough bachelor culture, the spaces they inhabited, and their very bodies as pathological, broken, and beyond the margins of the community, Wobblies refashioned laborers’ bodies, actions, and places into sites of rebellion that defined their own community” (193). Whitman did this very thing in his poetry, turning the outcast male laborer into a poetic evocation of America itself.

As to your question about Turner’s Frontier Thesis, I can take a running leap and say that Whitman would never admit to any frontier being closed. In both his poetry and philosophical meanderings Whitman is constantly pushing us forward to broader horizons, what he called “a sublime and serious religious Democracy,” the idea of which seems incompatible with a closed frontier mentality. The IWW’s push toward an anarchic future that they called Industrial Democracy resonates closely with Whitman’s vision. For both, America was a work in progress whose frontiers were (or should have been) constantly expanding.