A friend of mine, who is having an especially difficult year, told me a story that he attributed to the fiction of John Irving. This was a story about people taking an unreasonable abundance of caution to avoid an extremely improbable risk of death. Due to an accident too freakish to foresee, the caution taken by the people failed, and everyone died anyway.

Many dislike John Irving’s fiction for its cruel implausibilities, but my friend wanted to push back on that opinion. Implausible things happen all the time, and people are regularly traumatized by them. The comment made sense, coming from this friend, whose recent experience is indeed worthy of a John Irving novel. It was his last remark that struck me. “Everyone needs therapy, more or less.”

The words set in motion a lightning sequence of thoughts. If my friend was right, and everyone got the therapy they required—just to achieve some baseline of health—society would need to find a way to train and employ a great number of therapists. And would that be such a bad thing? I mean therapy not as one more consumer item designed to feed insatiable impulse but therapy broadly understood as any work aimed at the restoration of health. What would our lives be like if more of us worked at jobs that served to heal rather than to wound? What if our economy were organized not for the extraction of value from living systems but for the restoration of their health?

Hardly a beat had passed, and I don’t remember exactly how I responded, except that I used the term, “restorative economics.” It piqued my friend’s interest. He wanted to know what it was and asked for something he might read that would explain it.

It was then I realized that I’d used the term as if it were a thing when I wasn’t really certain that it was. Or if it was a thing—a lesser-known discipline, perhaps, a research field, an item you could look up on Wikipedia—it wasn’t the thing I was referring to. It wasn’t the thing I was referring to because it couldn’t encompass all that was behind what I meant by it. And behind what I meant by it was several years’ worth of reading a variety of texts, some fairly disparate, and the connections between them which are not necessarily gathered under any particular term or in any particular place, except in me, in my own mind, as the reader of those texts.

Readers are nodes in a network of ideas. Readers are essential workers.

The work I did when I got home was to assemble a list, just to understand my process. I’d never used the term before, nor planned to. Why restorative? I stopped at item seven but could have kept going.

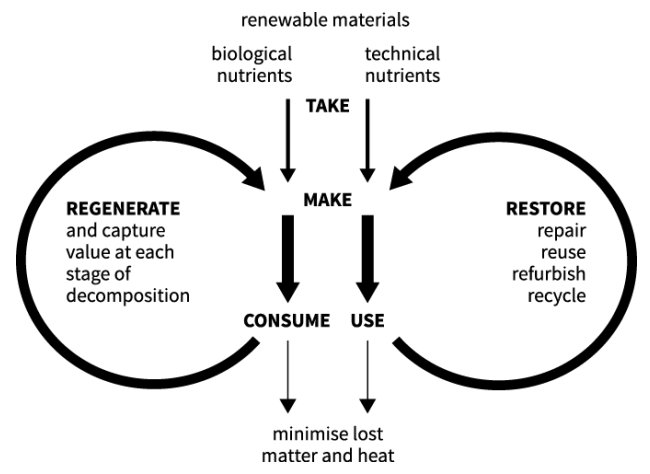

1. Chapter 6 of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (2017). In this chapter, titled “Create to Regenerate,” Raworth describes the concept of a Circular Economy. One illustration she used looks something like a butterfly with two wings, one marked “Regenerate” and the other, “Restore.” Raworth’s book is among many that ask this question: What if the purpose of economic activity was not growth but healing?

Image source: https://www.kateraworth.com/

2. The “restoration story” George Monbiot tells in the first chapter of his book, Out of the Wreckage, A New Politics for an Age of Crisis (2017). “There is something deeply weird about humanity,” Monbiot writes. “We possess an unparalleled sensitivity to the needs of others, a unique level of concern about their welfare, and a peerless ability to create moral norms that generalize and enforce these tendencies” (14). Monbiot represents a strain of postmodernism when he argues that modern ideologies have overshadowed this understanding of what human beings are. That understanding must be restored, Monbiot argues. “Through invoking the two great healing forces–togetherness and belonging–we can rediscover the central facts of our humanity: our altruism and mutual aid” (25).

3. Paul Hawken’s description, in Blessed Unrest (2006), of the international ecological movement. He calls this movement (which barely registers in the US), the “largest social movement in all of human history.” Its participants are “willing to confront despair, power, and incalculable odds in order to restore some semblance of grace, justice, and beauty to this world.” The movement proposes a regime of words beginning with the letter R: “restore, redress, reform, rebuild, recover, reimagine, reconsider” (4).

4. Jason Hickel, author of Less Is More (2020), on what life might be like if the economy was designed for healing rather than growth: “People would be able to work less without any loss to their quality of life, thus producing less unnecessary stuff and therefore generating less pressure for unnecessary consumption. Meanwhile, with more free time people would be able to have fun, enjoy conviviality with loved ones, cooperate with neighbors, care for friends and relatives, cook healthy food, exercise and enjoy nature, thus rendering unnecessary the patterns of consumption that are driven by time scarcity. And opportunities to learn and develop new skills such as music, maintenance, growing food, and crafting furniture would contribute to local self-sufficiency.”

Under such a new framing of economic life, “We would not have to feed our time and energy into the juggernaut of ever-increasing production, consumption and ecological destruction. The economy would produce less as a result, yes – but it would also need much less. It would be smaller and yet nonetheless much more abundant … but public wealth would increase, significantly improving the lives of everyone else.”[1]

When I went back and re-read this passage, I read public wealth as mental health.

5. Daniel Christian Wahl’s project in Regenerative Cultures (2016). Wahl also proposes a regime of R’s: “restorative design,” to restore healthy self-regulation to local ecosystems; “reconciliatory design,” to reintegrate humans into “life’s processes and the united of nature and culture”; and “regenerative design,” to create cultures “capable of continuous learning and transformation in response to, and anticipation of, inevitable change.”[2]

6. The entry for “care” in Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (2015).

It’s first paragraph reads, “Care is the daily action performed by human beings for their welfare and for the welfare of their community. Here, community refers to the ensemble of people within proximity and with which every human being lives, such as the family, friendships or the neighborhood. In these spaces, as well in the society as a whole, an enormous quantity of work is devoted to sustenance, reproduction, and the contentment of human relations. Unpaid work is the term used in feminist economics to account for the free work devoted to such tasks. Feminists have denounced for years the undervaluation of work for bodily and personal care, and the related undervaluation of the subjects delegated to undertake it, i.e. women. Feminists continue to affirm the unique role that care has in the well-being of humans. … [C]are is fundamental in the support the mental, physical and relational integrity of each and every human being.”

7. Restorative justice, a field that explores and promotes legal modes of atonement for crimes, recent and historical. Individual human beings aren’t the only living systems that require restoration. Social groups, too, have suffered damage and deserve reparations.

Right now I’m flashing on the work being done to remove a mountain of asbestos shingles that had been allowed to accumulate in South Dallas and affect the lives and health of the residents of the African American community nearby. It is a classic case of environmental injustice that is finally being addressed and at least partially rectified. When I think of the work of removal being done now, and the years of work that has led to this moment—the reading, the reporting, the organizing and advocating—I think of this as noble work, as therapy, broadly understood.

_____

[1] https://www.jasonhickel.org/blog/2018/10/27/degrowth-a-call-for-radical-abundance

[2] https://designforsustainability.medium.com/sustainability-is-not-enough-we-need-regenerative-cultures-4abb3c78e68b

6 Thoughts on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

On topic: thank you for this post. One of my colleagues, Michael Phillips, was quoted in a recent Washington Post piece on Shingle Mountain: Shingle Mountain: How a pile of toxic pollution was dumped in a community of color.

I saw the DMN story about the work finally getting underway. It’s about time.

Off topic: I bet I know precisely which outlandish John Irving scenario your friend was describing; no spoilers, but it has to be this chapter from The Hotel New Hampshire: “Sorrow Floats.”

That was the first contemporary novel I ever read; everything before that was 19th century fiction, children’s stories, or inspirational works like The Robe or The Silver Chalice. But the summer after 9th grade, I found this John Irving paperback sitting around at my grandmother’s house, left behind by my uncle, and out of sheer boredom I picked it up and read it. I had no idea fiction could be so funny or so weird, and I had read everything by Poe. Changed my life, mostly by making me think I could never write fiction so well (which is doubtless true). But it also opened my eyes to a raunchy, ribald, risqué sort of insouciant good humor about the dirt and grit of human life that I have enjoyed and embraced ever since.

LD, your comment takes me back. I was in high school when The World According to Garp was a phenomenon. I read it and also The Hotel New Hampshire, though it appears you remember that one better than I do. Like you, I was delighted by the humor and the weirdness. Garp opened my mind to gender issues–I’m grateful for that. My memory now is that I became suddenly impatient with Irving’s style, just as suddenly as I had been taken by it. The next book I tried, I couldn’t finish. It’s been a long time. A revisit might be interesting.

Hi Anthony – You are probably well aware of the work of Jem Bendell around the concept, practice and community of what he calls Deep Adaptation, described in a paper by that name in terms of 4 R’s: resilience, relinquishment, restoration and reconciliation:

“In pursuit of a conceptual map of “deep adaptation,” we can conceive of resilience of human societies as the capacity to adapt to changing circumstances so as to survive with valued norms and behaviours. Given that some analysts are concluding that a societal collapse is now likely, inevitable, or already occurring, the question becomes: What are the valued norms and behaviours that human societies will wish to maintain as they seek to survive? That highlights how deep adaptation will involve more than “resilience.” It brings us to a second area of this agenda, which I have named “relinquishment.” It involves people and communities letting go of certain assets, behaviours and beliefs where retaining them could make matters worse. Examples include withdrawing from coastlines, shutting down vulnerable industrial facilities, or giving up expectations for certain types of consumption. The third area can be called “restoration.” It involves people and communities rediscovering attitudes and approaches to life and organisation that our hydrocarbon-fuelled civilisation eroded. Examples include rewilding landscapes, so they provide more ecological benefits and require less management, changing diets back to match the seasons, rediscovering non-electronically powered forms of play, and increased community-level productivity and support. A fourth area for Deep Adaptation is what could be termed “reconciliation.” That is in recognition of how we do not know whether our efforts will make a difference, while we also know that our situations will become more stressful and disruptive, ahead of the ultimate destination for us all. How we reconcile with each other and with the predicament we must now live with will be key to how we avoid creating more harm by acting from suppressed panic.” Bendell, 2019.

Bill, your comment sent me back to a past post, titled Collapse or Transformation, which was about a debate going on between Bendell and Jeremy Lent. In sum: should we be working on our cognitive system for a transformation of the economy (which would entail a transformation of our understanding of ourselves and ecological relations, Lent’s position)? Or should we be working on ways to become more resilient for a societal collapse that is already unfolding (Bendell’s position)? {*https://s-usih.org/2019/04/collapse-or-transformation/*]

That post was from May 2019, over a year ago. Considering the pandemic that has since occurred and that we are still in the midst of, the case that the collapse is unfolding is stronger. Our actions have been mostly reactions, a striving to be resilient under extraordinary conditions. Yet pro-actions aimed at transforming toxic structures have also occurred.

Thanks, Bill. Yes, Bendell should have been added to the list. Great addition.

Anthony – Thanks: I’d forgotten reading your earlier post, “Collapse or Transformation.” Both positions, if that’s it, have a certain belling the cat quality to me.