Editor's Note

As part of our #USIH2020 publications, we’re sharing a roundtable on “African-American Intellectuals and Their Critics.” Today’s paper is by Ross English (The New School for Social Research): “Levels of Desire, Levels of Inequality: Black and White Volition and the Intellectual Lineage of the Racial Wealth Gap in the Early Twentieth Century.” Check out our full #USIH2020 conference program and updates here.

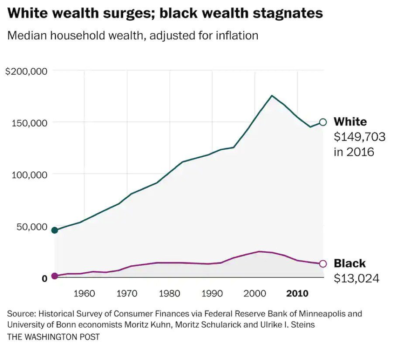

Amidst the publicized social unrest this summer, The Washington Post published an article regarding the role of wealth accumulation in racial communities throughout the country. Its goal was to show how the stagnation of Black wealth specifically provides a connective structure for social upheaval, and the figures remain staggering. “In 1968, a typical middle-class Black household had $6,674 in wealth compared with $70,786 for the typical middle-class white household, according to data from the historical Survey of Consumer Finances that has been adjusted for inflation. In 2016, the typical middle-class Black household had $13,024 in wealth versus $149,703 for the median white household, an even larger gap in percentage terms.”[1]

Amidst the publicized social unrest this summer, The Washington Post published an article regarding the role of wealth accumulation in racial communities throughout the country. Its goal was to show how the stagnation of Black wealth specifically provides a connective structure for social upheaval, and the figures remain staggering. “In 1968, a typical middle-class Black household had $6,674 in wealth compared with $70,786 for the typical middle-class white household, according to data from the historical Survey of Consumer Finances that has been adjusted for inflation. In 2016, the typical middle-class Black household had $13,024 in wealth versus $149,703 for the median white household, an even larger gap in percentage terms.”[1]

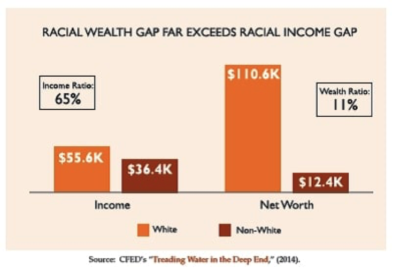

In September of this year, The Federal Reserve published their account of the wealth gap. It describes an extraordinary disparity as Black families retain a 1 to 7 ratio for collective wealth compared to white counterparts.[2] Combined with statistics, the intellectual project of reasoning away this disparity causes a racial shame to arise as white leaders castigate Black communities for their inability to garner wealth. Of most recent note, Jared Kushner—senior advisor and son-in-law to President Trump—invoked a centuries old stereotype by proclaiming that Trump’s policies are made to “help people break out of the problems that they’re complaining about, but he can’t want them to be successful more than they want to be successful.”[3] To him, the impetus again rests upon Black Americans to remove their shroud of inequality by force, desire, or nothing.

Throughout the 20th century, Black intellectuals, the Black public sphere, and white thinkers gazing upon these communities jostled over this separation as they strived to better communities that had little opportunity for advancement. The fascinating, and albeit troubling, intellectual power of the separation between volition and racial wealth equity exhibits a distinct idea in the history of American capitalism. Far from moments of Black liberation from slavery and Jim Crow, similar rhetoric and understandings of wealth are wielded today. Influenced by the work of Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro, Darrick Hamilton, and many other scholars of racial wealth, this piece focuses on the pervasiveness of volition, desire, and income in early twentieth century ideas of wealth accumulation. Focusing on the role of Black scholars in the larger dialogue of racial wealth, I examine the jostling between Black ideas of wealth and the surrounding adaptation of white commentators, ending with the structural concerns of E. Franklin Frazier. I intend to show a glimmer of the continuing rhetoric surrounding racial wealth and the idea of “wanting to be successful,” and connect it to an intellectual lineage throughout the twentieth century.

The ideology of volition and wealth in early 20th century Black communities was largely promoted by Booker T. Washington and those who followed his tutelage. In his 1907 publication The Negro in Business, Washington expounds on the Black experience in numerous areas of labor with chapters dedicated specifically to professions such as hotel workers, factory workers, and so forth. Towards the end of the work, there are future-oriented essays regarding value and growth in Black communities. Washington notes an “upward tendency” of economic stability through ownership of land and tax payment, citing statistics gathered by the Hampton Institute in 1898.[4] The ability for Black communities to enterprise was growing, but Washington includes very little on how these communities are retaining their economic growth. As Washington looked toward the future, he saw a necessity of well-mannered laborers who viewed idleness as disgraceful.[5] The betterment of Black communal value lay largely with their ability to enterprise, and resided little with any attempt to support wealth. Washington followed his book with an essay published in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science in 1910. The issue was dedicated to the involvement and prosperity of Black workers in the Southern United States. Washington’s essay entitled “The Negro’s Part in Southern Development” promotes a similar understanding of Black value as his work from three years prior. After noting that the labor value of Black workers during the end of the slave system was around thirty million dollars in an economy that valued the full capital of Black bodies at one and a half billion dollars, Washington presents labor as the main mechanism for Black advancement.[6] In order to become valued members of society, the laborers must enable themselves with the value of their work and look for further opportunity. Washington’s conflation of opportunity and advancement permeates much of his economic ideology. Wealth, as a concept in Washington’s work, connects directly to income and volition. White thinkers during this time co-opted this ideology to demand further value of Black citizens, thinkers like Andrew Ralston.

Andrew Ralston authored an article in the Journal of Social Forces in 1924 regarding the effects of racial equality on communities. Working as a lawyer during this time, Ralston emphasizes the law and its relationship to racial equality and value. Arguing for the prosperity of segregation, Ralston quotes Booker T. Washington to further his claims regarding Black prosperity and enterprise.[7] Ralston’s rhetoric resembles previous generations, where wealth is freely accessible to whoever strives for it, but Black laborers must be content with their value, rather than attempt to battle against social forces. Ralston notes, “Booker T. Washington aimed at the full Americanizing of his race, and tried to teach the Negro ‘to want more wants.’ He said ‘We should get the family to the point where it will want money to educate its children, to support the minister and the church. Later, we should get this family to the point where it will want to put money in the bank, and perhaps have the experience of placing a mortgage on some property. When this stage of development is reached, there is no difficulty in getting individuals to work six days during the week.”[8] Not only does Ralston co-opt Washington’s ideology regarding Black wealth, he employs it to further his own ideology regarding racial development. The acquisitions of wealth connect directly to larger dialogues about burgeoning wealth in the United States, where those who do not reap benefits of wealth are inherently lacking in some way. Whether it was the normalcy rhetoric of the earlier piece, or Ralston’s exemplification of racial progress, the ability to obtain wealth and harbor it reflects true human ability in many cases. Ralston’s citation of Washington exhibits one reason why dialogues regarding Black wealth are mirrored in different generations, as those who enjoy luxury and the things that wealth provide prove their status as an ideal American citizen, and larger dialogues involving Black wealth frequently question the worth and volition of those without wealth.

Even with the once unfathomable wealth generation of the 1920s, Black scholars during this period wrestled with wealth generation and racial inequality. William Scarbourough, once the president of Wilberforce University and in 1930 employed by the U.S. The Department of Agriculture, looked to the state of Virginia for examples of Black prosperity in farming. Scarborough—a formerly enslaved youth—became one of the first Black scholars of classics in the United States. His piece on Virginia, published four years after his death, casts a vision of Black wealth that promotes optimism and realism simultaneously. From a statistical standpoint, Scarbourough notes that only one out of every seven Black farmers in the country owns their land, and the ownership of land becomes a main asset for wealth accumulation. Their wages provide prosperity unknown by former generations, yet hindered by racialized structures of economic disparity and wealth deterrence. Scarbourough describes these deterrences at length, “the negro farmers’ progress has been achieved in spite of handicaps and in spite of a most undesirable credit system. The majority of these farmers do not make use of the facilities of the farm loan system because of race prejudice, although they may be anxious to do so. They are well aware of the advantages accruing from these loans, but they are unable to enjoy these benefits because they have no one in authority to speak for them.”[9] As Scarborough notes, the opportunity for Black laborers is plentiful in regards to wage earning, but when they attempt to gain wealth through established avenues like credit, they are prohibited. Scarborough continues,

Even with the once unfathomable wealth generation of the 1920s, Black scholars during this period wrestled with wealth generation and racial inequality. William Scarbourough, once the president of Wilberforce University and in 1930 employed by the U.S. The Department of Agriculture, looked to the state of Virginia for examples of Black prosperity in farming. Scarborough—a formerly enslaved youth—became one of the first Black scholars of classics in the United States. His piece on Virginia, published four years after his death, casts a vision of Black wealth that promotes optimism and realism simultaneously. From a statistical standpoint, Scarbourough notes that only one out of every seven Black farmers in the country owns their land, and the ownership of land becomes a main asset for wealth accumulation. Their wages provide prosperity unknown by former generations, yet hindered by racialized structures of economic disparity and wealth deterrence. Scarbourough describes these deterrences at length, “the negro farmers’ progress has been achieved in spite of handicaps and in spite of a most undesirable credit system. The majority of these farmers do not make use of the facilities of the farm loan system because of race prejudice, although they may be anxious to do so. They are well aware of the advantages accruing from these loans, but they are unable to enjoy these benefits because they have no one in authority to speak for them.”[9] As Scarborough notes, the opportunity for Black laborers is plentiful in regards to wage earning, but when they attempt to gain wealth through established avenues like credit, they are prohibited. Scarborough continues,

The human factor enters more largely into accumulation than external circumstances, whether by inheritance or by some other adventurous method. It is the man, after all, who has inner resources who rises and climbs in spite of handicaps. This is seen in all communities where individuals operating in similar movements succeed in surpassing their neighbors in the accumulation of wealth. The laws of success and failure apply to all alike, and it is only the few who achieve eminence in a chosen profession, whether farmer or business man—black or white.[10]

Just as with Ralston and Washington before him, opportunity arises unblemished by the mechanisms of an economic society. Those who live by their labor will be able to overcome obstacles, and it is within the universal human spirit that this ethic arises. Scarborough transitions from a paragraph describing the anxiety surrounding wealth accumulation in Black communities to another that praises the spirit of humanity and expresses the power to overcome racialized hurdles. It begs the question of larger cultural rhetoric surrounding financial well-being, and a broader question regarding the racialized power of these rhetorics, where the overarching white voices of authority direct the intellectual impetus.

The generalized human spirit and the ability to garner wealth with sheer effort became a rallying cry as the Great Depression rose and faded. As Roosevelt’s welfare state calmed with the advice of numerous political groups in the later 1930s and the United States looked to war again, many within the Black community became servants of the military again. While segregation of the military did not end until 1948, The United States deployed nearly 150,000 Black troops. As they returned, one of the central points of dialogue during the 1950s movement for desegregation was civil freedom and underlying economic and social liberation. E. Franklin Frazier—one of the most notable Black scholars during this period and author of one of the seminal texts in race and capitalism literature entitled Black Bourgeoisie—wrote multiple articles during the 50s about economic conditions of desegregation. In 1957, he released his article “The Negro Middle Class and Desegregation.” Expounding on many of his ideas found in Black Bourgeoisie two years prior, Frazier places the Black community within the larger white sphere of sociological concerns, as he thinks one cannot understand the forces of desegregation if they treat Black communities as “atomized subjects.”[11] Frazier’s incisive point about desegregated economic life is that what he calls the “American community” and its power to shape the institutions of the Black communities.[12] More generally, he shows how white communities shape the formation and structure of Black communities. The institutions that provided major service to many Black communities during this time either adhered to white understandings or directly prescribed to white ideas of power and structure. Frazier notices an interesting counterpoint to this: the existence and example of Black-owned businesses that serve only Black communities. Frazier writes, “But how shall we classify the negro economic institutions which are owned by Negroes and cater specifically to needs of the Negro community? I would answer this question by saying that such institutions present an anomaly and that their anomalous position explains their insignificance in the economic life of Negroes as well as in the United States economy.”[13] The power of Black enterprise held little weight in the larger white spheres of economic power. Franklin expounds on this, “Although middle class Negroes have had a longer history in politics, their role has always been one of serving two masters. They have generally attempted to reconcile the interests and demands of the Negro masses with their personal interests and their desire for power which was subject to the final analysis to the white community.”[14] To this point, Frazier emphasizes the pleasing of two masters as a breakup of the larger Black community, as those who enter the Black middle class must answer to white economic structures rather than prioritizing the needs of the Black lower class. The idea of Black wealth must coalesce with the ideas of those who design the wealth structure in The United States, presently and historically the white masters of finance. Implicit in this role of two masters is a corrosive myth regarding the role of enterprise in racial equality. The aforementioned works in this piece point to the manner in which Black communities can save themselves by becoming laborious and enterprising people, giving little attention to the structures that produce wealth and sustain wealth. Frazier accurately names this a myth and writes further, “It was during this period (beginning of the 20th century) that the social myth grew up among Negroes that business enterprise would provide the solution of the Negro’s economic and social problems.”[15] Race-making through business acumen, equality through the labors of their hands and the power of their spirit. Frazier continues,

The Negro had experienced a brief period of high hopes during the Reconstruction period that he would have the rights of other American citizens. But this was succeeded by a period when not only “White supremacy” was restored in the South but as a result of the unresolved class conflict within the white community, the Negro was disenfranchised and lost his right to the same education as the white, and was subjected to a legalized system of racial segregation. He then accepted the myth of economic and social salvation through Negro business which was preached by Negro leaders all over the south. The myth became institutionalized when Booker T. Washington organized the National Negro Business League in 1900. From then on the myth was propagated through the Negro press, from the pulpits of Negro churches, and through pilgrimages throughout the South and to a lesser extent in the North.[16]

According to Frazier, the intellectual lineage of wealth accumulation and salvation of the community began with Booker T. Washington and spread rapidly through different social institutions until it was widely believed and practiced. The conflation of wealth with racial progress materialized in the belief in labor practices and enterprise as the main avenue for racial liberation, and Frazier reiterates the need to view this myth as a blurring of the political and economic realities that truly subjugate Black workers. The Black middle class then becomes a vestige of white power that exhibits prosperity as a universal idea, but in reality climbs only as high as allowed by sociopolitical leaders and economic mechanisms. Frazier’s observation of the desegregation efforts during this decade illuminated the rhetoric of Black wealth as one that provided false optimism for Black communities.

According to Frazier, the intellectual lineage of wealth accumulation and salvation of the community began with Booker T. Washington and spread rapidly through different social institutions until it was widely believed and practiced. The conflation of wealth with racial progress materialized in the belief in labor practices and enterprise as the main avenue for racial liberation, and Frazier reiterates the need to view this myth as a blurring of the political and economic realities that truly subjugate Black workers. The Black middle class then becomes a vestige of white power that exhibits prosperity as a universal idea, but in reality climbs only as high as allowed by sociopolitical leaders and economic mechanisms. Frazier’s observation of the desegregation efforts during this decade illuminated the rhetoric of Black wealth as one that provided false optimism for Black communities.

This myth of financial well-being and wealth accumulation as the pathway for racial liberation began early in the 20th century, and permeated the social dialogue up to the authorship of Frazier’s piece in 1957. Frazier accurately ties the sociopolitical realities of The United States to the myth perpetuated in the Black economic sphere. This rhetoric continued into the neoliberal renaissance of the 60s and beyond, even as many civil rights leaders vowed to combat the economic order in the United States.

[1] Heather Long and Andrew Van Dam, “Analysis | The Black-White Economic Divide Is as Wide as It Was in 1968,” Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/06/04/economic-divide-black-households/.

[2] Neil Bhutta et al., “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm.

[3] Annie Karni, “Kushner, Employing Racist Stereotype, Questions If Black Americans ‘Want to Be Successful,’” The New York Times, October 26, 2020, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/26/us/politics/kushner-black-racist-stereotype.html.

[4] Booker T. Washington, The Negro in Business [Microform] (Boston:Hertel, Jenkins, 1907), 353

[5] Booket T. Washington, The Negro in Business, 356

[6] Booker T. Washington, “The Negro’s Part in Southern Development,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 35, no. 1 (1910): 127

[7] Andrew Ralston, “What Racial Equality Means to the Negro Inter-Racial Cooperation,” Journal of Social Forces, no. 5 (1924): 709

[8] Ralston, “What Racial Equality Means,” 711

[9] William S. Scarborough, “The Negro Farmer’s Progress in Virginia,” Current History (New York); New York 25, no. 3 (December 1, 1926): 386.

[10] William S. Scarborough, “The Negro Farmer’s,” 386.

[11] E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Middle Class and Desegregation,” Social Problems 4, no. 4 (1957): 292

[12] E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Middle Class,” 293

[13] E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Middle Class,” 293

[14] E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Middle Class,” 293

[15] E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Middle Class,” 294

[16] E. Franklin Frazier, “The Negro Middle Class,” 294-295

2 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this really thoughtful piece. Attitudes or rhetorics of wealth among some intellectuals, those “universal” notions (what Scarborough called “laws” of “success and failure” that apply “alike”) had remarkable persistence even as Scarborough’s “external” factors, or structural barriers to equality, took on ever more definite shape into the 20th century, culminating in Frazier’s identification of success rhetoric or Washingtonian self-help rhetoric as a “myth.” So this rhetoric of desire/wealth reflected a kind of optimism (or delusion) despite insuperable obstacles, because if one just looks at the big picture or the aggregate across time, there are pretty profound reasons for pessimism.

This made me think about what Ralph Ellison described in _Invisible Man_ as the “black rite of Horatio Alger” (Ellison uses that line during an amazing, lyrical description of a convocation at the college from which the protagonist ultimately gets expelled.) I’m curious, then, what you make of what is probably a subset or offshoot of your reading of these early twentieth century thinkers, the persistence of stories of this or that successful individual as exemplar or proof/evidence of “making it.” (As in, “Look at what this person did, they made it, so can you, pattern yourself from that,” etc.) It seems like an iconography of achievement or excellence often goes along with this rhetoric of desire. In other words, there are different kinds of evidence at work–the structural and the exemplary. I’m curious what you make of that.

Really enjoyed reading this, especially how you showed the tension between the individualism that’s key to Washington’s ideology with the structural obstacles to Black economic mobility. I have a question, if that’s alright. Did the economic and social changes brought about by the Great Migration have an impact on these debates? The Washingtonian mythology of the Black worker as Southern, rural, and agricultural seems really key to this intellectual history but how did these scholars reckon with real world events which complicated this mythology?