Editor's Note

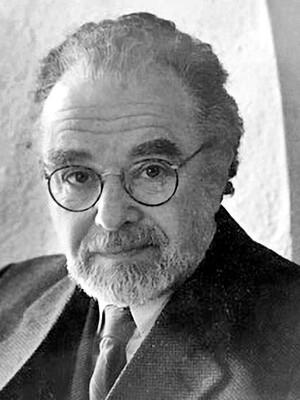

This is one of a series of guest posts we are running at the USIH blog this week to reflect on the scholarly legacy of Alan Trachtenberg, a Yale professor and pioneering thinker in the field of American Studies. Trachtenberg passed away on August 18 at the age of 88.

“But what do we mean by ‘American culture as a whole?’ We all use that easy expression, but can we say what it means? Let me remark that I, too, have suspicions about that word ‘coherence’. I’m very much in favour of disruptions and fractures that challenge all the given and established coherences of what is called ‘America’. Coherence and symmetry ring too much of tyranny and imperial power for my taste. But it’s not just for the sake of re-forming a new coherence that disruption is necessary. It may sound trite to say so but history is a discontinuous process, it moves by leaps and jolts, by cutting and slicing.” — Alan Trachtenberg[1]

Alan Trachtenberg / Yale News Service

Among Trachtenberg’s greatest contributions to scholarship was undoubtedly his advocacy for the use of photographs as a form of historical evidence. His earliest work, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans, a study of American Photography from 1839 to 1938, encouraged scholars to “read” images as historical artifacts and thus broadened what was possible in historical scholarship. It was not sufficient to simply explore the content of the photographs within one’s argument; rather, Trachtenberg suggested that the techniques and processes of photography could lend themselves to analyses of culture and cultural production writ broadly. As scholars look at the wealth of sources made available to them–either in person, through mass digitization, or via born-digital materials–they owe a debt to Trachtenberg who embraced the power of image analysis as evidence to base an argument.

It is perhaps now that his intellectual contributions have never been more prescient. He eloquently linked photographic evidence to sources drawn from social history, labor history, business history, and cultural history—a form of scholarly interdisciplinarity that reflected a broader view of American life than singular methodological exploration. Trachtenberg asked us to take seriously and interrogate the cultural, social, and political worlds that images reflected, circulated, and built. With the growth of mass media, particularly digital media, the importance of images whether still or moving as part of the historical record cannot be denied. Digitization and associated interdisciplinary methods that merge computational vision with humanistic analysis are increasing access to historical photos and their metadata and opening up new areas of study. While computer vision algorithms enable formal analysis at scale, it is the interpretative capabilities of humanities questions that expand our understanding of the past. Network analysis, which models relationships between elements within the context of their creation, offers new ways of visualizing how images circulate. We can not only view the original image but we can model it within its geographical, ontological, and categorical frames as Tractenberg demonstrated.

Take for example, Tractenberg’s reading of the famed FSA-OWI photographs and the archival organization at the Library of Congress. In Documenting America: 1935-1943

Trachtenberg reminds us that the way we organize, classify, and access images shapes the histories that we tell. While analog organizational structures are often limited via archival protocols of item, folder, box, collection and the like, the turn towards digital forms of organization opens up the ability to not only recreate analog archival structures but to also remix those contents into new narrative and structural forms. Scholars can create their own organizational structures including digital collections and exhibits. They can also develop projects like Photogrammar, a web-based platform for organizing, searching, and visualizing the 170,000 photographs from 1935 to 1945 created by the United States Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information (FSA-OWI). With Photogrammar, colleagues Laura Wexler (Yale University), Lauren Tilton, and Taylor Arnold, have drawn directly on and extended Trachtenberg’s interdisciplinary analysis toward a dynamic interface. Users can map, visualize, and explore images and their metadata. It is possible to trace the entire catalog of a photographer, explore all photographs taken in a given location regardless of who took the photo, and recreate now dis-articulated photo strips which provide the images in the order in which they were taken. Through Photogrammer, users can contextualize a single photo within the entire FSA project which allows them to better understand how the project crafted particular narratives of American life in the period between the Great Depression and World War II. Projects like Photogrammar return us to the provocation Trachtenberg offered to American Studies. What does an image mean and how does it shape our understanding of the past?

At a moment when scholarly researchers often experience images unmoored from their original and archival contexts through a world of digital databases, Google searches, and Twitter algorithms, the images that we see as scholars are mediated through technologies that shape what, how, and when we see an image. These views can be as regulated as archival ones are; but they can also be highly customized and lend themselves to overrepresentation of certain images and underrepresentation of others. The need to interrogate, understand, and even disrupt how we see images is a part of Trachtenberg’s enduring legacy that becomes more important as researchers are distanced from physical archives. All the while never forgetting the power of close reading one to two images and the worlds they could reveal.

It is not only the image that we are encouraged to explore through Trachtenberg’s work. It is also the topics (one might even say keywords) he explored that resonate loudly today: capitalism, corporatism, empire, immigration, spectacle, and the public sphere. The underlying questions that motivated all of his scholarship– such as who is an American and how did America get here– remain vital to scholarly and popular audiences. Woven throughout The Incorporation of America and his 2004 work, Shades of Hiawatha: Staging Indians, Making Americans, 1880-1930, was an interest in how race and identity were expressed in the dual projects of American capitalism and American expansion. Readers learned that literary works by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville, and others were rife with racial tropes that supported the project of American nationalism. Writers, artists, and politicians all sought to engage with questions of American nationalism; so too did Natives and immigrants who reckoned with their own place within the national fabric. Readers were reminded of the brilliant work of scholars like Philip Deloria, Shari Huhndorf, Susan Schekel, Robert Berkhofer, and others who deeply interrogated how white Americans performed identities that relied on opposition: opposition to Native sovereignty, opposition to immigrant groups who were displacing earlier waves of migrants, and opposition to change both politically and socially. The analysis of Edward Curtis’ photography has had a particularly long-lasting import on those who explore Native representation. Trachtenberg argued that Curtis’ images served to educate immigrants on “the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them,’ whites and redskins. It was to reaffirm whiteness as the color of the United States.”[2] This analysis joined the work of Martha Sandweiss (Print the Legend) and Tamara Northern (To Image and To See) that would influence later scholarship that explored Native agency[3], the transnational elements of Native culture[4], and the way photographic images contributed to Native mascotry[5].

The pages of his work provide a master class in interdisciplinary evidentiary interpretation and argumentation that would shape, and continue to influence, not only the field of American Studies but also the historical discipline more generally. His experimentation and openness to interdisciplinary inquiry accelerated the shift from the myth and symbol school to the cultural turn in American Studies while trailblazing cultural history. As we honor his work and recognize his passing, perhaps his most enduring legacy will be the continuing citations of his work and how it models for us the possibilities that are available when we experiment with new methods and approaches. His work continues to offer foundations on which we pose and answer questions about “American” culture(s) in the 20th and 21st century.

“To exemplify the interdisciplinary as such was not part of [The Incorporation of America’s] agenda,” wrote Alan Trachtenberg in his 2003 reflection on the impact of his 1982 text. The agenda was “only to tell as complete of a story as [he] could about a critical passage in the history of US society and culture.[6]

As we reflect on the impact of Alan Trachtenberg’s half century of scholarship, we are struck that his reflection on a single work, The Incorporation of America, stands as a larger prism through which the entirety of his scholarly contributions should be read. Students today may take interdisciplinarity in both sources and methods for granted in their classrooms and research. Those with a longer gaze understand that Trachtenberg’s integration of methods from art, social history, labor history, business history, and other disciplines laid the groundwork for today’s expectation that American Studies is inherently an interdisciplinary endeavor. Trachtenberg’s work remains on reading lists and in circulation not only because it served as a provocation for many scholars’ work— including our own—but also because his work illustrates the powerful ways of reading images and performances as cultural products. For decades, he has been asking us to see in new ways; we can only encourage scholars to continue seeing the possibilities within American Studies.

Jennifer Guiliano is a white academic living and working on the lands of the Myaamia/Miami, Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, Wea, and Shawnee peoples. She currently holds a position as Associate Professor in the Department of History and affiliated faculty in both Native American and Indigenous Studies and American Studies at IUPUI in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Lauren Tilton is Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities in the Department of Rhetoric & Communication Studies and Research Fellow in the Digital Scholarship Lab (DSL) at the University of Richmond. Her research focuses on 20th and 21st century U.S. visual culture.

___________________________________

[1] Paul Giles, “Alan Trachtenberg, in Conversation with Paul Giles,” Comparative American Studies 6 no.1 ( (2008): 5-11, DOI: 10.1179/147757008X267204

[2] Alan Trachtenberg, Shades of Hiawatha: Staging Indians, Making Americans: 1880-1930, 1st pbk. ed (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005), 196.

[3] Shamoon Zamir, Alexander B. Upshaw, and Edward S. Curtis, “Native Agency and the Making of ‘The North American Indian’: Alexander B. Upshaw and Edward S. Curtis,” American Indian Quarterly 31, no. 4 (2007): 613–53.

[4] Shari M. Huhndorf, Mapping the Americas: The Transnational Politics of Contemporary Native Culture (Cornell University Press, 2011).

[5] Jennifer Guiliano, Indian Spectacle: College Mascots and the Anxiety of Modern America

[6] Alan Trachtenberg, “‘The Incorporation of America’ Today,” American Literary History 15, no. 4 (2003): 759–64.

0