The Book

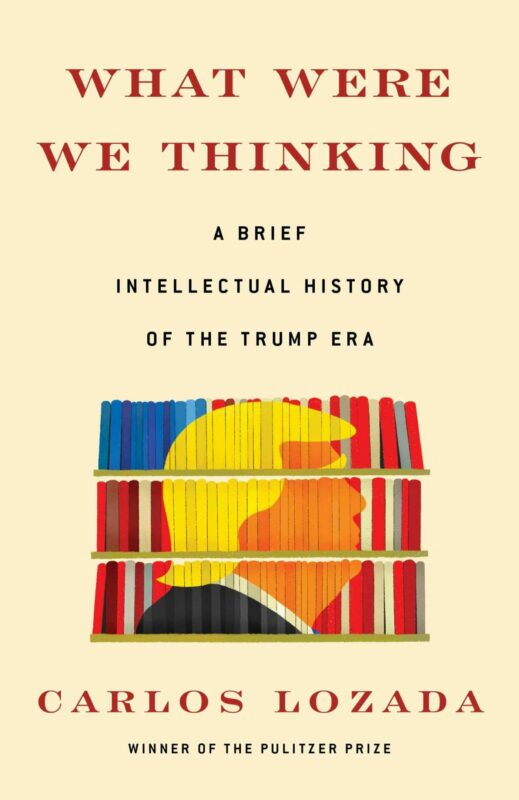

What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2020)

The Author(s)

Carlos Lozada

The last four years have been a cavalcade of debates about identity, race, American culture, and the future of American conservatism. Deep within these arguments is a question of what, exactly, America stands for in the early 21st century. The books written during—and often about—the age of Donald Trump help us to at least struggle towards an answer. Thankfully, Washington Post book review editor Carlos Lozada set out to do just that in his book, What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era. Lozada argues, “The books Americans buy, debate, and prize usually something about how they feel about their prospects, their politics, and their leadership” (5). As intellectual historians, we would certainly agree. But what makes Lozada’s book so intriguing is that, precisely because it was written during the Trump administration—and made no assumptions about the outcome of the 2020 presidential race—it will prove to be valuable for intellectual historians grappling with the American life of the mind from 2016 until 2020.

Throughout the book, Lozada repeatedly mentions how much Donald Trump took up intellectual space in American life. “Every book, it seems can be a Trump book” he mentions early in What Were We Thinking (5). There are, at times, passages that reveal Lozada bordering on intellectual exhaustion with  the topic of Trump—namely, because for him, “The most essential books of the Trump era are scarcely about Trump at all” (7). One does not fully understand the scope of Trump-era literature, however, until you begin to read chapter by chapter. Here, Lozada does a good job of going thematically—from books on the “American heartland” like Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance or Heartland by Kristin Hoganson, to the crisis of racial identity emblematic of such works as Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist or The Once and Future Liberal by Mark Lilla. For all these, and many other books, Lozada tries to be fair to how so many of them were written in the moment, swept up by the need to respond to Donald Trump’s rise and explain his victory in 2016.

the topic of Trump—namely, because for him, “The most essential books of the Trump era are scarcely about Trump at all” (7). One does not fully understand the scope of Trump-era literature, however, until you begin to read chapter by chapter. Here, Lozada does a good job of going thematically—from books on the “American heartland” like Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance or Heartland by Kristin Hoganson, to the crisis of racial identity emblematic of such works as Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist or The Once and Future Liberal by Mark Lilla. For all these, and many other books, Lozada tries to be fair to how so many of them were written in the moment, swept up by the need to respond to Donald Trump’s rise and explain his victory in 2016.

There is a sense, when reading What Were We Thinking, that many of the topics covered in these books will not simply disappear with Donald Trump being a one-term president. This is especially true on the chapter about modern conservatism, where Lozada argues the movement’s writers on Trump can be roughly divided into three categories: “sycophants” who’ve readily embraced Trump; “Never Trump conservatives” who have steadfastly refused to acknowledge Trump as a “true” conservative; and “pro-Trump conservative intellectuals” who want to design a fully-fledged ideology that can survive beyond Trump. Lozada argues, “It is pointless, even dangerous, to avoid or reimagine Trump. But it is vital to look beyond him” (56). In that vein, Lozada’s chapter on books about conservatism in the age of Trump are a reminder of the broader historiographical debates about the rise of the modern Right. That debate has included arguments over the importance of race, economics, gender, and foreign policy to the crafting of a conservative coalition that dominated national politics from 1968 until the early 21st century, but now finds itself at a crossroads.

A similar analysis can be made about the chapter on race and identity, which includes many of the books written on identity in recent years. Lozada cautions us, however, to take too much from books—such as Lilla’s The Once and Future Liberal or Francis Fukuyama’s Identity—when, in his words, “The problem is that America has always lived in the age of identity, with a single category overpowering the rest” (134). This is a reference to the explosion of books on “whiteness,” including of course Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility. Above all, though, there is a concern throughout Lozada’s work that the books directly about Trump do not, in fact, work hard enough to explain both he and the nation in which he became president. “To gaze upon the landscape of identity politics and conclude that this is why Trump won (emphasize his)—that overzealous left-wing activism backfired and gave us the birther lie and Charlottesville and the Muslim ban and so much more ugliness—is to grant identity politics both too much power and not enough,” Lozada argues (141).

Perhaps, then, it becomes necessary for intellectual historians to not see this era as an aberration, or as one that reveals a dark underbelly of American life. We should treat it as we would any other era: one filled with remarkable intellectual and cultural contradictions and illustrated by the heated debates of the era. To Lozada’s credit, he also crafts a reading list of his favorite works during the Trump era, including works by historians Greg Grandin (The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America) and Carol Anderson (No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying our Democracy). Ultimately, What We Were Thinking is an important first book for any intellectual historian seeking to make sense of the Age of Trump. Of course, that era should not be divorced from the Age of Obama, which also sparked the writing of numerous works. And who knows what the upcoming “Age of Biden” holds for the nation’s collective mind?

It may behoove us to get away from naming eras after presidents, to remember that intellectual waves are influenced by numerous factors—only one of which is politics. The early 21st century’s fractures over race, politics, identity, and culture seem to mutate under every national leader. The American mind escapes easy explanation. But intellectual historians of the United States will continue to do our best to understand the thoughts that animate national discourse. Certainly, we will have our work cut out for us with the “Age of Trump.”

About the Reviewer

Robert Greene II is an Assistant Professor of History at Claflin University, as well as blogger and Book Reviews editor for the Society of U.S. Intellectual Historians. Dr. Greene has also been published in The Washington Post, The Nation, Jacobin, In These Times, Oxford American, and other publications.

One Thought on this Post

S-USIH Comment Policy

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.

Thanks for this review, Robert! Glad a review made it to our pages. And, having read the book, I generally agree with your assessment here–a valuable starting point for those exploring this presidency. -TL